I am sometimes asked, “what is your greatest discovery or insight in the world of biblical archaeology?” I have been involved in or stumbled upon quite a few things over the past thirty years, including the “Tomb of the Shroud,” with Shimon Gibson, and our ground-breaking DNA and ancient disease studies, see here and here, as well as my findings at Wadi-El Yabis–which I have called a Jesus hideout in Jordan. But this one is surely in the top five or ten, resulting in a peer-reviewed publication that has had a significant influence in the field of Qumran/Dead Sea Scroll studies. I include the entire story here, as well as a PDF of the publication.

On the other days they dig a small pit, a foot deep, with the paddle of the sort given them when they are first admitted among them; and covering themselves round with their garment, that they may not affront the rays of God, they ease themselves into that pit.

Josephus War 2. 148

This post deals with efforts to locate the latrines or toilets outside the ancient settlement of Qumran, the site associated with the caves in which the Dead Sea Scrolls were found. I am convinced we did indeed locate the area so used but what a surprise awaited us that we could have never imagined. I suppose one could call this the “high cost of being holy.”

In considering this specific topic I want to also explore the larger issue of the complex and shifting dynamics of comparing texts with texts, texts with “sites,” and sites with themselves, but without texts. In other words, when does a text tell us about a site, or a site about a text, and how do they work together, or separately. Read on and I will explain more.

I use the term “sites” loosely to refer to the material or archaeological evidence that may or may not be related to a given text from antiquity. I see this as an extension of Jonathan Z. Smith’s interest and fascination with “comparisons” so evident in much of his work over the past three decades. But more particularly I have in mind the Louis H. Jordan Lectures in Comparative Religion, delivered at the University of London in 1988, subsequently published as Divine Drudgery.[1] Fascinated by the “thick dossier of the history of the enterprise,” i.e., the comparison of “Christianities” and the religions of Late Antiquity, Smith undertakes what he calls “archaeological work in the learned literature” in order to highlight both theoretical and methodological issues. His operative question is what is “at stake” in the various comparative proposals? I am convinced that some of the same dynamics Smith finds operating in the development of the study of “Christian Origins,” namely Roman Catholic and Protestant apologetics and presuppositions, have been present from the beginning in considering the textual corpus known as the “Dead Sea Scrolls,” and in interpreting the physical site of the adjacent ruins of Qumran, as well as in the combining of the two—that is, texts and site. I want to expand a bit the comparisons of “words,” “stories,” and “settings” beyond their purely “textual” levels, and explore the methods of bringing in non-textual evidence, that is, evidence of “place.” In that sense I find Smith’s metaphor of the “archaeological” more than intriguing, and in this paper, with spade in hand (or perhaps I might say with “paddle” in hand!), I want to explore how the proverbial “mute stones” speak, or remain silent, in the presence of texts, and the ways in which the texts inform “place,” and “place” might enlighten the texts.

The inclusion of selected archaeological evidence related Roman Palestine, and more particularly the Galilee under Herod Antipas, has added an interesting new dimension to the methodologically depleted study of “Christian origins.” Indeed, Crossan and Reed, in the most ambitious synthesis to date, attempt to “excavate” both texts and sites in their reconstruction of what we can know of Jesus and his earliest followers.[2] In the end, unfortunately, their use of “place” ends up being as arbitrary and as ambiguous as that of the textual layers of the Jesus “traditions.” What is lacking is a “fit,” or a series of case studies or “checks” through which one might actually achieve some meaningful results in the comparative correlation of text and place.

The Site of Qumran

Qumran is arguably the one of the most famous and controversial archaeological sites in the Mediterranean world. It has attracted millions of tourists, especially since the 1970s, having become, along with Masada, a “must see” site for any Holy Land tour. Yet both its fame and its controversy arise because of the discovery of ancient texts—the Dead Sea Scrolls—in caves adjacent to and near the site. It is unlikely that Qumran would have attracted much attention on its own, were it not for its possible connection to the community that wrote the Scrolls.

