Subscribe to TaborBlog in the Sidebar and don’t miss a single post.

Today I begin a series of posts on “James the Just,” the largely forgotten brother of Jesus, following up on my post “Another Comforter: The Forgotten Brother of Jesus” on the missing key to understanding Christian origins. [1]Robert Eisenman, in his pioneering 1997 book, James the Brother of Jesus, laid out the foundations for a recovery of “the historical James,” see Robert Price’s review here as well as an … Continue reading

The disciples said to Jesus, “We know you will leave us. Who is going to be our leader then?” Jesus said to them, “No matter where you go you are to go to James the Just, for whose sake heaven and earth came into being.” (Gospel of Thomas 12)

When the charismatic leader of a movement is violently killed one expects chaos, confusion, and disintegration to follow. Josephus, our 1st century Jewish historian, mentioned at least a dozen other messianic aspirants and revolt leaders whom the Romans executed during the late 2nd Temple period. In each case the movements they started were crushed or faded away. There was clearly something different about the Jesus movement. After all, they had lost both their leaders, first John the Baptist and then Jesus, both of whom they considered “Messiahs,” and in whom there was so much hope (see “Waiting for Two Messiahs“). But the movement did not die out; in fact it began to grow and spread.

The traditional view is that Jesus appeared in resurrected glory the Sunday after his Friday crucifixion turning his death into celebration and triumph. This is what Christians celebrate at Easter. But if Jesus truly died, and was buried, and his family and followers no longer had him physically present, and they went through a period of horrible grief and loss, as a more historical reading of the evidence suggests, how was it that the movement survived at all? As I have discussed in a previous post titled, “What Really Happened Easter Morning,” (which I recommend you read first if you have not) there is an alternative tradition preserved in the gospel of John, in the very last chapter, as if it is tacked on. There we read that Peter and several of the Twelve returned to their fishing nets in Galilee, resuming a normal life for a time. The Gospel of Peter knows of this tradition as well, and offers more details, telling us that the disciples spent the entire eight days of Passover weeping and mourning, following which they returned to Galilee and went back to their fishing business. They clearly have had no “Easter” experience. This sounds more like what one might expect. So what accounted for the transformation from despair to hope and renewal of faith?

I would attribute the survival and the revival of the Jesus movement to three factors.

First, there is James himself, as well as Jesus’ mother and brothers. Jesus was gone but James, as we will see, became a towering figure of faith and strength for Jesus’ followers, as I discussed in the post yesterday. To have Jesus’ own brother with them, his own flesh and blood, and one who also shared Jesus’ royal Davidic lineage, had to have been a powerful reinforcement. And this would be the case with Jesus’ family as a whole. They became the anchor of his movement. Mary has been revered for her role as the “Mother of God” for centuries, but historically speaking, her role as the very human mother of this extraordinary family of six sons and two daughters seems to have been lost. Unfortunately, we don’t have many details about how James was able to accomplish what he did as leader of the movement. As we will see, his role has been almost totally marginalized in our New Testament records, but the results are evident. He was known as “James the Less,” which I take to mean “James the Younger,” possibly indicating he was a young man when he took over following his brother’s death, see here. He must have grown into the role with time, as he matured into a man who earned the respect of his contemporaries.

A second factor was the message that both John and Jesus had preached, the “good news of the Kingdom of God” and all that it implied. However revered the messengers might have been, what they advocated and proclaimed lived on and was in no way destroyed or lost by their deaths. They had spoken out against injustice and oppression, they had issued a call for repentance and proclaimed forgiveness of sins, and they embodied the messianic hope and faith rooted in the Hebrew Prophets. The cause of the Two Messiahs–John and Jesus–remained and survived.

Jesus and John had proclaimed that the “end of the age” had drawn near. The apocalyptic perspective that they embodied was reinforced, as we shall see, by the social and political events of their time. It was as if all that the Hebrew Prophets had predicted was in the process of being fulfilled before their eyes. The instability in Rome, the threat of wars and revolt, and even the opposition they faced from the authorities were all seen as further signs that the “appointed time” had grown very short—just as Jesus had proclaimed. They were an intensely apocalyptic community that expected to see the Kingdom of God manifested in its fullness.

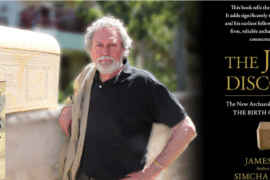

Finally, the community believed that Jesus, though crucified and buried, had been exalted to the heavens, vindicated by God as his Messiah. This faith in Jesus’ heavenly exaltation turned their despair into a sense of vindication and victory. The latest evidence in the Talpiot “patio” tomb, with the inscription about God “lifting up” from the dead, as well as the Jonah image, reinforces this understanding of the earliest Christian resurrection hope, see my post here, as well as the complete presentation in the book, The Jesus Discovery.

