Carefully re-reading the late and sorely missed Jane Schaberg’s book, The Resurrection of Mary Magdalene, which I heartily recommend to all my readers, has set me to thinking and working through all the texts related to her once again, particularly those in our New Testament gospels. I wanted to do a bit of “thinking aloud” here, covering various thoughts and ideas that have come to me of late.

According to Paul the first named witnesses to Jesus’ resurrection was “Cephas” or Peter and James the brother of Jesus, along with the Twelve, other apostles, and a group of 500 “brothers,”and finally, much later, Paul himself (1 Corinthians 15:8). Curiously–or not so curiously–given Paul’s culture and the denigration of women, Mary Magdalene and the group of women who first discovery the empty tomb, according to all our gospels accounts, go unmentioned. In the gospels not only is Mary Magdalene at the core of the narratives, but she is mentioned first, as head of the entourage of women followers of Jesus from Galilee, even ahead of Jesus’ own mother, and in two of our accounts (Matthew and John) she becomes the “first” witness to Jesus’ resurrection.

I begin with Mark, whose references to Mary Magdalene form the core of the Synoptic gospels account of her. He mentions her three times, at the crucifixion, at Jesus’ burial, and at the empty tomb on Sunday morning (Mk 15:40-41; 15:47; 16:1). She is named first among two other women from Galilee, Mary the mother of James and Joses, and Salome, but according to Mark they are part of a larger contingent of “many other women” who had followed Jesus from Galilee where they had provided (Greek: diakoneo) for him. This reference to a large group of Galilean women who form a base of support, presumably financial and otherwise, is something Luke picks up on and elaborates (8:1-3), but it fundamentally comes to us from Mark. I presented arguments in my book, The Jesus Dynasty, that this second Mary of Mark’s group, is Jesus’ mother, with Salome most likely his sister. At any rate, it is these three, led by Mary Magdalene, who make preparations to attend to the intimate task of preparing the corpse of Jesus for burial, buying spices on Saturday evening with the intention of anointing his body early Sunday morning. Thus they come to discover the empty tomb early Sunday morning.

Matthew, clearly relying on Mark as his source, has the same three references to Mary Magdalene, at the crucifixion, the burial, and early Sunday morning at the tomb. She is paired with the “other Mary,” and he does not name Salome, though he implies she might be the “mother of the sons of Zebedee. Regardless, it is the two Marys who witness the burial and visit the tomb Sunday morning (Matt 27:55-56, 27:61; 28:1).

Luke, also following Mark, makes some significant changes to Mark’s basic structure. He too has women from Galilee standing at the cross but he names none of them (Luke 23:49). Likewise, at the burial, these women from Galilee remain unnamed (Luke 23:55-56). Finally at the empty tomb he says the women who came to complete the rites of burial were Mary Magdalene, Joanna, Mary the mother of James, and “the other women with them” (Luke 24:10). This means that Luke only names Mary Magdalene once in the three scenes that Mark has introduced her.

As we will see, this is absolutely deliberate and calculated. What he does is introduce her much earlier, back in Galilee, among this group of many women who had provided for Jesus, picking up on Mark’s reference. But there he adds that she was part of a group of women who had been cured of “evil spirits and infirmities” naming Joanna and another woman, Susanna, but adding that Mary Magdalene herself was positively deranged beyond description, in that she had been possessed by seven demons! (Luke 8:1-3). Luke is keen to make the point that the presence of these women, who do not need to be even named, is of no credible importance, since they come from such shady backgrounds, epitomizing the hysterical “female” whose testimony would be considered an “idle tale,” thus preparing the way for the true and reliable male witnesses to Jesus’ resurrection (Luke 24:11). All he really has to go on is Mark, but he skillfully recasts Mark’s material in this way, thus marginalizing Mary Magdalene, and “demonizing” her, quite literally, cured or not, lest anyone might think the resurrection faith was first proclaimed by such a witness. But there is more. Just before Luke introduces the deranged woman in chapter 8, as followers of Jesus from Galilee, he constructs a scene, in Galilee, of an unnamed woman of an unnamed city, a “sinner,” who comes to Jesus at a dinner with an ointment, who then weeps uncontrollably, bathes his feet with her tears, wiping them with her hair, and anointing them (Luke 7:36-50). Jesus forgives her many sins, and she presumably becomes his follower. And thus Mary Magdalene is introduced in the next passage. The juxtaposition is deliberate. Although Luke is not bold enough to say that Mary Magdalene herself is this forgiven harlot, the contextualizing is enough, coupled with her deranged mental past. Interestingly enough, Mark also has a story of an anonymous woman anointing Jesus, but it is a few days before Jesus’ death, in Jerusalem, and she is honored not as a forgiven sinner, but one whose anointing prepared him “beforehand” for his burial (Mark 14:3-9).

