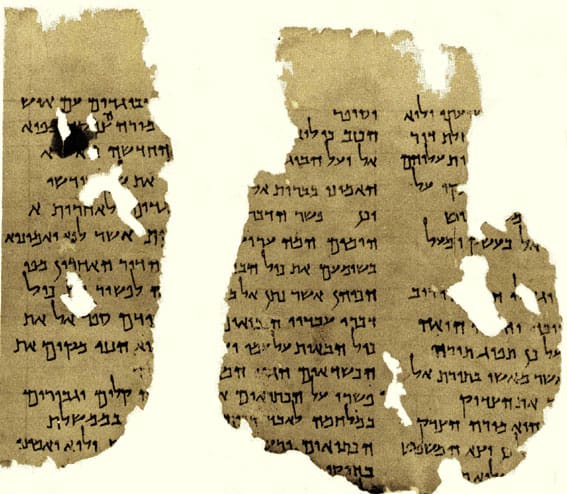

This semester I am offering an advanced undergraduate/graduate seminar on “The Dead Sea Scrolls and Earliest Christianity.” In preparation for this course I have been re-reading all of the published Dead Sea Scrolls as well as many of the secondary publications related thereto published over the past three decades. One of the more extraordinary results of the release and translation of the entire Dead Sea Scrolls corpus is our ability to sketch out a rather full and reliable portrait of the community that produced the scrolls, as well as a “life and times” of their otherwise unidentified and unnamed leader or Prophet, referred to in the Scrolls as theTeacher of Righteousness.

Remarkably, both Michael Wise, in his book, The First Messiah, and Israel Knohl, in his study titled The Messiah Before Jesus, independently picked up on this subject, neither knowing of the work of the other at the time their books were published. What makes these two studies of particularly interest is that both Knohl and Wise examine the ways in which the career of the Qumran Teacher serves as a precursor for that of Jesus of Nazareth. I highly recommend both books. Most fascinating to me is the question of what happens to the community at the death of its leader and how the prophetic vision of the future is maintained despite the failure of apocalyptic expectations–the phenomenon sociologists of religions have come to call “When Prophecy Fails.”

The complicated complex of terminology related to understanding the apocalypticism in the Scrolls–in particular the expectation, appearance, function, and outcome of various “Redemptive Figures” mentioned–has received careful attention by scholars. Among the most complete studies is that of John J. Collins, The Star and the Scepter. These designations arise, for the most part, directly from the Hebrew Scriptures–Prophet, Priest, Messiahs, Stone, Branch, Prince, Messenger, Servant, Star, Scepter, and so forth. I am using “Messiah” in my title above in the most generic sense–not merely to refer to an ideal Davidic King, but to one who is understood to function as a central figure or chief agent who ushers in the arrival of the Kingdom of God (Dan 2:44). In other words, the Scrolls, as a corpus, do not refer to just one figure but reflect a developing and shifting, even speculative application of the complexity of the Hebrew Scriptures themselves.

In one of the earlier and most foundational texts at Qumran, The Community Rule (1QS), we find no indication that any such messianic figures have appeared on the scene. Rather, the community itself expresses its self-understanding as the new covenant community of the Last Days.

Col VIII: And when these become members of the Community in Israel according to all these rules, they shall separate from the habitation of ungodly men and shall go into the wilderness to prepare the way of Him, as it is written, “Prepare in the wilderness the way … make straight in the desert a path for our God…”

Col IX: This is the time for the preparation of the way in the wilderness…

Col IX.10 ff: They shall depart from one of the counsels of the Torah to walk in all the stubbornness of their hearts, but shall be ruled by the primitive precepts in which the men of the Community were first instructed until there shall comethe Prophetand the Messiahs of Aaron and Israel.

Here we very possibly have three figures in mind. The Prophet is clearly the “Prophet like Moses” (Deuteronomy 18), elsewhere identified as the Star (Numbers 24:17) or Interpreter (Doresh HaTorah) or Teacher of Righteousness. “Messiahs”, if taken as two, most likely refers to the coming of both a Davidic “Prince of the Congregation” (elsewhere called “the Scepter”; Numbers 24:17 again), and a Priestly/Aaronic Messiah or anointed one. These are referred to in Zech 4:14 as the two “sons of fresh oil” (b’nai HaYitzhar) “who stand before the “Lord” (Adon) of the whole earth” (Rev 11). See my post on “One or Two Messiahs: What Christians and Jews Have Overlooked” for more on this topic.

