I recently posted detailed information on the area south of Jerusalem, today called East Talpiot, where the so-called “Jesus family tomb” was discovered in 1981, with maps and diagrams of the modern streets and apartments in the area, see “Where are the Talpiot Tombs Located?” Apparently, judging from the thousands of page views, readers found these posts of great interest and quite a few have written to tell me they either have visited or intend to visit the area when in Jerusalem.

When our book The Jesus Discovery was published in February 2012 we suggested there might be a connection between the ancient “rich man’s estate” in East Talpiot and the mysterious character, otherwise unknown character, Joseph of Arimathea, who is mentioned in all four of the New Testament gospels. Some have objected that we were going way beyond the evidence since no ossuary inscribed “Joseph of Arimathea” had been discovered in either of the two tombs. Of course we are not certain an ossuary belonging to him would have that particular toponymic designation, but there is some interesting new topographical evidence that might support our hypothesis.

First, for new readers, I have argued that our gospel accounts imply not one but two burial sites for Jesus–one temporary, the other permanent, see my posts “Reading Mark and John: Naming the Names and Jesus’ First Burial,” and “What Really Happened Easter Morning?–The Mystery Solved.”

What some have not realized is that the Talpiot “Jesus family” tomb is located on what appears to be a 1st century family estate with not one but at least three ancient cave tombs clustered together. The one under the condominium building was the site of our robotic camera exploration in 2010 and you can read our preliminary report on that tomb here. In the 1980s, when the construction companies were tearing up the area to build residential dwellings, mostly apartments and condominiums, the Garden and Patio tombs were not the only ones uncovered. Just to the north of the “Jesus” tomb, less than sixty feet away, was another tomb that had been blasted away almost entirely. All that was left was one of its inside walls with the partial remains of the niches still visible. None of its contents could be studied or evaluated but it likely belonged to the same farm or agricultural estate. Nearby were the remains of a plastered ritual bath called a mikveh and in the immediate vicinity there was also an ancient olive press and various water cisterns. Joseph Gath, who surveyed the entire area around the tombs, concluded that these installations belonged to a large farm or wealthy estate and most likely these three tombs belonged to the owner, clustered so closely together.[i]

A highlight of our continued investigation was the subsequent use electrical resistivity tomography (ERT) or electrical resistivity imaging (ERI) a geophysical technique for imaging sub-surface structures from electrical measurements made at the surface, or by electrodes in one or more boreholes. We thank Richard Freund, director of the Maurice Greenberg Center for Judaic Studies at the University of Hartford for facilitating this marvelous project. You can read more about Prof. Freund’s award winning and pioneering work here. The initial tomography testing has yielded some very promising results in defining the parameters of this ancient estate. You can watch this entertaining video on Youtube of our investigation of the area and get a good sense of the lay of the land–even without making a trip to Jerusalem, complete with Reggae music!

But why Joseph of Arimathea? And is this idea so far fetched and speculative after all? The only person we know of who had charge of Jesus’ burial was Joseph of Arimathea–with the backing of the Roman and Jewish authorities. Some have argued that “Arimathea” refers to a nearby town, but the name literally means “Two Hills,” and it is entirely possible it is a geographical location–maybe even the name of an estate in Jerusalem.

