Happily, I come out of a Christian tradition in which the Hebrew Bible carries as much authority as the New Testament. No different weight is given to one or the other. The Bible is one, Old and New, in my particular tradition. My own interest is far more in the Hebrew Bible. My religion is more personally related to the Hebrew Bible than the New Testament.

Professor Frank Moore Cross, Harvard University

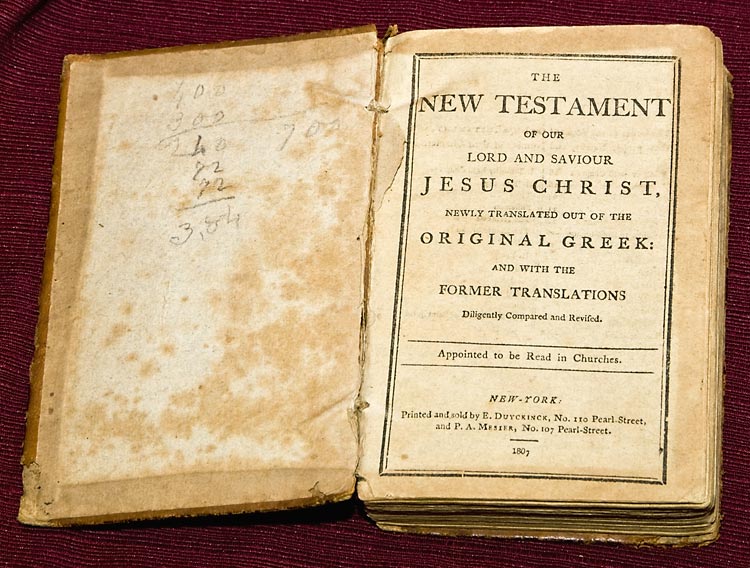

Most people today think of the New Covenant, or as it is more commonly called, the New Testament, as a book–namely the 27 documents making up the tradition canon of the Christian Scriptures. In our Western Christian world this collection, bound together with what is then called the Old Testament or the Jewish Scriptures, makes up the Holy Bible. What millions fail to realize is that this wholly new creation–at least two hundred years in the making–was unknown to Jesus, or any of the apostles–not even Paul whose letters make up over a quarter of the whole. They were all Jews and to them the “Bible” or the Holy Scriptures was the Hebrew Bible, that Jews today call the Tanakh–the Torah, Prophets, and Writings. It is this precise collection of books that Christians erroneously ended up calling the Old Testament.

It comes as a surprise to many of my students to learn that the term new covenant only occurs once in the entire Hebrew Bible–in the book of the prophet Jeremiah. Although there are examples of the Covenant God made with all Israel through Moses at Horeb/Sinai being “renewed” at various points (e.g. Deuteronomy 29:1; 2 Kings 23:1-3), the “New Covenant” of which Jeremiah speaks (31:31-34) stands out in terms of how it is both described and placed in context.

According to the apostle Paul, Jesus did speak of a “new covenant,” on the last night when he was betrayed (1 Corinthians 11:23-26). Mark knows and passes on a version of this tradition, though the word “new,” contained in some manuscripts, is likely a later scribal addition, influenced by Paul and Luke (Mark 14:24; Luke 22:20). I find it highly unlikely that Paul’s account of the words of Jesus is historically reliable, see “Eat My Body, Drink My Blood–Did Jesus Ever Really Say That? Nonetheless, it is highly likely that Jesus saw himself as the inaugurator of the “new covenant” spoken of by Jeremiah.

Much of Jesus’ mission and message is drawn from the Prophet Jeremiah. Just as Jeremiah had brought a message to Jerusalem and its corrupt leaders 40 years before the destruction of the 1st Temple in 586 BCE, Jesus saw himself repeating much of that mission, but in this case a generation before the destruction of the 2nd Temple in 70 CE by the Romans. Jesus declares the Herodian Temple a “den of robbers” based upon Jeremiah 7:11, and he declares it abandoned and forsaken by God, based upon his reading of Daniel 9:26 and Zechariah 13:7-9. According to the gospel of Mark Jesus quotes these very texts the last week of his life as he goes about his final activities in Jerusalem a week before his death at Passover. Many scholars would see the matching of such quotations with the activities and expectations of Jesus as inserted after the fact by Mark but there are good reasons to think it might have been just the opposite. Jesus is finding his messianic “script” in the Hebrew Prophets and is accordingly acting out what he considers to be his prophetic messianic role as the representative Suffering Servant who redeems all Israel. I have published several articles on this point and summarized my arguments in the post “The Making of a Messiah: Did Jesus Claim to be the Messiah and Predict His Suffering and Death?” I am convinced that Jesus both predicted and anticipated his confrontation with the Roman and Jewish authorities and willingly submitted to the suffering that he felt was his lot to endure. But what does all this have to do with the New Covenant?

