From more of this story read my book The Jesus Dynasty, available at discount prices and in all formats–Kindle, iBook, Nook, CD Audio, which also has notes and references to this material.

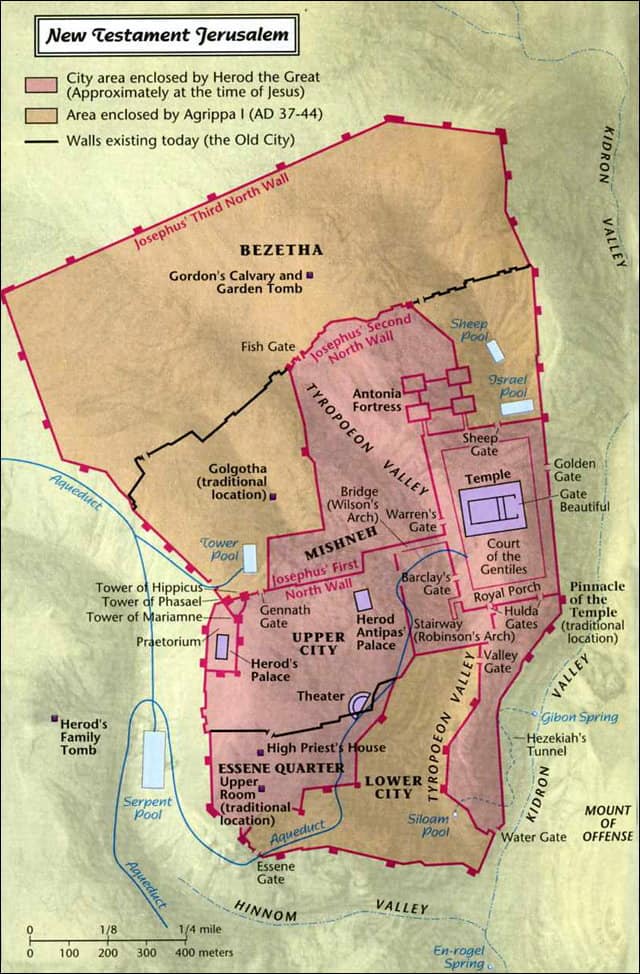

In mid March of 30 CE the time had arrived. Jesus and his entourage headed south down the Jordan River Valley to Jerusalem. It was a three-day trip and they would have camped out along the way. Passover was near, falling during the first week of April. All of Galilee were on the road, making their way to Jerusalem for Passover. The group around Jesus, however large it was at that time, likely began to swell, both with followers and the curious. There was a sense of great excitement in the air. Everyone wondered what was going to happen next. There was probably a bit of amazement that Jesus planned to openly travel to Jerusalem despite the plots to kill him by Herod and the authorities in Jerusalem.

One of the pilgrim stops mentioned by Josephus just at the foot of the Samaritan mountains is still visible along the way, with caves for shelter by the road and a natural spring. They would have reached it the first night. One should picture a group of mixed ages, men and women, with baggage and gear, and pack animals. Their social makeup was completely diverse. Most were Galileans, though Jesus had his sympathizers in Judea and Jerusalem as well, as we shall see. At the core were the Twelve, including his brothers, then his mother and sisters, Mary Magdalene, and Salome the mother of the fishermen James and John. Luke also names Joanna, married to an official in Herod’s household named Chuza; and Susanna—women of means who provided funds for the operation. Luke adds that there were “many other women” in the group (Luke 8:1–3).

The second night they reached Jericho, just north of the Dead Sea and fifteen miles east of Jerusalem. The Qumran settlement, the administrative center of the Essenes where the Dead Sea Scrolls were found, was just a few miles to the south. As the group entered Jericho a huge crowd gathered and a blind man began to cry out “Jesus of Nazareth, son of David, have mercy on me!” These were revolutionary words. They are equivalent to publicly proclaiming one as the Messiah or King of Israel. Some of Jesus’ followers tried to silence the man, knowing Jesus had forbidden such declarations in the past. Jesus stopped and called the man over, and touching his eyes said: “Receive your sight, your faith has made you well.” According to the gospels he was instantly healed, joined the band of followers, and the crowd crushing around Jesus became ecstatic with excitement. Jesus at last was ready to permit the open proclamation of his Kingship—come what may.

The group spent Saturday, the Jewish Sabbath day, in Jericho. Sunday was to prove as busy as it would be fateful. It was our March 31 but the 10th of Nisan on the Jewish calendar. Passover began at dusk as the 14th of Nisan ended, which was a Thursday just four days ahead. A final countdown had begun.