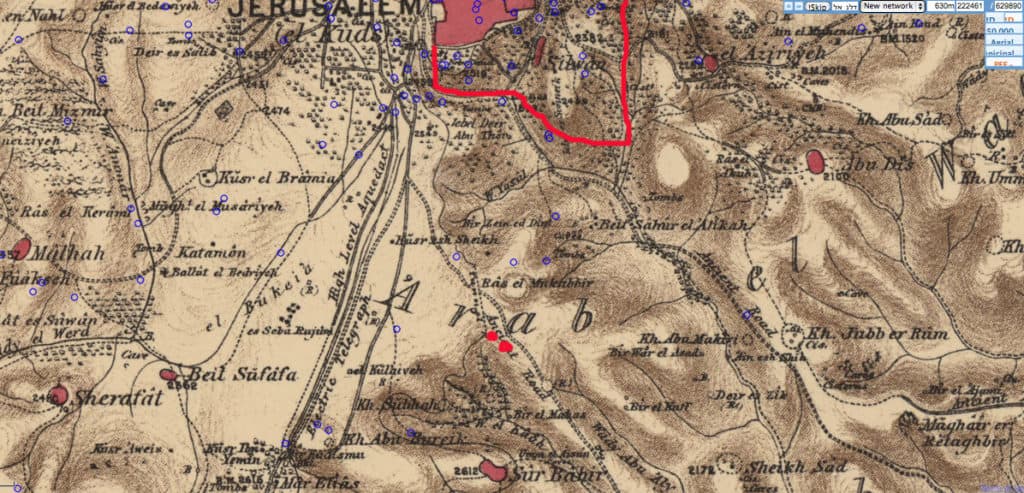

Here you can see the British topography map done in the last century before all the buildings and modern roads existed. It shows more clearly the features of the area just south of the walls of ancient city of Jerusalem, shown here in red outlines. The two Talpiot tombs that we have explored are marked as red dots.

Few outside of Jerusalem had ever heard of the district of East Talpiot, two miles south of the Old City of Jerusalem, until the news stories regarding the “Jesus” tomb made headline news around the world in March, 2007. According to the gospel of John the tomb in which Jesus was initially placed in haste, until full burial rites could be performed after the Passover, just happened to be near the place of his crucifixion (John 19:41). Millions of Christians visit Jerusalem each year and they are invariably taken either to the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in the Christian quarter of the Old City, or an alternative site, just north of the city, more popular with evangelical Protestants, called “Gordon’s Calvary.” They come to either spot to view the place that they believe Jesus was crucified, buried, and raised from the dead on that first Easter morning. The crowded rows of condos and apartments that make up the various neighborhoods of East Talpiot is understandably not on the Christian tour agenda.

In the time of Jesus things were of course quite different. The hills south of Jerusalem, down toward Bethlehem, were relatively sparsely populated with private lands devoted to agriculture and livestock. The neighborhood where the Garden and Patio tombs are located is called Armon HaNatziv. It is just off a high ridge called the Promenade that provides a spectacular view of Jerusalem to the north and Bethlehem to the south, and still attracts busloads of tourists today. In ancient times there was a main road crisscrossing the area, running southeast, that passed the famous Mar Saba monastery and went down to the Dead Sea, near Qumran, where the Dead Sea Scrolls were found. To the west of the three tombs, just a few hundred yards away, was a spectacular aqueduct that transported water from Tekoa, south of Bethlehem, north to Jerusalem. The area is thick with ancient biblical history. Abraham travelled this route on his way to Mount Moriah as recorded in Genesis 22:1-4. Rachel, wife of Jacob and mother of Joseph and Benjamin, is buried on the road running south to Bethlehem (Genesis 35:16). Just to the south and east of Bethlehem, actually visible from Talpiot tombs, is the magnificent Herodium, the tomb of Herod the Great, the Roman appointed “King of the Jews.” See my post “That Other King of the Jews.”

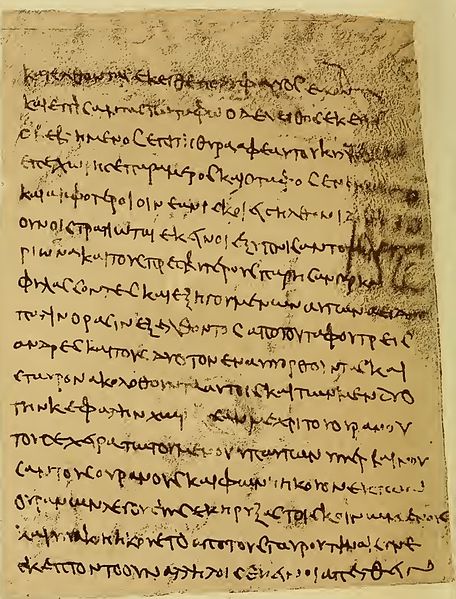

Ancient historians work with evidence, archaeological and textual, seeking to discern if there is any fit between what we read in our texts, in this case the Gospel accounts of Jesus’ death, and what is found in excavations. They often construct working hypotheses to test whether the various types of evidence fit together and what the alternative interpretations might be.