If one reads carefully the wider context of Jeremiah’s “new covenant” reference, in chapters 30-31, it is abundantly clear, both by the descriptive content and the timing indicated (“At that time” “in that day” “the days are coming”), that this is a singular event to take place in a specific time when all the Tribes of Israel are gathered together back in the Land, with Judah and Israel becoming one. This event is spoken of in all the prophets with a consistency and a specificity that rivals any other theme or subject in the Hebrew prophets, and is particularly evident in Ezekiel 37, that also mentions this “new” covenant, using different words. It is a key theme throughout Jeremiah (see 16:14-21).

I think it is indisputable that this very specific vision of the future was the one anticipated by Jesus in speaking of a New Covenant. Indeed, right after referring to the New Covenant at his last meal with “the Twelve” he tells them explicitly that he chose them as apostles or envoys who would sit on “twelve thrones ruling the twelve tribes of Israel” (Luke 22:28-30). This particular tradition comes from the embedded text most scholars identify as Q–the earliest collection of Jesus Sayings–so it well might go back to the historical Jesus. Indeed, this vision is also reflected in the radical Messianic movement we see reflected in the sectarian writings of the Dead Sea Scrolls–sometimes understood as the Essenes–or at least a radical apocalyptic branch of such. See my article: One or Two Messiahs? What Christians and Jews Have Overlooked?

Although there is a sense that one might still refer to this as a “renewed” covenant, it seems to stand out as different from the various “renewals” in the previous history of Israel, so that it is understood, by analogy at least, like a divorce and a remarriage, with all Twelve tribes (the house of Israel and the house of Judah) regathered to the Land and united under the Branch or Davidic Messiah (see Jeremiah 23:3-8). Indeed, this future “regathering” of the scattered “lost” sheep of the house of Israel would rival the Exodus of Moses in terms of its scope and significance. So in that sense there is only one covenant, the one with Israel–broken but renewed in the future. This is the single Covenant with Israel commanded to a “thousand generations” (Deuteronomy 7:9; Psalm 105:8).

Given this historical context, and the clear words of Jeremiah, the term Old Testament as a term applied to the Hebrew Scriptures or Tanakh is wholly inappropriate. As someone once said, O.T. might better mean “the Only Tesament.” So where did this idea of a new covenant replacing an old one that is obsolete originate?

The answer is clear–it is wholly the creation of the apostle Paul. It is Paul who creates this dichotomy between his own work as a “minister of the new covenant” and the inferior and obsolete work of Moses that he refers to as a “ministry of death.” Indeed, he asserts that those who read the “Old Covenant” are blinded until they turn to Christ (2 Corinthians 3). In my own view, as I argue in my book, Paul and Jesus, these ideas of Paul which he begins to promulgate in the 50s CE, represent for the first time a new religion called Christianity, in contrast to the prophetic messianic message of Jesus and his first followers.

The “last” Prophetic word we have in the Hebrew Prophets is to “Remember the Teachings of My Servant Moses,” and that appears to take us to final days, characterized by the appearance of Elijah (Malachi 3/4). Rather than fade, the “glory” Moses experienced at Sinai will be renewed and enhanced in the time of which Jeremiah speaks. A simple reading of Jeremiah 30-31 belies Paul’s entire concept of a New Covenant that makes obsolete an Old, with a New Israel defined now as the Church of Christ, replacing the Jewish people whom he likens to “dead branches” broken off the tree of Abraham (Romans 11).

This is not to say that the images of putting the Torah in the heart, or having a “new heart,” that Paul makes use of, are not found in the prophetic passages that speak of the “new covenant” and its operation. They lie at the heart of things, but they are nothing new, in that these very possibilities and potentials are all at the center of the covenant Moses made with Israel. Moses constantly tells the ancient Israelites to circumcise the heart, to have hearts of flesh not stone, and to put the Torah within (Deuteronomy 10). This theme of a personal, spiritual “conversion” or turning to Jehovah is repeated constantly in the Psalms and Prophets as well. It is at the heart of the Sinai/Horeb revelation. Grace and the personal forgiveness of sins, bringing about a bonded friendship with the Creator through the Holy Spirit, has always been offered freely to human beings, and all the more so through Moses’s covenant with Israel (Psalm 51; 145:18).