Within the Qumran corpus we can document the appearance of the Prophet or Teacher of Righteousness; however, I find no evidence anywhere in the entire collection of the appearance of his two messiahs. In other words the sectarian apocalyptic community that wrote the Dead Sea Scrolls lived in expectation of a prophetic hope they never saw fulfilled.

The Damascus Document (CD) is absolutely crucial in this regard. Two manuscripts (A & B) found in the Cairo Geniza by S. Schechter in 1897 were also found in extensive fragments in Caves 4, 5, and 6 at Qumran, inside the very parameters of the settlement. The introductory lines of Col I refer to the appearance of the Teacher 390 years after the Babylonian Exile (that we now date in 586 BCE but the Scroll community clearly put it much later) and twenty years after the origin of the New Covenant movement:

He visited them and He caused a plant root to spring from Israel and Aaron to inherit His Land and to prosper on the good things of His earth. And they perceived their iniquity and recognized that they were guilty men, yet for twenty years they were like blind men groping for the way. And God observed their deeds, that they sought Him with a whole heart, and He raised up for them a Teacher of Righteousnessto guide them in the way of His heart.

What I find rather striking is that in CDmanuscript A, other than in this introduction, there is no direct reference to the arrival and career of this Teacher. Indeed, in Col VII we find reference to the “Star and Scepter” promise of Number 24 with a decidedly “future” cast to it–as if neither figure had appeared. And in Col VI we read: “He raised up from Aaron men of discernment and from Israel men of wisdom…until he comes who shall teach righteousness at the end of days.”

But in the important fragment we call manuscript B we have two additional references to the community holding fast to its mission “until the coming of the Messiah of Aaron and Israel” And, in contrast to manuscript A, we find direct references to the “gathering in” (i.e., death) of the Teacher of the Community:

Col B19: From the day of the gathering in of the Teacher of the Community until the end of all the men of war who deserted to the Liar, there shall pass about forty years.

Col B 20: None of the men who enter the New Covenant in the land of Damascus and who again betray it and depart from the fountain of living waters, shall be reckoned with the Council of the people or inscribed in its Book, from the day of gathering in of the Teacher of the Community until the comings of the Messiah out of Aaron and Israel.

What is even more striking is that CD manuscript B recasts manuscript A (Col VII) and quotes Zechariah 13:7: “Awake O Sword against my Shepherd, against the man who is my fellow, says God–smite the shepherd and the sheep shall be scattered, and I will turn mine hand upon the little ones.” This “smiting” of the Shepherd, whom I take here to be the Teacher, appears parallel in this fragment to his “gathering in.” At this very point in the text, fragment B edits out the reference in A to the Numbers 24 “Star and Scepter” prophecy–obviously seeing it as in the past. It is surely a bit more than remarkable that that precise texts from Zechariah about the “smiting” of the Shepherd is one Jesus quotes, according to the Gospel of Mark, following his final evening meal with his disciples as they crossed the brook Kidron walking to the Garden of Gethsemane at the foot of the Mount of Olives (Mark 14:26-32).

Here we find a period of “about 40 years” tied to the demise of the Teacher. There is a fragment from Cave 4 (4Q171) that refers to the same period:

“A little while and the wicked shall be no more; I will look towards his place but he shall not be there” (Psalm 37:10). Interpreted, this concerns all the wicked. At the end of the forty years they shall be blotted out and not an man shall be found on earth.”

Here things get a bit prophetically complicated, unless one is steeped in the chronological schemes of the book of Daniel (and Ezekiel)– particularly the “70 weeks” prophecy of Daniel 9. The text assumes understanding of a final 490 year period, which the Dead Sea Scrolls community understood neatly as Ten Jubilees, 49 years each. We then find references in various fragments (11QMelch; 4Q390)that attempt to fit the history of the community within this time scheme. The Teacher himself is to arise, as one would expect, “in the first week of the Jubilee that follows the nine Jubilees” (11QMelch), or just over 40 years from the End. This sort of “pinpointed” chronological placement is rather extraordinary and captures for us a moment in time, not without parallel in the 40 years from the death of Jesus in 30 CE to the “end of the age” associated with the destruction of Jerusalem by the Romans in 70 CE.