What Mark tells us then about Mary Magdalene is that she is first among a group of women from Galilee who provided for Jesus, that she is involved along with his mother, in the intimate rites of preparing Jesus’ body for burial, and that she, Mary, and Salome, are the “first witnesses” to Jesus’ resurrection. Mark knows nothing of appearances of Jesus to these women, but they hear the proclamation, “He has been raised, he is not here.” The disciples, led by Peter, are to “see him in Galilee,” though such a scene is never reported by Mark. Matthew elaborates Mark’s disturbingly sparse account, with Jesus subsequently encountering the women who linger at the tomb, and a mysterious “foggy mountain” appearance to the Eleven somewhere in Galilee (with some doubting!). Luke feels compelled to go further. There is no disputing the women were involved, at the cross, the burial, and the empty tomb–but as a group they are unnamed, and even when named, identified as “formerly” deranged and contextualized with the unnamed “harlot” whom Jesus forgives for her many sins. Luke wants nothing of appearances in Galilee, nor of the deranged women who might have proclaimed such as “first witnesses.” For him the resurrection of Jesus rests solidly on his Jerusalem based appearances to reliable male witnesses, including to Peter and the Eleven.

And then there is the gospel of John. John also has Mary Magdalene at the cross, and he clearly identifies Jesus’ mother there as well. He does not mention the women at the burial but his account of what happened early Sunday morning is significantly different from that of Mark. Rather than the group of women arriving together, John relates that Mary Magdalene came alone, very early, while it was still dark, and saw the stone removed from the tomb (John 20:1-10). She runs to tell Peter, and he, and an unnamed disciple rush to the tomb, confirming her story, but not yet coming to the conclusion Jesus was raised. There are no messengers, angelic or otherwise, as in Mark, Matthew, and Luke, to tell the women Jesus is raised–it is simple a case of someone having “taken the master out of the tomb, and we do not know where they have laid him” (20:2).

I find this account in John strangely compelling. Mark’s young man in white linen, proclaiming Jesus is risen, seems wholly theological, not to mention Matthews fantastic expansion where we have a dazzling angel who comes like lightening from heaven, heralded by an earthquake, who rolls back the stone and proclaims Jesus is risen. Luke’s two men in dazzling clothing is cut from the same cloth. In contrast, John’s core account has nothing fantastic or even theological. It deserves our careful attention, and at the heart of this account is the singular experience of a woman–namely Mary Magdalene.

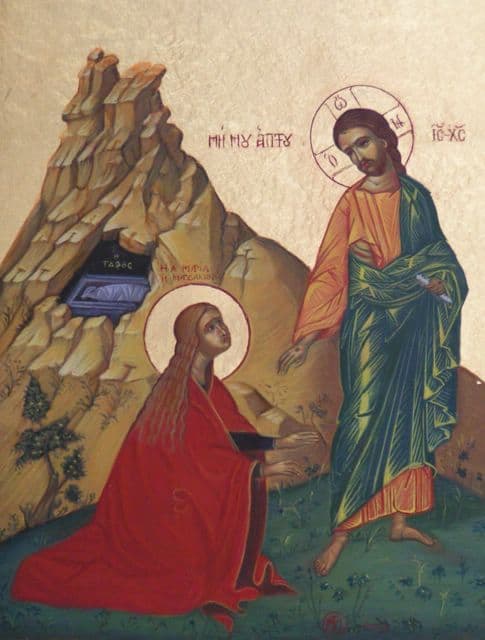

According to John the tomb is found empty very early Sunday morning, even at dark. The logical conclusion is that someone has removed the body and placed it elsewhere, perhaps the gardener, or as the rumor in Matthew has it, some of his disciples. Schaberg effectively argues, in my judgment, that what happens next in John’s gospel (20:11-18), namely Jesus’ encounter with Mary Magdalene, still in the garden near the tomb where he was missing, is our earliest and most fundamental witness to Jesus’ resurrection, and that further, the form and structure by which John narrates this encounter, implies an Elijah-Elisha like succession story, of Jesus passing on this witness to his chosen and intimate follower, Mary Magdalene. In this extraordinary account we have dialogue between Jesus and Mary. She is Maria in the narrative but Jesus calls her name directly, “Miriam,” and she replies with the affectionate diminutive “Rabbouni,” my dear/little Master. What she is told is that she must not grasp him for he is ascending to the Father.