In a passing remark, reporting on his excavation of Cave 1 with Harding in 1949, Fr. Roland de Vaux concluded that their initial survey of the site of Khirbet Qumran showed no archaeological connection between the settlement and the cave with its manuscripts. For centuries the site of khirbet Qumran had remained largely undisturbed though a few ruins were visible above the ground. In the mid-19th century one begins to see reports from various travelers and surveyors of the site,[3] particularly de Saulcy (1850),[4] Rey (1858),[5] Conder and Tyrwhitt-Drake (1873)[6] and Clermont-Ganneau (1873).[7] De Saulcy, a Flemish explorer, was convinced he had found the ruins of the biblical Gomorrah (Gen 19). Clermont-Ganneau rejected this identification. He records that the ruins were “insignificant” but took special note of the cemetery, and even opened one of the tombs, concluding them to be a mystery, neither Muslim, Jewish, nor Christian, due to their odd north-south orientation and their lack of artifacts or emblems. In the 20th century the reports continued: Masterman of the PEF (1903);[8] Abel, who did a cruise of the Dead Sea, stopping at Ain Feshkha and Qumran (1909),[9] Dalman (1914),[10] Noth (1938),[11] Baramki (1940),[12] and Husseini (1946).[13] One recent but largely unexplored source, to my knowledge, are the records and diaries of some of the early Zionist pioneers and travelers who took an interest in the Dead Sea area, from Jericho to Masada, such as David Horowtiz (1926).[14] Typically these observers made special note of the tower, the extensive boundary walls, the reservoirs and cisterns, and the aqueduct. Noth ventured that the ruins were the City of Salt mentioned in Joshua 15:62. Dalman thought it to be a Roman fortification of some type. What seemed to stump everyone, however, was the extensive cemetery of at least 1000 graves, with their odd, mostly north-south, orientation.

De Vaux’s subsequent five seasons of excavating the site (1951-56), coupled with the discovery of caves 4-10 (1952-55) in the very “backyard” of the settlement, seems to have forged an inseparable link between the scrolls and Qumran. Such identification was further cemented by the rapid publication of the initial sectarian texts from cave 1 (1948-49 Sukenik; 1950-51 ASOR), and an analysis of the classical texts from antiquity that describe the Essenes (primarily Pliny, Philo, Josephus). Based on Pliny the Elder’s (23-79 C.E.) description, that the Essenes lived north of Ein Gedi and Masada (their reading of the disputed infra hos), and Dio Cocceianus’ reference to a prosperous city “not far from Sodom” (which many in ancient times placed at the north end of the Dead Sea), they settled on the ruins of Qumran as a likely possibility. What intrigued them most was the large cemetery of over 1000 oddly oriented graves, signaling to even the casual observer two related concepts: “sectarian” and “community.” The two made a surface examination of the site and opened two tombs. They returned in November, 1951 and subsequently carried out five seasons of excavations, identifying 144 schematic loci and opening 43 of the graves. The main cemetery seemed to contain only males, but in the north, south, and eastern extensions tombs with five females and four children were also found, but apparently oriented east-west. Three of the five women’s tombs had some poor ornaments.

What de Vaux uncovered at Qumran was rather remarkable by any measure. He discovered three main phases of sectarian occupation, which he labeled as periods Ia/b, II, and III), running from mid-second century BCE down to the 1stRevolt. He had complied a composite list of “Essene” characteristics from the classical sources, primarily Pliny, Philo, and Josephus. They were a celibate or mostly celibate group, separatist in their view of society, shunning wealth and property and sharing a single treasury and a common table. They practiced rites of ritual cleansing, and ritual meals and enforced a strict and high standard of community conduct. Although they apparently opposed the sacrificial system at the Jerusalem Temple, it was not clear as to whether they shunned sacrifices totally, nor was it completely clear as to whether they were strictly pacifists in their attitudes toward outside enemies.

Although de Vaux was later criticized for interpreting his evidence in the light of a pre-determined “Essene hypothesis,” the correspondence he found between the material site and what he assumed as the social and religious life of the community, was rather impressive.