In the Dead Sea Scrolls commentary on the biblical book of the prophet Habakkuk (1QpHab) we find that the community has obviously lived through and beyond this 40 years “countdown” period with the Teacher long gone and the apocalyptic expectations of the arrival of the Kingdom of God anything but fulfilled. The Romans have by now invaded the country and propped up the puppet Hasmonean priests that the community despised as utterly corrupt (perhaps John Hyrcanus II c. 76 CE). Col I interprets the cry of the prophet Habakkuk of “How long?” as referring to the “beginning of the final generation.”

This extraordinarily precious text offers a line-by-line interpretation of Habakkuk’s prophecy, applying his message to the present life of the community. I have put the quotations from Habakkuk in italics, with the interpretation following each line:

…Write down the vision and make it plain upon the tablets, that he who reads may read it, and I will take my stand to watch, and I will station myself upon my fortress speedily [Hab 2:1-2]. [VII] And God told Habakkuk to write down that which would happen to the final generation, but He did not make known to him when time would come to an end. As for that which He said, That he who reads may read it speedily: interpreted, this concerns the Teacher of Righteousness, to whom God made known all the mysteries of the words of His servants the Prophets. For there shall be yet another vision concerning the appointed time. It shall tell of the end and shall not lie.If it tarries, wait for it, for it shall surely come and shall not be late.Interpreted, this concerns the men of truth who keep the Torah, whose hands shall not be slacked in the service of truth when the final age is prolonged. For all the ages of God reach their appointed end as he determines for them in the mysteries of His wisdom. Behold, his soul is puffed up and is not upright.Interpreted, this means that the wicked shall double their guilt upon themselves and it shall not be forgiven when they are judged…But the righteous shall live by his faith. Interpreted, this concerns all those who observe the Torah in the House of Judah, whom God will deliver from the House of Judgment because of their suffering and because of their faith in the Teacher of Righteousness. Interpreted, this means that the final age shall be prolonged, and shall exceed all that the Prophets have said; for the mysteries of God are astounding.

I think the evidence is strong, both internally and externally (dating of the texts–paleography/C-14, see Michael Wise, The First Messiah), that the crisis of belief that this text reflects had come to a climax in the mid-first century BCE. In other words, by the time of the Roman invasion of Palestine (63 BCE) and the reign of Herod the Great (37 BCE), such hopes and expectations had been severely tried and found wanting. And yet, the movement as a whole, more broadly speaking, what Robert Eisenman calls “the messianic movement in Palestine,” from the Maccabees to Masada, continues on–see his latest work, summarizing his position and responding to many of his critics, who quite frankly, have not even read his materials: Breaking the Dead Sea Scrolls Monopoly: A New Interpretation of the Messianic Movement in Palestine. Indeed, it seems to find its final expression in the hopes and dreams of the followers of John the Baptist, Jesus, and James. I think no one has shown that more clearly than Professor Eisenman.

It is against this background that I try to set my own interpretation of the life and times of Jesus the Messiah in my book, The Jesus Dynasty. With the Dead Sea Scrolls we literally have a “trial run” on the Apocalypse, with all the resulting dynamics from “delay of the End of the Age” to the brutal deaths of various leaders and Messiahs. I think it remains the case that those of us who study the historical Jesus and earliest Christianity are essentially tracing the fortunes and fate of an apocalyptic movement that functioned through the vicissitudes of Roman occupation, leading up to the 1st Jewish Revolt. This was surely the “apocalyptic heyday” of the past 2000 years and as the S. G. F. Brandon argued so persuasively in his masterpiece, The Fall of Jerusalem and the Christian Church, the watershed moment of “Christian Origins” is the destruction of Jerusalem in August of 70 CE. I consider Brandon’s work one of the most important contributions to the study of Christian Origins in the last 100 years.

Comments are closed.