Most of us who do academic work on Jesus and early Christianity often refer to what we do as “Christian Origins” or “Christian Beginnings.” It is more specific than just Bible or the history of ancient Mediterranean religions.

The operating question seems to be how to account for Jesus himself–i.e., “What kind of a Jew was Jesus?”, but more to the point, why is it that the movement he began flourished, thrived, and developed, into something recognizably different from other forms of “Judaism,” to the point that it could finally get its own label, or set of labels (Nazarene, Ebionite, Christian, et al.). The challenge is to try and figure out how much of what becomes uniquely “Christian” might have its roots in Jesus himself, and how much was developed along the way, with little to no connection to anything he would have advocated or recognized. Debates in the field about “early” and “late” Christology turn on this issue and determining what might have come from Jesus and what was “in the air” and part of the development of any Jewish movement of the time in the Hellenistic Roman world has received so much attention that it is hard to keep up with it all.

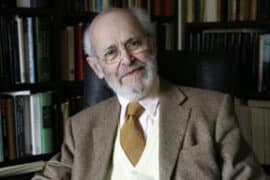

Geza Vermes (1924-2013), well known for his books, Jesus the Jew (1981) and The Religion of Jesus the Jew (1993), bites off the whole chunk in his one of his last books, Christian Beginnings: From Nazareth to Nicaea, AD 30-325 as his title testifies.

Rowan Williams has an amazingly insightful review of Vermes’s new book in the Guardian, here. He sees this as a “beautiful and magisterial” book, but one that leaves unsolved some of the major puzzles that we all continue to struggle with, namely, what are the elements that cause “the alchemical change in Christianity that will make it unrecognisable to its founder.” Most of us assume the basic alteration is a matter of someone (using Paul and his pals), turning the faith that Jesus held into a faith about himself. I find myself leaning in this direction as well, as evidenced in my book, The Jesus Dynasty, as well as, Paul and Jesus. But there is always the possibility, as Morton Smith avowed (Jesus the Magician), that the real and fertile seeds for most of what became Christian go back to Jesus himself–including the central rites of baptismal initiation and participatory meals for the dead. This, of course, is the modified position of orthodox, fundamentalist and evangelical forms of Christian faith–though they would eschew Smith’s reconstruction thereof. All that Christianity became, from Jesus to Paul to Nicea, was one great unfolding of God’s New Testament revelation with all its implications finally realized in history and in the Great Church.

The latest expression of my view is my recently republished take on Paul, in which I come down solidly on the side Paul being the central figure in the great transformation, with lots of new evidence: Paul’s Ascent to Paradise: The Apostolic Message and Mission of Paul in the light of His Mystical Experiences, available on Amazon worldwide in both Kindle and print editions.

Comments are closed.