After all, the main cemetery did appear to be predominantly male, and the orientation of the corpses was not toward Jerusalem. Their careful interment appeared to reflect the solemn dedication of a separatist community. Locus 77 could have served as an assembly room or dining hall, and adjacent thereto, in loci 86 and 89 he found more than 1000 vessels, including jars, dishes, jugs, bowls, and plates. Locus 114 also contained what might be seen as a “dining set,” with 40 plates and 40 goblets as well as other associated wares. Loci 111 and 121 in the western part of the settlement are adjacent and might have served as smaller areas for ritual dining. The water system looked to serve not only the daily needs of a group living in the arid Arava, but also many of the pools appeared to be suited for ritual cleansing as well. The remains of meals (bones of sheep, goats, and cattle), carefully deposited in the open spaces of the settlement, (especially in loci 130, 132, 136 in the northwest and loci 90 and 98 near the south walls) sometimes in closed vessels, seemed to reflect some sort of cultic practices.

Although Magen Broshi, Jodi Magness, Yaaqov Meshorer, and others have suggested important modifications in de Vaux’s original chronology (i.e., no period Ia at Qumran, moving the sectarian occupation to the 1st century BCE; no abandonment of the site from 31 BCE to 4 BCE), his essential interpretation of the site as a sectarian settlement still makes the most sense. Professor Magness has also convincingly interpreted the pottery of Qumran as an archaeologist should, in terms of what we might deduce about the community that used these items. Jean-Baptiste Humbert has developed a comprehensive reinterpretation of the archaeology of Qumran, revising some of de Vaux’s views, but nonetheless understanding the settlement as an Essene place of ritual sacrifice and worship.

Given the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, and the now excavated site of Qumran, we face a number of very limited possibilities. First, is the library we know as the Dead Sea Scrolls indigenously connected or unconnected to the site of Qumran? If so, we can now combine the work of spade and text in a way that was impossible with the classical sources, in that the texts themselves are an integral part of our material evidence. Second, do the Scrolls represent a coherent group? Finally, if they represent a group, is it one known or unknown to us in sources outside the corpus? The answers appear to be yes, yes, and yes.

However, this “consensus” is not without its detractors. Norman Golb has argued that Qumran is a military installation or fort.[15] Pauline Donceel-Voûte has put forth the interpretation of Qumran as a villa rustica.[16] Most recently Yizhar Hirschfeld has published his grand interpretation of Qumran as a manor house of an agricultural estate—wholly unconnected to the sectarian life reflected in the Scrolls.[17] Although these views have been exhaustively reviewed and critiqued, particularly by Jodi Magness and Magen Broshi, the press continues to sensationally report that the “consensus” has been broken, as if some vast academic conspiracy has been at work promoting the so-called “Essene Hypothesis.”[18]

We are not certain who first suggested the Scrolls from Cave 1 might be connected to the Essenes. It was most likely Eleazar Sukenik, professor of archaeology at Hebrew University, who viewed both the Thanksgiving Hymns and the War Scroll in the days following November 29, 1947. John Trevor, however, reports that in February 1948, Father Butrus Sowmy’s brother, Ibrahim, who was a customs official at the Allenby Bridge suggested such a connection, when the two brothers brought four of the texts to him and William Brownlee at ASOR (1QS, 1QHab, Isaiah, GenApoc). In the April, 1948 ASOR news release, three Protestant scholars living at ASOR, Burrows, Trevor, and Brownlee, speculated that the Community Rule, at least, might be connected to some “little known monastic order, possibly the Essenes.”

Now that we are in a position to examine closely the entire corpus it seems to me that we can definitively identify the Dead Sea Scrolls group, first, with the site of Qumran, and second, with the ancient “sect” of Judaism known to us in classical sources as the “Essenes.” With Stephen Goranson and others, I find the link between the Greek forms of the term “Essene” and the Hebrew term “doers of the Torah,” to be most convincing. We are operating here in the thought world of Daniel 11:32 and associated texts. Though there are important differences in our indigenous and classical texts (did the group completely shun sacrifice, slavery, marriage, and warfare as Philo would have things?), and many remaining issues to resolve at the site itself, from an archaeological perspective, the “fit” between classical texts, Scrolls, and the site of Qumran is rather striking. Students, media representatives, and the general public often ask—do you agree that the group that wrote the Scrolls were the Essenes? One is tempted to reply—yes, but how does one know what an “Essene” is in the first place? This is a label, a single word, and by positing the identification we are really only affirming that Pliny, Philo, and Josephus indeed know and mention a group by this name, not that their descriptions can be taken as hard historical evidence.