Like Matthew and Luke, John includes other appearance stories, both to the disciples in Jerusalem, and in Galilee. But this core account, found now in John 20:1-18, is perhaps our best window for reconstructing what might have happened that early Sunday morning. Based on the Mary Magdalene account, found only in John, I am convinced that the discovery of the empty tomb should be given historical weight. It is what John’s account does not say that makes it compelling. With no angelic messengers proclaiming the resurrection, and Mary not even told to go tell the rest that they too would see Jesus, it seems to me we should give the Mary Magdalene story priority. The subsequent accounts of Mark, Matthew, Luke, and even the supplemental accounts in John, all seem to be accretions to this core account.

Mark does not dispute that Mary Magdalene and the other women first discovered the tomb, but his account is clearly a generalized expansion of an earlier core story, much elaborated by Matthew, and radically re-contextualized by Luke. But they do not venture to remove the Magdalene. Only Paul does that, in his roll call of appearances of the heavenly Jesus in 1 Corinthians 15:1-11. There Mary Magdalene is completely eliminated. In effect, that has already begun to happen in Mark, since the women “say nothing to anyone” and are mainly pointers to the male Eleven who will see Jesus in Galilee. In Matthew the main point of resurrection is the “commission,” and that would not be given to women, but only to the male Eleven. Likewise in Luke, who has Jesus appear to the Eleven, telling them to take his message to all the nations.

In my view John 20:1-18 stands separate and isolated from all these subsequently embellished traditions. John is able to contextualize it with subsequent appearances to the male leaders, but read as “first testimony” it has a most compelling ring to it. I find it the only account that lends itself to some measure of credible historical reconstruction. It essentially is what I make most use of in my own reconstruction in The Jesus Dynasty:

Jesus is hastily buried in a temporary tomb that happened to be nearby in a garden at the place of crucifixion. The intent was to move his body to a permanent place after the festival/Sabbath was past. Mary Magdalene arrives early Sunday morning, while it is still dark, and finds the stone rolled away and the tomb empty. She alerts Peter and the others. No one thinks Jesus has been raised, but they draw the logical conclusion, that someone has moved him. Presumably that someone would be either other family members, or more likely Joseph of Arimathea. Lingering near the tomb Mary has a visionary encounter with Jesus himself. She is told by him that he is ascending to heaven and that is what she reports to the others. Mary then becomes first witness, and as such, “successor” to the ascending Jesus. She alone is given the message–Jesus has ascended to the Father.

It is difficult to read this account as it stands without interjecting subsequent stories from Matthew, Luke, and John. But that Mark, writing as late as the 70s AD, has no appearances, yet he does have Mary Magdalene at the tomb, supports the essential core of John’s Mary Magdalene story. Historians have rightly judged that the series of expanded and dramatic appearances of Jesus to his various male followers are theologically cast apologetics. As such, the singular appearance to Mary Magdalene, did not fare so well. Luke begins the long history of her demise and defamation–yes, she was there, but remember, she and the others were surely less than reliable witnesses. What is important is that even in Mark she can not be eliminated. She is there at the first, and she is clearly the first, if John is to be given any weight at all.

One puzzle in John is that he, like Mark and Luke, also has a scene at which Jesus is anointed by a woman (John 12:1-8). His account is clearly parallel to that of Mark in several of its key elements, but then it departs significantly therefrom. John’s story takes place a few days earlier than Mark’s, six days before Passover. John identifies the woman as Mary of Bethany, sister of Martha and Lazarus, whereas Mark leaves her unnamed. Rather than Jesus’ head, as in Mark, this Mary anoints his feet with a costly perfume and wipes them with her hair–which in turn reminds one of the Luke story of the “woman of the city,” that is the “sinner.” In John Jesus does not say that she has anointed him beforehand for his burial, but rather that the costly perfume was well spent and that she can store it up to use in the future on the day of his burial! One would then expect her to appear in some manner, at the burial scene, to anoint Jesus’ body, as Mark has Mary Magdalene do. I see no easy way to sort through these three anointing stories. I think behind them lies some event that took place the last week of Jesus’ life, in Jerusalem. We can surely discount Luke’s moving the story much earlier, and placing it in Galilee, as well as his implication that the woman who anoints Jesus is a “sinner.” But that Luke juxtapositions his redeemed harlot story with his own introduction of Mary Magdalene as formerly “deranged” or demon possessed, gives one pause. Does Luke fear that Mark’s story might imply that the anointing woman is none other than Mary Magdalene–who subsequently comes to the tomb to complete her prophetic or proleptic act of devotion? The intimacy implied in John’s story, namely the wiping of the feet with the hair, given Jewish custom, is also present in Luke but not in Mark. It is all more than confusing but one is tempted to say at the core of these accounts is a story of involving intimacy, anointing, and burial. I do not think it makes sense to identify Mary of Bethany with Mary Magdalene, as some have suggested. However, it might make sense that final editors of John wanted to distance Mary Magdalene from such an intimate act by some substitution of names, whereas Mark simply leaves her anonymous.

Comments are closed.