In fact the “kerygma” or “preaching” of the apostles according to Luke, as reflected in Peter’s speeches in Acts 2:22-38 and 3:11-26, is pure “Paulinism” in terms of its basic parameters–that Christ was sent from God as Messiah, that he died for the sins of mankind, that he was raised from the dead, and that he has ascended to heaven, soon to return as apocalyptic Judge.

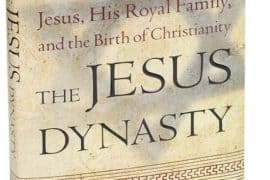

There are two widely accepted popular assumptions about early Christianity that I think one should radically question. In my book, Paul and Jesus: How the Apostle Transformed Christianity, I take on both of these head on. Get the book if you want a more in-depth treatment, but here is an overview.

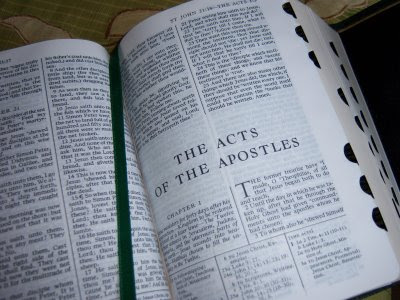

The first assumption is that the essential story line we read about in the New Testament book of Acts is an accurate version of the early years of the Jesus movement following the crucifixion. John Dominic Crossan, properly calls the period from 30 CE when Jesus was executed, to around 50 CE when we get our first letter of Paul, the “Dark Age” of early Christianity. In other words we have almost no surviving texts or evidence from this period.

The account given in the book of Acts is wholly shaped by the author’s (traditionally called “Luke”) devotion to Peter and Paul, and his commitment toward showing how everything prepared the way for Paul’s entrance on the scene and his resulting ministry. Luke links up Jesus’ final words at the end of his Gospel, namely, “that repentance and remission of sins should be preached in his name to all nations, beginning from Jerusalem” (Luke 24:47) with his final scene in Acts that pictures Paul in Rome, doing just that, preaching the gospel to the gentiles. Acts might well be called “From Jerusalem to Rome: The Story of Paul’s Triumph.” Luke is anxious of course to show great harmony between Peter and Paul, and even a kind of tacit agreement of James, the brother of Jesus, whom Luke has to reluctantly admit was the leader of the Jesus movement at that time. In fact the “kerygma” or “preaching” of the apostles according to Luke, as reflected in Peter’s speeches in Acts 2:22-38 and 3:11-26, is pure “Paulinism” in terms of its basic parameters–that Christ was sent from God as Messiah, that he died for the sins of mankind, that he was raised from the dead, and that he has ascended to heaven, soon to return as apocalyptic Judge.

Many readers can find comfort in the continuity that runs from Paul’s own rendition of the “gospel” in 1 Corinthians 15 (written around the 54 CE), or his pithy summary in 1 Thessalonians 1:9-10, and these early “sermons” of the pillar apostles, Peter and John (with James left out or muted). However, I have become convinced, along with a number of my colleagues, that the book of Acts is probably the most misleading documentin the New Testament canon. The story of what those earliest days of the Jesus movement were actually like, when James the brother of Jesus was in charge, and Peter and John were considered his “right” and “left” hand men, has been completely clouded, obscured, and eliminated.

Fortunately, this is not wholly the case. It is indeed possible to shed some light on this “dark age” of early Christianity. In fact Paul’s own letters are one of our best sources. There we can still find reflected key elements of the alternative story that Luke consciously overwrites. Indeed, I am convinced that Paul’s most vociferous enemies are in fact those he sarcastically refers to as the “so-called Pillars” of the Church, namely James, Peter, and John. And we have other sources as well, here and there, sometimes in bits and pieces and fragments. The composite picture that develops is quite astounding. What we have is a far cry from any form of faith that might properly be called “Christianity.” Rather what emerges is a Jewish sect, known in those days by the name Nazarene, that is thoroughly a part of what we call “late 2nd Temple Judaism,” every bit as much as the Pharisees, the Sadducees, the Zealots, or the Essenes. In fact, broadly considered, this “Jesus movement” might more properly be called “the messianic movement in pre-70 CE Palestine”–as Robert Eisenman has correctly noted in his various books–see the latest, Breaking the Dead Sea Scrolls Monopoly: A New Interpretation of the Messianic Movement in Palestine. It was led and shepherded by James the brother of Jesus. It’s closest parallels in terms of its apocalyptic vision of things are probably now best preserved for us in the Dead Sea Scrolls, as I have discussed in my recent post, “The Messiah Before Jesus.”

The second grand assumption about early Christianity is the portrait of its clean break with Judaism and its subsequent harmonious (despite a few evil heretics) unbroken advance into the second and third centuries. This is the tale presented to the world by that undaunted “father” of Church History, Eusebius, bishop of Caesarea (c. 300 AD). Even though many folk have not read and will never actually read his Ecclesiastical History, this composite work has fundamentally shaped the basic picture of the “advance of Christianity” that most of us have in our heads. It has become for almost everyone the “master narrative” of Christian Origins. It goes something like this:

God sent his son to die for our sins; he was raised from the dead, ascended to heaven, and he commissioned his Twelve apostles, and a bit later, Paul, as the apostle to the Gentiles, to preach the new Christian message to all the world; Christianity decisively broke with an obsolete Judaism and spread like a flame through the Roman world; despite Jewish hatred and Roman persecution the Church triumphed as the spiritual Kingdom of Christ on earth.

We now know, thanks to the discovery of and recovery of many alternative ancient sources, including the Nag Hamaddi texts found in Egypt in 1945, the newly edited and translated Pseudo-Clementine literature, the Didache, and various Syriac and Arabic sources, that what has often been called “Jewish Christianity,” was in fact the mainstream faith of the family-oriented followers of Jesus and James before 70 CE. I argue in The Jesus Dynasty: The Hidden History of Jesus, His Royal, and the Birth of Christianity that we can properly speak of a caliphate following the death of Jesus with the leadership of the Nazarene movement in the hands of Jesus’ brothers and close kin.

In fact, Paul’s influence in his own time was probably quite weak in both numbers and geographical spread until the early decades of the 2nd century. That is when Paul’s letters were edited, collected, and circulated. Mark, who basically reflects the Christology of Paul began to have its influence, and Luke, Paul’s great propagandist, published his composite work Luke-Acts. At that point the Jewish messianic movement in Palestine had been scattered by the Jewish-Roman revolt (66-73 CE), Jesus’ brother Simon, who succeeded James, had been killed, and the so-called “Jewish” followers of Jesus, scattered to the east, were known as “Ebionites” by their orthodox Christian foes.

It is really quite difficult for us to imagine a “Christianity” other than that which became orthodoxy, that is, a version of faith in which Jesus is a human being with a human father, there is no eating of the “body and blood” of Christ at the center of its liturgy, no teaching about the bodily resurrection of Jesus as the divine and preexistent Christ, Lord, Son of God, and Savior, and no assertion that the fundamentals of Jewish faith were obsolete or superseded by a “New Testament.” And yet, in fact, that is precisely what we are called upon to imagine if we really want to trace the Jerusalem based movement that arose after the death of Jesus, led and guided by his mother and brothers. My forthcoming book, The Lost Mary: How the Jewish Mother of Jesus Became the Virgin Mother of God (Knopf, 2019), will focus on this remarkable family of Mary, the matriarch of the Jesus clan, and her extraordinary role leadership and inspiration.

Comments are closed.