All across the world this morning, moving from east to west, Easter bells are ringing. Multiple millions will gather in churches to celebrate Easter–“Rejoice! Christ is Risen!” will be the theme of every service. Without exception texts of the gospels reporting on the first Easter and the discovery of Jesus’ empty tomb–along with his appearances to his followers–will be read. In the New Testament gospels we have four rather complex and ofttimes contradictory accounts of what happened Sunday morning after Jesus was crucified–so there is quite a mix to choose from (Mark 16; Matthew 28; Luke 24; John 20-21). Liturgical traditions have a set of these texts already designated. More independent groups will go with whatever their minister or preacher has prepared for the Easter sermon. What almost everyone will miss is the following:

Embedded in these layers of tradition are ten verses that appear to be the earliest narrative–and one that rings historically more likely given all the circumstances of that fateful weekend. Although these verses are found in the Gospel of John, one of our latest gospels, this little fragment of tradition stands alone and unique.

Here are those verses:

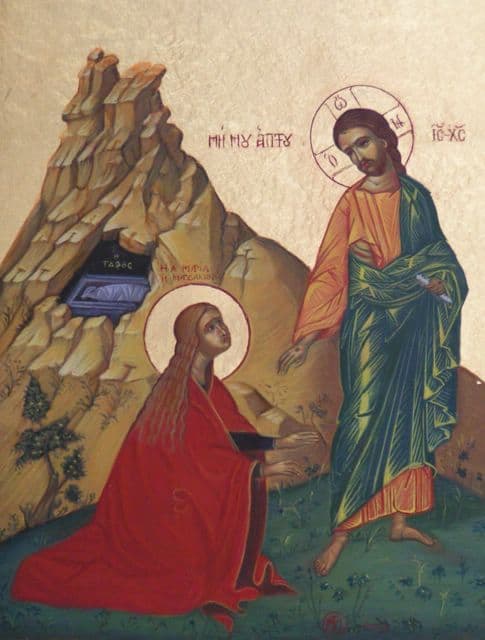

Now on the first day of the week Mary Magdalene came to the tomb early, while it was still dark, and saw that the stone had been taken away from the tomb. So she ran, and went to Simon Peter and the other disciple, the one whom Jesus loved, and said to them, “They have taken the Lord out of the tomb, and we do not know where they have laid him.” Peter then came out with the other disciple, and they went toward the tomb. They both ran, but the other disciple outran Peter and reached the tomb first; and stooping to look in, he saw the linen cloths lying there, but he did not go in. Then Simon Peter came, following him, and went into the tomb; he saw the linen cloths lying, and the napkin, which had been on his head, not lying with the linen cloths but rolled up in a place by itself. Then the other disciple, who reached the tomb first, also went in, and he saw and believed; for as yet they did not know the scripture, that he must rise from the dead. Then the disciples went back to their homes. (John 20:1-10).

That is it. Short and simple. What it does not say is as important as what it does say:

- There is no group of woman coming just after sunrise

- There is no earthquake

- There are no angels appearing and proclaiming “Christ is risen”

- There are no Roman guards knocked out cold from the terror of it all

- There are no men in white garments

- There is no resurrections of the “saints” who have recently died

- And most important: There are no appearances to anyone.

Notice carefully: What Mary, the unnamed “Beloved” disciple, and Peter “believe” is that the body has been taken away, not that Jesus has been raised from the dead! This is made explicit in this text.

Now all of these elements appear elsewhere in the accounts of Mark, Matthew, Luke, and John, cited above. But this little fragment of tradition clearly stands alone, in “silent” contradiction and start contradistinction from the Easter tradition as a whole.

I am convinced this passage preserves an independent embedded early tradition that centered on the mysterious Mary Magdalene that was passed on to John’s community through the equally mysterious “Beloved Disciple.” [1]See my series “There is Something About Mary–Magdalene, and Who Was the Mysterious Disciple Whom Jesus Loved?

Notice the three main elements of this text:

- Mary Magdelene came alone before before sunrise–while it is still dark and she discovered the tomb already open and drew the obvious conclusion–namely that “they” had moved the body and placed it elsewhere. [2]See my article, “The First and Second Burials of Jesus.”

- The “they” in this context is clearly those in charge of Jesus’ permanent burial–namely the Joseph of Arimathea burial party–Jesus’ corpse had been temporarily stashed in this unfinished and as yet unused tomb nearby the site of crucifixion just an hour or so before Passover (John 19:41-42).

- Peter and the “beloved disciple” rush to the tomb, confirm the body has been “taken away,” and return to their homes in the Galilee–which fits well with the parallel tradition we have in the lost Gospel of Peter. There the disciples weep and mourn and return to Galilee to resume their fishing still in despair.

In this text and this text alone: Mary Magdalene, with her unique and special connection to Jesus came alone early that morning, most likely to mourn at the tomb and await the others to finish the rites of burial. This simple “bare bones” account rings true. The subsequent accounts here in John, as well as in Mark, Matthew, and Luke all are part of the typical “myth-making,” literary expansion, and theological embellishment–40 to 60 years after Jesus’ death. One would expect that these Christian communities begin to bolster their faith stories in the face of skeptical opposition. That is why all of the subsequent accounts have an “apologetic” tone to them–with some doubting and more and more “proof” being offered that the “sightings” of Jesus were more than apparitions. These ten verses seems to be a primitive core account that is then later embedded in the larger narrative of John’s gospel with physical appearances in Jerusalem and Galilee and all the trappings we have come to associate with Easter.

How, when, and why the disciples began to have experiences of “sighting” Jesus is another question that I have explored in depth, see “What Really Happened Easter Morning–The Mystery Solved.” But this simple primitive account gives us much to ponder this Easter weekend–and along with Mark’s account which has no appearances of Jesus–it allows us to begin to reconstruct the birth of the Easter tradition from its beginnings. [3]See “The Strange Ending of the Gospel of Mark and Why it Makes all the Difference.”

Comments are closed.