As a bare label it is hardly more helpful than the label of “Sadducee” that Shiffman, Reeves, and others prefer, based on certain halachic positions taken in some scroll documents (mostly MMT). We have long realized that the highly stylized reports of Pliny, and more especially Philo and Josephus, were more social and cultural propaganda than historical reporting, though they surely contain accurate information on the Essenes. Like the stock praises of the Gymnosophists of India in pseudo-Callisthenes’ Alexander Romance or Philostratus’ Apollonius of Tyana, or the idealized portraits of the Magi that run through ancient Mediterranean literature, both Philo and Josephus want their readers to know that among the Jews there are indeed are these highly virtuous souls, dedicated to spiritual pursuits. For Josephus, the Pharisees are like the Stoics, the Sadducees like the Epicureans, but most admirable of all, the Essenes, are like the ancient Pythagoreans. As with his description of the Pharisees, in terms of their views on Fate and immortality of the soul, he is writing for his Roman audience, who would find the actual Pharisaic halachic system, with which he surely must be familiar (as reflected in early parts of the Mishnah and other rabbinic tradition), completely alien and strange.

“Essene” or not, it is the content of the scrolls themselves, and the material evidence at Qumran that should have privilege. Did Josephus know, but not tell, that the “Essenes,” were an intensely xenophobic, anti-Roman, contra-establishment, messianic, apocalyptic, “baptist” wilderness group that saw itself as living in Daniel’s “time of the end?” It might well be that his reasons for not letting those “cats out of the bag” has to do with his sympathies with the Essenes themselves in the volatile post-Revolt atmosphere, living in Rome in the former palace of Vespasian. He does let us know in several places that they were skilled in the interpretation of prophecy. His apologetic purposes in both the Jewish War and the later Antiquities are well documented.

In the grand hierarchy of things there is a sense in which we must allow the material evidence to predominate. Whatever theory we have about the site of Qumran, and however dependent it might be on the reading of our texts, whether classical or the Scrolls, ultimately it must be tested on the ground. As James Strange has put it, what we need is an open investigation of the entire site and all its environs backed by a series of testable hypotheses that can actually yield results. Such hypotheses are not to be formulated in isolation from our texts. Indeed, as often as not, the texts themselves suggest to us certain possibilities that would not have otherwise occurred to us.

Hershel Shanks, editor of Biblical Archaeology Review, once put it like this to Qumran archaeological spet Jodi Magness: Would we interpret Qumran as a sectarian religious settlement had the Dead Sea Scrolls not been found? In other words, to what degree does our reading of the Scrolls shape and form our interpretations of the material, almost wholly non-textual evidence, found at the site itself? Magness replied that she did not think we would interpret it as a religious settlement, but neither would we conclude it was a villa or a fortress. The site would remain anomalous because it has too many unusual features that resist any standard interpretation (especially the extensive ritual baths, animal bone deposits, and cemetery). She then remarked—but why would we want to disregard the evidence of the Scrolls? They appear to be an integral part of the archaeological evidence and can provide us with indispensable clues as to how to interpret the non-textual data.[19]

In looking at Qumran with and without the texts, and the texts with and without Qumran, one must first distinguish between two very different types of textual evidence. On the one hand we have the scrolls and ostraca, which are themselves part of the archaeological data, being subject as material evidence to paleographic, AMS, DNA, and other types of scientific testing. Yet, as texts, they also offer us insight into beliefs, practices, and history, any of which might shed light on the material evidence at the site of Qumran, or vice versa. On the other hand, we have our classical sources on the Essenes, which though textual, and thus providing witness to beliefs, practices, and history as well, are decidedly non-archaeological and non-indigenous. In order to work our way through this rich “evidential” complex it is important that we carefully distinguish, at every turn, what type of evidence we are using, how it might look in isolation or in combination, and what assumptions go into our constructions and conclusions. How might one read the sectarian scrolls along side the classical sources on the Essenes? Can those results in turn be connected or correlated with the material record, and with what methods and assumptions? Finally, what happens when one goes “hunting” for material evidence with texts in hand?