Jesus had expected the arrival of the “Son of Man” even before his death. When he had sent out the Twelve he had told them that they would not have “gone through all the towns of Israel before the Son of Man comes.” In Daniel’s dream the “coming of the Son of Man in the clouds of heaven” was a symbol for the time when the people of God would be given rule over all the nations (Daniel 7:13–14, 27). It was only later made to refer exclusively to Jesus himself, as an individual. Jesus had declared that his casting out of demons was a sure sign that the “kingdom of God had arrived”; he compared this work to storming the fortress of a “strong man,” namely Satan, and overpowering him (Luke 11:20–22). Jesus’ death was surely a terrible shock to all who loved and followed him, but they continued to believe fervently in the central message that both Jesus and John the Baptizer before him had proclaimed: “Repent, for the Kingdom of God is at hand.”

The main body of Jesus’ core followers, including those who had been with the Messianic Movement from the time John the Baptizer had begun his work, gathered in Jerusalem in the late spring as summer neared. The festival of Pentecost or Shavuot fell the last week of May that year. There were not too many left, just over a hundred who had stayed loyal through the dark and trying days of Passover (Acts 1:15). The guest house with the “Upper Room” where Jesus had eaten his last meal became their center of operations. Bargil Pixner has offered what I consider to be convincing evidence that this house was located on what is today called Mt Zion, and subsequently became the “Church of the Apostles,” the headquarters of the movement, see his Biblical Archaeology Review article here.

The choice of location might have been more than a matter of convenience. Jesus had deliberately chosen that area of the city for his final meeting with the Twelve. King David had written a Psalm where God declared “I will set my king on Zion, my holy hill,” referring to “Mount Zion” (Psalms 2:6). According to Josephus this was the area of the tomb of David, which might explain the reference of Peter to the tomb “being with us to this day” (Acts 2:29). Since many were from Galilee and other areas of the country, the community pooled their resources and began to live a loosely communal life, sharing their meals together, with those from out of town staying in the homes of those who lived in Jerusalem (Acts 2:46). There must have been a sense of danger but also one of excited expectation—since surely God would not allow the death of his Righteous Ones, John and Jesus, to go unpunished. Shortly before the day of Pentecost the group gathered to deliberate their situation. They needed a new leader and had to replace Judas Iscariot on the Council of Twelve.

What happened next is one of the greatest “untold” stories of the past two millennia. The tradition most people remember is that the apostle Peter took over leadership of the movement as head of the Twelve. He and the fisherman John, whom later tradition transformed into Jesus’ “Beloved Disciple,” (completely bypassing James the brother of Jesus, see “Who Was the Mysterious Disciple Whom Jesus Loved?”), according to the author of the book of Acts take the leadership of the group (Acts 3:1-11; 4:13-19; 8:14). But we know from Paul’s much earlier and more accurate testimony that Peter and John were basically envoys of James the brother of Jesus, who was clearly in charge, whom the author of Acts conveniently leaves out of the narratives (see Galatians 2:9-12).

According to this version of the story, not long after Paul, newly converted to the Christian faith from “Judaism,” joined Peter’s side. Together, the apostles Peter and Paul became the twin “pillars” of the emerging Christian faith, preaching the gospel to the entire Roman world and dying gloriously as martyrs in Rome—the new divinely appointed headquarters of the Church. This view of things has been enshrined in Christian art through the ages as well as popularized in books and films. Indeed, Peter’s primacy as the first pope has even become the cornerstone of Roman Catholic dogmatic teaching. Standing in Vatican city, in the courtyard of the Basilica of St. Peter, we see the towering statues of Peter to the left and Paul to the right, on each side of the majestic stairway leading inside, with James nowhere to be seen. After all, given the later doctrines of the “perpetual virginity of Mary” as “mother of God,” the idea that Jesus even had any brothers and sisters became heresy, see my post “Mary–Mother of God or Jewish Mother of Seven.”

We now know that things did not happen this way. Peter did rise to prominence in the group of the Twelve, as we shall see, but it was James the brother of Jesus who became the successor to Jesus and the undisputed leader of the Christian movement.

Jesus, their Davidic ruler, had been removed from their midst. James was next in the royal Davidic bloodline. Jesus’ death was not the end of the movement politically or spiritually. The Jesus dynasty would continue for over a century after his death. But if this is the case, how could James, the heir to the Jesus dynasty, have been almost entirely left out of the story

of Christian origins—and more important—why? James hardly even appears in Christian art and iconography. It is as if his very existence has been all but forgotten. But he emerges in a history hidden from view. This history, which we will explore in this series of posts, is a startling and inspiring story with important implications for our understanding of Jesus and the cause for which he lived and died.

Part 2 is here. For a complete treatment of this subject, with full notes and sources, see my book, The Jesus Dynasty.

Comments are closed.