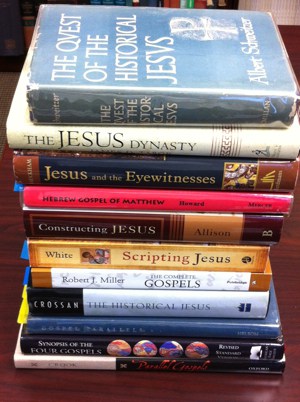

It has become almost axiomatic to assume that any responsible “quest for the historical Jesus” will value the Synoptic gospels–particularly Mark–as primary and more historically reliable in contrast to the gospel of John, which is viewed as secondary, and thus much more theological than historical. [1]The Jesus Seminar lists this as one of its “Seven Pillars” of scholarly wisdom, see Robert Funk, The Five Gospels: What Did Jesus Really Say? The Search for the Authentic Words of Jesus … Continue reading Although there has been a growing recognition of the heavily theological nature of Mark, Matthew, and Luke–including the so-called Q or “Sayings” source–the general result has been a favoring of Mark over John.

![]()

I studied in the 1970s at the University of Chicago with the late Norman Perrin who advanced the recognition of the theological elements of Mark, to a new level. [2]See my tribute to Perrin here. Krister Stendahl (The School of St Matthew 1954), Anthony Saldarini (Matthew’s Jewish-Christian Community 1994), Hans Conzelman (The Theology of St. Luke, 1961) and a host of others have done the same for Matthew and Luke. The result has been the recognition that none of our gospel writers are composing history per se, and all are expressing their individual theologies–particularly their Christology–as a first priority in the ways they cast the Jesus story.

The recognition of the stark differences between the Synoptics and John is implicitly recognized in the early Church. Clement of Alexandria writes that “John, last of all, conscious that the outward facts had been set forth in the Gospels [i.e. Matthew, Mark, and Luke], was urged on by his disciples, and, divinely moved by the Spirit, composed a spiritual Gospel” (Eusebius, Church History 6.14.7). Although there is no doubting that John’s gospel is heavily theological in a more overt way than is obviously apparent in Mark and the Synoptics, it would be incorrect to conclude that it is of no value in contributing to our “quest for the historical Jesus.” In recent years there has been an enormous amount of scholarly work done on John and its contributions to historical Jesus studies–so much so that one might refer to this trend as a kind of “rehabilitation” of the gospel of John. [3]See in particular the work of the Society of Biblical Literature’s ongoing “John-Jesus-History” Group that began in 2002 and is still ongoing.

John is a very complex book with several layers of tradition embedded therein to give us the version we have now. Scholars have identified an earlier “Signs Source” that runs through the whole (1:19-12:50). There is an appended “Epilogue” in chapter 21 that rather strangely continues the story after the clear and definitive ending of 20:30-31. There is mysterious role of the unnamed “disciple whom Jesus loves,”whom I have identified as James the brother of Jesus, who appears to be named as an eyewitness source in John 21:24. Chapters 6-10 and 14-17 are quite literally filled, with page after page, of extended “red letter” Dialogues and Monologues attributed to Jesus. This material is starkly different in both style and content in contrast to the teachings and sayings of Jesus in the Synoptics. In the gospel of John Jesus never speaks in parables, offers short maxims or sayings, or focuses his work around exorcisms and preaching the “Kingdom of God” as in the Synoptics. Jimmy Dunn has convincingly argued that the style and vocabulary of Jesus’ speaking in John is that of the writer of the letter of 1 John–not of the historical Jesus. [4]See his contrasting breakdown and analysis in James D. G. Dunn, The Evidence for Jesus (Philadelphia, Westminster Press, 1989): 30-45.

What I have concluded over the past few decades in my own work on the historical Jesus is that John is an invaluable resource, especially in matters of chronology and geography. For a start, see the simple handout I use in my classes on “Narrative Movement in the Gospel of John.” ((See, for example, my article “Wadi el-Yabis and the Elijah “Wadi Cherith” traditions in Relationship to John and Jesus in the Gospel of John,” and James Strange, “John and the Geography of Palestine.” I have also found that the material John uniquely provides often correlates in remarkable ways with recent archaeological evidence in both Jerusalem and the Galilee. In my own work I have used John exclusively or primarily in several areas of investigation including the Suba cave at Ein Kerem, “A Jesus Hideout in Jordan,” “The Last Supper and Passover,” “Locating Golgotha,” the “Burial of Jesus,” and the judgment seat of Pontius Pilate–to name a few.

What I propose to do in future posts is to offer a series of correlations between the basic materials found in John and the text of Mark on a wide variety of topics. Stay tuned for some interesting and new insights.

Comments are closed.