Paul’s view of a “fleshly” and “spiritual” dichotomy is well known to us in all the Hellenistic dualistic systems of thought of the ancient Mediterranean world, particularly the Platonists, Pythagorians, and to some extent the Stoics. That is why he thinks what one “eats or drinks” or observing “days” has nothing to do with the “real” inner person. One of the most telling indications of this orientation toward the “heavenly” over the earthly is his assertion that “God does not care for oxen” but the Torah passage mandating care for the welfare of animals actually refers wholly to supporting preachers like himself financially(1 Corinthians 9:3-12).

A central issue when it comes to Paul is not whether he was a good guy or a bad guy, sincere or insincere, or even whether the ethical principles of the Torah are abrogated or carried through into the “new covenant” as he understands it. I have no doubt that Paul thought he was living in the “end times” and would live to see all that Jeremiah spoke of come about, at least in some “spiritual” way, since he had given up the idea that what he calls “fleshly” Israel mattered anymore. The real issue is whether one, Jew or Gentile, can have a right relationship with God by grace through faith, as Abraham had, by turning directly in repentance and faith, without the requirements of “accepting Christ” and receiving “eternal life” through the blood of the cross, as the exclusive new “way of salvation.” This is where “Christianity,” at least as viewed by Paul, parts with Judaism, and for that matter, with a plain reading of the Hebrew Bible, both Torah, Prophets, and Writings. And yet for Paul, centering everything on God offering his divine Son as a sacrifice for sins is the heart of his “new covenant” ideas (2 Corinthians 3-5). If one then turns back and reads Jeremiah 30-31 there is little to no correspondence between what Jeremiah says and the ideas Paul expounds that he calls the “New Covenant.”

Jesus himself offers something dead center in terms of reflecting the Hebrew Bible and its “way of salvation.” His well known story of “justification” given by Jesus in Luke 15 and the lost son who comes home, requires only the father’s gracious acceptance of a son who is truly broken up over his past wrong behavior. Even more to the point is his story of the tax collector or “sinner” of Luke 18 who bowed his head, struck his breast, and said “God be merciful to me a sinner.” This is the one Way of turning to God that one finds consistently in the pages of the Hebrew Bible.

Two verses from the Hebrew Bible come to mind in this regard:

Psalm 145:18: “The LORD is near to all who call upon him, to all who call upon him in truth.”

Isaiah 56:6-7: “Seek the LORD while he may be found; call upon him while he is near; let the wicked forsake his way, and the unrighteous man his thoughts; let him return to the LORD, that he may have compassion on him, and to our God, for he will abundantly pardon.”

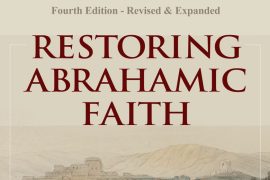

One might refer to this understanding of God and God’s relationship with humanity as “Abrahamic Faith,” taking one back to the pivotal and foundational “faith” of Abraham as reflected in the accounts of Genesis 12-22 in particular. It is a faith summarized in both the promises and the mission of Abraham as laid out in texts like Genesis 12:1-3; 18:17-19; Jeremiah 4:2). It is a path open to “all humanity,” who by taking up Abraham’s mission to represent “justice and righteousness” in the world become his spiritual offspring or “household.” I have explored this in a preliminary way in the Conclusion to my book, The Jesus Dynasty, but for those interested an approach that is much more biblically oriented there is much more in an older work of mine, now out of print, though I have a few copies around, titled Restoring Abrahamic Faith.

A personal postscript: I grew up in the Alexander Campbell/Barton Stone American”Restoration” movement which as much as any branch of modern Christianity has emphasized the New Testament as the only rule and authority for all matters of faith. We used to fight with the Baptists and Methodists “tooth and nail” for not recognizing that the Old Testament, like an outdated or abrogated “Constitution,” had been made null and void by the “New.” Ironically, it turns out, that this former “Church of Christ” kid is now allied, on this point at least, with those Christians who continued to draw spiritual insight and sustenance from the “Old Testament,” and indeed, in some cases seem to have come to prefer Jesus and the Hebrew Scriptures over the dogmas of Paul. See my blog posts: “Frank Moore Cross on the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament,” on Frank Cross, as well as my own published reflections in the Journal of Reform Judaism “Personal Reflections on the Hebrew Bible and the Greek New Testament.”

Comments are closed.