Over twenty years ago when I first worked with Robert Eisenman at Qumran I became intrigued with the question of whether one could find any correspondence between the unusual “toilet” practices of the Qumran sect as described in the Scrolls, Josephus’s description of Essenes, and what we could locate “on the ground” at the site. The texts in the Scrolls that caught my attention in particular were the following:

A man may not go about in the field to do his desired activity onthe Sabbath. One may not travel outside his city more than a thousand cubits (CD 10:20-21).

Between all their camps and the latrine there shall be a space of about two thousand cubits, and no shameful nakedness shall be seen in the environs of all their camps (1QM 7:7).

You are to build them a precinct for latrines outside the city. They shall go out there,on the northwest of the city: roofed outhouses with pits inside,into which the excrement will descend so as not to be visible. The outhouses must bethree thousand cubits from any part of the city (11QT 46:13-16)

Here we have in The War Scroll and The Temple Scroll the requirement that the community locate its latrines “outside the camp,” with the distances of two thousand, and in the case of the ideal Jerusalem of the future, three thousand cubits, from the camp or city. This is based on the commandment in the Torah requiring such, though the precise distance is not specified:

You shall have a place outside the camp, and you shall go out to it. And you shall have a trowel with your tools, and when you sit down outside, you shall dig a hole with it and turn back and cover up your excrement. Because the LORD your God walks in the midst of your camp, to deliver you and to give up your enemies before you, therefore your camp must be holy, so that he may not see anything indecent among you and turn away from you (Deuteronomy 23:12-14).

This notion of separating the ordinary or profane, from the holy, is of course found throughout the Torah–whether menstrual blood, seminal emissions, or the contamination of a corpse–reflecting the notion of not only the holiness of the sanctuary but that of the “camp” of God’s people themselves who live in the presence of God.

The problem of course came on the Sabbath when one was not allowed to go “outside his place” according to the Torah (Exodus 16:29). What constituted the allowed distance for travel on the Sabbath, the proverbial “Sabbath day’s journey,” as well as the “bounds of the camp” are defined here in the Community Rule as a thousand cubits. The obvious problem is how then is one to go to the toilet on Shabbat if the latrines are located anywhere from two to three thousand cubits “outside the camp.” Josephus, in explaining the toilet practices of the Essenes, draws special attention to this problem:

Moreover, they are stricter than any other of the Jews in resting from their labors on the seventh day; for they not only get their food ready the day before, that they may not be obliged to kindle a fire on that day, but they will not remove any vessel out of its place, neither to go aside [to relieve themselves]. Nay, on the other days they dig a small pit, a foot deep, with a paddle (which kind of hatchet is given them when they are first admitted among them); and covering themselves round with their garment, that they may not affront the divine rays of light, they ease themselves into that pit, after which they put the earth that was dug out again into the pit; and even this they do only in the more lonely places, which they choose out for this purpose; and although this easement of the body be natural, yet it is a rule with them to wash themselves after it, as if it were a defilement to them (War 2:147-149).

Indeed, Josephus sees this practice of not going to the toilet for 24 hours on the Sabbath day as a sign of the utter dedication of the group to the Torah with its dual prohibitions regarding travel on the Sabbath and the location of latrines.

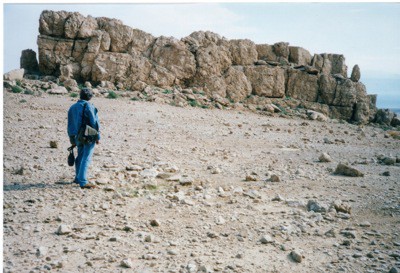

In 1995 the idea occurred to me to begin looking at the site of Qumran, especially to the northwest, to see if there might be any material evidence that would support this practice. Going northwest of the site one encounters an natural rock formation and a flat area leading up to the limestone cliffs that border the “camp” on the west and north. In examining that area, first visually, then with radar ground scan, and finally, enlisting the partnership of Joe Zias and Stephanie Harter-Lailheugue, we carried out selective soil tests. I am convinced we located the toilet area of the community. In 2006 we published our findings in the peer-reviewed journal Revue de Qumran, which you can read below. We were impressed that what we found “on the ground” corresponded so closely to what we found described in both the Scrolls and the literary account of Josephus. It seemed to us to be one of those “rare fits” between text and site and we hope it has advanced our discussion of the issue of how the site of Qumran and the community that produced the sectarian Dead Sea Scrolls might be connected.