One enters Jerusalem traveling up the steep road from Jericho from the east. The Jesus party must have gained quite a bit of attention and lots more people by the time it arrived in the late afternoon at the Mount of Olives. When the group reached the summit at the little village of Bethany on the eastern side, Jesus halted the procession. He sent two of his disciples into the town telling them to find a donkey’s colt and bring it to him. Jesus sat on the animal and slowly made his way down the steep path descending the western side of the Mount of Olives, which overlooked Herod’s Temple and heart of the city. His followers began to spread garments in front of the animal as it made its way and as the crowds swelled with excitement they cut leafy branches from the trees and did the same, creating a “royal carpet” for the King. Psalm 118 celebrates the procession of one “coming in the name of Yahweh” whose festal procession is celebrated with branches of leafy foliage (Psalm 118:27). Jesus’ intention was as obvious as it was deliberate. The prophet Zechariah had written:

Rejoice greatly, O daughter of Zion; Shout, O daughter of Jerusalem: Behold, your King comes to you; he is just, and having salvation; lowly, and riding upon an ass, even upon a colt the foal of an ass. (Zechariah 9:9)

The time had come. The die was cast. Zechariah’s prophetic scenario for the “end of days” was now to unfold. By this provocative act of prophetic “pantomiming” Jesus was openly declaring himself claimant to the throne of Israel. No one who knew the Hebrew Prophets could have missed the point. The excitement and buzz about this extraordinary event ignited like sparks in tinder. The crowds began to chant explicit messianic slogans: “Hosanna to the Son of David” and “Blessed is the Kingdom of our father David that is coming.” The uproar would have been visible to anyone in the city below. Some Pharisees in the crowd, alarmed at the revolutionary implications of the scene, said to Jesus, “Teacher, rebuke your disciples.” Jesus replied: “I tell you, if these were silent, the very stones would cry out” (Luke 19:39–40).

After arriving at the city Jesus melted into the crowd. He had carried out the first stage of his plan. His purpose was not to lead a mob in revolt but to fulfill certain specific biblical prophecies. That he had done. As King he had come to “Zion,” or Jerusalem, riding on the foal of a donkey, provoking the rejoicing of the people. The words of the prophet Zechariah had been fulfilled that day.

By the time Jesus entered the city it was late in the day, and Mark says he “looked around at everything” (Mark 11:11). He likely went into the Temple compound through the southern gates, working out in his mind his plan for the following day. He returned to Bethany on the Mount of Olives by nightfall where he, his Council of Twelve, and the women were staying in the home of two sisters, Mary and Martha, who were supporters of his movement.

On Monday morning Jesus and a select band of his followers made their way down the slopes of the Mount of Olives once again and entered the Temple. On the south side of the huge Temple compound was an area where the money changers operated and where animals that were ritually acceptable for sacrifice were sold. From a Jewish point of view there was nothing wrong with either of these activities. The popular idea that Jesus objected to “money changing” in the Temple is incorrect. Jews from all over the world brought coinage of all types as offerings to the Temple and it was necessary to have some standard of evaluation and conversion. There was also a need for people to be able to purchase sacrificial animals right at the Temple rather than to try to bring them from afar—especially at Passover when hundreds of thousands of pilgrims required one lamb per household. Some have assumed that the money changing had to do with converting coins with “pagan” images and slogans to Jewish coinage that was considered religiously acceptable. The very opposite was the case. The only coins accepted at the Jerusalem Temple were silver Tyrian shekels and half-shekels, which had the image of Hercules on one side and an eagle perched on the bow of a ship on the other! The issue was not pagan images but consistency of value. Tyrian shekels were guaranteed to be made of 95 percent pure silver. The Sadducean priests who ran the Temple conveniently argued that the “purity” of one’s offering to God superseded any defilement that the images might bring.

At Passover the money-changing operation was vastly expanded since Moses had commanded that each male Jew over the age of twenty donate a half-shekel of silver to the sanctuary once a year (Exodus 30:13). This offering, due by Passover, necessitated special tables to be set up in the Temple three weeks before to handle the huge crowds who would come to Jerusalem for the festival. Josephus estimates that two and a half million Jews from all around the world gathered in Jerusalem at Passover. He based his number on the 225,600 lambs that were sacrificed on the day of Passover itself. Scholars find his numbers likely inflated, but even with that taken into consideration the task of handling the numbers of Passover pilgrims must have been staggering.

The profit from these activities was enormous. The Jerusalem Temple had the most lucrative system of temple commerce in the entire Roman world. As one might expect, there were certain fees and surcharges added to these services. These funds went to support the wealthy class of Sadducean priests who had their lavish homes just west of the Temple compound in the area today called the “Jewish Quarter” as well as on the slopes of Mt Zion, as our recent excavations have shown, see here. These priests in turn worked closely with their Roman sponsors. To understand the economy in Jerusalem, which really was a type of “Temple state,” one needs only to “follow the money.”

But what about the poor or those who could scarcely afford the trip to Jerusalem, much less the inflated charges for these required sacrifices? Maybe Jesus had been told the story growing up of how his mother Mary and his adopted father Joseph had not even been able to afford a lamb for an offering at his birth. They had managed to purchase two doves. And somehow they had to come up with the five Tyrian silver shekels to fulfill the commandment of “redeeming the firstborn.” Jesus’ family was typical of thousands of others at the time—large, poor, and yet devoted to fulfilling God’s commandments.