In considering whether the Garden tomb might indeed be the tomb of Jesus of Nazareth and his immediate family a key historical question arises. Who was it that was reported to be responsible for Jesus’ burial according to the New Testament gospels? The name that immediately leaps off the pages is of course none other than Joseph of Arimathea, who had enough wealth and influence to go directly to Pontius Pilate, the Roman prefect of Judea, to request the burial rights for Jesus’ body. Such a task would normally fall to the immediate family, or to the closest disciples of a teacher such as Jesus. For example, we learn in the gospel of Mark that when Herod Antipas beheaded John the Baptizer, his disciples were allowed to come and take his severed body and bury it in a tomb (Mark 6:29). In all four of our gospels, Joseph of Arimathea appears mysteriously out of nowhere, just after the crucifixion. He gets permission from Pilate to remove Jesus’ corpse from the cross and carry out the Jewish burial rites for Jesus (Mark 15:43-47).[ii] We never hear of him again. He is said to be a member of the “council,” or Sanhedrin, the indigenous Jewish judicial body responsible for Jewish affairs, as well as a sympathizer with Jesus and his movement. If one wants to understand what happened to Jesus’ body after the crucifixion one has to pay careful attention to Joseph of Arimathea. It was he and he alone who had the legal responsibility for Jesus’ proper burial. What most readers of the New Testament have missed is that Joseph of Arimathea initially placed the body of Jesus in a temporary unfinished tomb that just happened to be near the place of crucifixion. It was an emergency measure so that the corpse would not be left exposed overnight, which was forbidden by Jewish law (Deuteronomy 21:23). It was late afternoon Jesus died and the Jewish Passover was beginning at sundown that very evening. Although Jewish tradition required that a body be buried as quickly as possible the full rites could not be carried out before the Passover meal began. The gospel of John explains it best:

Now in the place where he was crucified there was a garden, and in the garden a new tomb where no one had ever been laid. So because of the Jewish day of Preparation, since the tomb was close at hand, they laid Jesus there (John 19:41-42).[iii]

Jesus was temporarily placed in this new tomb, with the entrance blocked up with a stone, to protect his body from exposure and from predators. According to Mark all Joseph had time to do was to quickly wrap the bloodied body in a linen shroud—no washing, no anointing, no traditional Jewish rites of mourning—nothing (Mark 15:46). The women, including Jesus’ mother, his sister, Mary Magdalene his companion, and others, who followed at a distance had every intention of completing the Jewish rites of burial, that involved washing the corpse and anointing it with oil and spices, just as soon as the Sabbath was over (Mark 16:1). Joseph, in asking to take charge of the proper burial of Jesus, clearly had a more permanent arrangement in mind. The most likely scenario is that he planned to provide Jesus, and subsequently his family, with a cave tomb at his own expense, and possibly on his own estate outside Jerusalem. That he was a local resident seems certain based on his membership in the Sanhedrin, and he is the one who would have had the means to provide the family of Jesus, who were from Galilee, with a family cave tomb.

[i]Typed report of Gath dated April 15, 1980 now in the IAA archive files for License 938.

[ii]Compare Matthew 27:57-61, Luke 23:50-56, John 19:38-42.

[iii]Matthew’s assertion that this temporary tomb belonged to Joseph is clearly an interpolation added for theological reasons (Matthew 27:60). It lacks any historical basis or even likelihood. What would be the chances that Joseph, who took charge of Jesus’ burial, just happened to own a tomb right adjacent to the place the Romans used to crucify criminals? A major theme of Matthew’s gospel is to show how Jesus fulfilled prophecies of the Hebrew Bible as the messiah. Here he has in mind Isaiah 53:9 that he interprets as requiring the “suffering servant” to be buried in a rich man’s tomb. None of the other gospels make this claim and John, in explaining the circumstances for the choice of this temporary tomb, flatly contradicts Matthew.

Comments are closed.