But what we never could have guess or imagined or predicted came with this discovery. We are convinced the sanitation processes that this dedicated and pious group followed, ironically, let to a high rate of disease and infection, leading to many of the community dying at abnormally young ages. You can read the full details in our published articles.

https://jamestabor.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Toilets-at-Qumran.pdf

[1] Divine Drudgery: On the Comparison of Early Christianities and the Religions of Late Antiquity (Chicago, 1990).

[2] Excavating Jesus: Beneath the Stones, Behind the Texts (New York: HarperSanFrancisco, 2002). See also the more sensational and less successful attempt by Richard Batey, Jesus and the Forgotten City: New Light on Sepphoris and the Urban World of Jesus (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1992).

[3] See the excellent survey by James Vanderkam and Peter Flint in The Meaning of the Dead Sea Scrolls (New York: HarperSanFrancisco, 2002), 34-36, to whom I am mostly indebted for the following references. Compare Jodi Magness, The Archaeology of Qumran and the Dead Sea Scrolls (Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans, 2002), 22-24 and bibliographical notes, 29-30. More generally see Neil Silberman, Digging for God and Country:P Exploration, Archaeology, and the Secret Struggle for the Holy Land, 1799-1917 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1982).

[4] “Relation du voyage,” Voyage autour de la Mer Morte et dans les terres bibliques, exécuté de décembre 1850 àvril 1851 (Paris, 1853): 2:165-67, published in English (London: Richard Bentley, 1854), 55-68.

[5] Voyage dans le Haouran ex aux bords de la Mer Morte, exécuté pendant les années 1857 et 1858 (no date), 223, 227.

[6] Claude Condor and Horatio Kitchener, The Survey of Western Palestine (vol. 3 Judea; London: Palestine Exploration Fund, 1883), 210-211. Tywhitt-Drake died of malaria on the expedition and was replaced by Kitchener.

[7] “Kumrân,” Archaeological Researches in Palestine During the Years 1873-1871 (2 vols., London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund, 1896) 2:14-16.

[8] See Palestine Exploration Fund Quarterly Statements from 1902-1913, especially 1902: 161-62; 1903: 265-67.

[9] Une Croisiére autour de la Mer Morte (Paris, 1911), 164-68.

[10] Palästinajahrbuch des Deutschen evangelischen Instituts für Altertumswissenschaft des leiligen Landes zu Jerusalem10 (Berlin: Ernst Siegfriend Mittler, 1914), 9-10; 16 (1920), 40.

[11] Das Buch Josua (HAT 7; Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 1938), 72.

[12] See Stephan Pfann, “Sites in the Judean Desert Where Texts Have Been Found,” in Companion Volume to the Dead Sea Scrolls on Microfiche Edition (ed. Emmanuel Tov with Stephan Pfann; 2nd rev. ed.; Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1995), 110.

[13] Pfann, “Sites in the Judean Desert,” 110.

[14] David Horowitz, Thirty-three Candles (New York: World Union Press, 1949), 35-47.

[15] Norman Gold, Who Wrote the Dead Sea Scrolls (New York: Scribner, 1995).

[16] Pauline Donceel-Voûte, “Les ruines de Qumran reinterprétées,” Archeologia 298(1994): 24-35.

[17] Yizhar Hirschfeld, Qumran in Context (Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson, 2004).

[18] See particularly Jodi Magness, The Archaeology of Qumran (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2002) and Magen Broshi, “Was Qumran, Indeed, a Monaste4ry? The Consensus and Its Challengers, an Archaeologist’s View,” in Caves of Enlightenment: Proceedings of the American Schools of Oriental Research Dead Sea Scrolls Jubilee Symposium (1947-1997), ed. James H. Charlesworth (North Richland Hills, TX: Bibal, 1998), 19-37. Israeli archaeologists Yitzhak Magen and Yuval Peleg support Hirschfeld’s view based on their latest findings at the site, namely jewelry and precious glass.

[19] See Magness, Archaeology of Qumran, 13.

Comments are closed.