Jesus arrived that Monday morning at the very height of the trade season. He had three words on his mind: Zechariah, Isaiah, and Jeremiah. At the very end of Zechariah’s sequential scenario of the “end times” he declares, “And there will no longer be traders in the house of Yahweh of hosts on that day” (Zechariah 14:21). Jeremiah had gone into the Temple of his day, the 1st Temple built by King Solomon, and declared in the name of Yahweh: “Has this house, which is called by my name, become a den of robbers in your sight?” (Jeremiah 7:11). And Isaiah had envisioned a time when God’s Temple at Jerusalem would become a “house of prayer for all nations,” providing a spiritual center for humanity (Isaiah 56:7).

Jesus’ activities that day were not intended to change things or to spark a revolution. Like his ride down the Mount of Olives on the foal of the donkey, he intended to signal something—namely that the imminent overthrow of the corrupt Temple system was at hand and the vision of the Prophets would be fulfilled. He began to overturn the tables of the money changers and topple the pay stations of those who sat taking money for the sale of the animals. He then quoted the words of Jeremiah and Isaiah as an explanation for his actions. Mark also adds that he “would not allow anyone to carry anything through the Temple”

(Mark 11:16). There were certain narrow gates through which goods had to pass to support the exchange and sales activities and Jesus stationed several of his rugged Galilean men at these posts and told them business was closed for the day.

The priestly leadership heard about the ruckus. They already had been looking for a way to have Jesus arrested and killed. They were more determined than ever to stop him but they feared the people. The crowd must have been immense that Monday morning and the crush of people cheered on Jesus. This was not a riot for which the priests might call in the Romans. They would be reluctant to do that anyway since the governor Pontius Pilate was known for his brutal handling of Temple crowds and his disdain for the Jews in general. Jesus’ actions were a symbolic “prophetic protest” and he had the support of the people, who were likely tired of paying the prices demanded to fulfill these ritual requirements. Mark indicates the “siege” lasted the entire day and it was only at evening that Jesus and his men left the city and went back to Bethany for the night.

Tuesday was an important day for Jesus and his Council of Twelve. They openly went back to the Temple early that morning and Jesus spent the entire day verbally sparring with various segments of the Temple establishment, including the Sadducean priests, leading Pharisees, and the Herodians—the political supporters of Herod’s dynasty. The priests asked him “by what authority are you doing these things?” They apparently referred to his two “prophetic” activities on Sunday and Monday. He said he would tell them if they would state in front of the crowds who were intently following the exchange whether John the Baptizer had been a prophet of God or a charlatan. Although the priests had not responded positively to John’s call of repentance and baptism, the people had, by the masses, and the priests feared to answer, knowing John’s immense popularity. The Pharisees and Herodians asked Jesus whether he supported Roman taxation—perhaps the most sensitive political and religious issue of the day. Holding up a Roman coin he replied with his now famous but ambiguous retort: “Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s and to God the things that are God’s” (Mark 12:17).

Jesus said two things that day that seem to epitomize his entire view of “true religion,” especially vis-à-vis what was going on in the Herodian Temple. A man asked Jesus which of the commandments of the Torah was the greatest. Jesus quoted the Shema—that great confession of the Jewish faith: “Hear O Israel, Yahweh our God, Yahweh is One, and you shall love Yahweh your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind, and with all your strength.” He added that the “second” greatest commandment was to love one’s fellow human being as oneself. The man agreed and observed that if one loved God, and loved one’s fellow as oneself, that would be “much more than all whole burnt offerings and sacrifices.” Jesus then made a surprising statement to the man: “You are not far from the Kingdom of God” (Mark 12:28–34). This indicates that Jesus’ view of the Kingdom of God involved not only the revolutionary overthrow of the kingdoms of the world, but also a certain spiritual insight into what God most desires from human beings. One would not be complete without the other.

Toward the end of the day, as people were lined up to bring their monetary contributions into the Temple treasury, Jesus observed a poor widow who had come with two copper coins. It was all she had. He told the crowds, “This poor widow has put in more than all of these” (Mark 12:43). The coin was called a lepton and it took one hundred of them to make a denarius—an average day’s wage for a laborer.

Throughout the day the crowds were amazed and thrilled at all Jesus said and they marveled at the way he seemed to be able to handle his challengers no matter their rank or power. The gospels report repeatedly that Jesus’ enemies wanted to arrest him but feared the crowds. Luke says that people were pouring into the Temple to hear him as word spread through the city about the excitement he had caused (Luke 21:38). The Temple officials knew that if they acted publicly they would provoke a riot among the people and the Romans would step in, possibly blaming them for the disturbance. Their only hope was to arrest Jesus somehow when he was alone, maybe at night, with only a few of his followers around. Passover was two days away and they had no idea what Jesus had in mind or of what he might be capable. They determined that they had to act fast, and before the festival of Passover that began Wednesday evening. The next 48 hours proved critical.

To Be Continued…

Comments are closed.