From more of this story read my book The Jesus Dynasty, available at discount prices and in all formats–Kindle, iBook, Nook, CD Audio, which also has notes and references to this material.

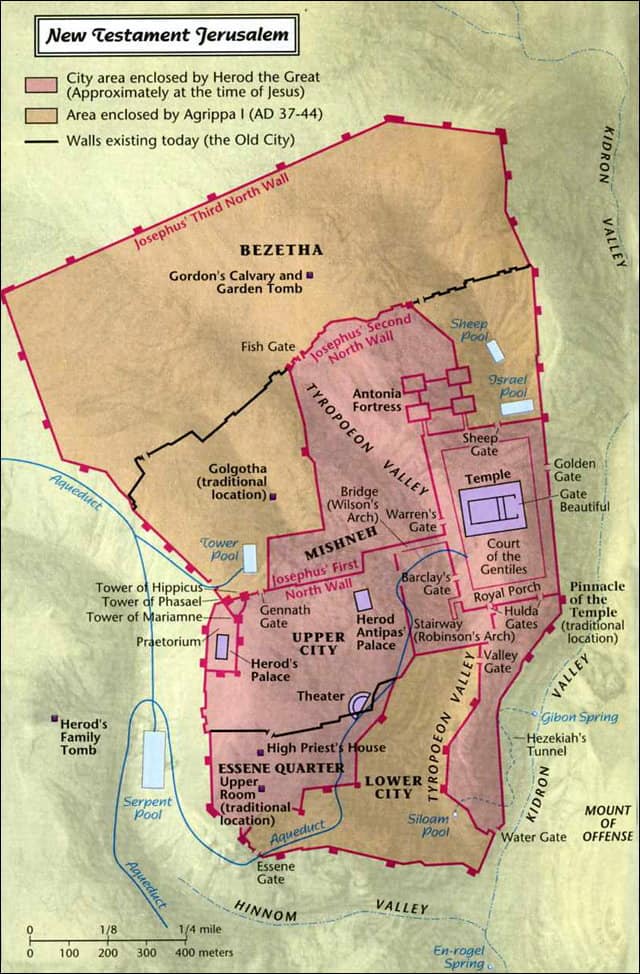

On Wednesday Jesus began to make plans for Passover. He sent two of his disciples into the city to prepare a large second-story guest room where he could gather secretly and safely with his inner group. He knew someone with such a room available and he had prearranged for its use. Christian pilgrims today are shown a Crusader site known as the Cenacle or “Upper Room” on the Western Hill of Jerusalem that the Crusaders misnamed “Mount Zion.” This area was part of the “Upper City” where Herod had built his palace. It is topographically higher than even the Temple Mount. It was the grandest section of ancient Jerusalem with broad streets and plazas and the palatial homes of the wealthy. Bargil Pixner and others have also argued that the southwest edge of Mt Zion contained an “Essene Quarter,” with more modest dwellings and its own “Essene” Gate mentioned by Josephus, see his article “Jerusalem’s Essene Gateway,” here.

Jesus tells his two disciples to “follow a man carrying a jug of water,” who will enter the city, and then enter a certain house. The only water source was in the southern part of the lower city of Jerusalem, the recently uncovered Pool of Siloam. This mysterious man apparently walked up the slope of Mt Zion and entered the city–likely at the Essene Gate. The house is large enough to have an upper story and likely belonged to a wealthy sympathizer of Jesus, perhaps associated with the Essenes. Later this property became the HQ of the Jesus movement led by James the brother of Jesus, see Pixner’s article “The Church of the Apostles Found on Mt Zion” here.

Later Christian tradition put Jesus’ last meal with his disciples on Thursday evening and his crucifixion on Friday. We now know that is one day off. Jesus’ last meal was Wednesday night, and he was crucified on Thursday, the 14th of the Jewish month Nisan. The Passover meal itself was eaten Thursday night, at sundown, as the 15th of Nisan began. Jesus never ate that Passover meal. He had died at 3 p.m. on Thursday.

The confusion arose because all the gospels say that there was a rush to get his body off the cross and buried before sundown because the “Sabbath” was near. Everyone assumed the reference to the Sabbath had to be Saturday—so the crucifixion must have been on a Friday. However, as Jews know, the day of Passover itself is also a “Sabbath” or rest day—no matter what weekday it falls on. In the year a.d. 30, Friday the 15th of the Nisan was also a Sabbath—so two Sabbaths occurred back to back—Friday and Saturday. Matthew seems to know this as he says that the women who visited Jesus’ tomb came early Sunday morning “after the Sabbaths”—the original Greek is plural (Matthew 28:1).

As is often the case, the gospel of John preserves a more accurate chronology of what went on. John specifies that the Wednesday night “last supper” was “before the festival of Passover.” He also notes that when Jesus’ accusers delivered him to be crucified on Thursday morning they would not enter Pilate’s courtyard because they would be defiled and would not be able to eat the Passover that evening (John 18:28). John knows that the Jews would be eating their traditional Passover, or Seder meal, Thursday evening.

Reading Mark, Matthew, and Luke one can get the impression that the “last supper” was the Passover meal. Some have even argued that Jesus might have eaten the Passover meal a day early—knowing ahead of time that he would be dead. But the fact is, Jesus ate no Passover meal in 30 CE. When the Passover meal began at sundown on Thursday, Jesus was dead. He had been hastily put in a tomb until after the festival

when a proper funeral could be arranged.

There are some hints outside of John’s gospel that such was the case. In Luke, for example, Jesus tells his followers at that last meal: “I earnestly wanted to eat this Passover with you before I suffer but I won’t eat it until it is fulfilled in the kingdom of God” (Luke 22:14–16). A later copyist of the manuscript inserted the word “again” to make it say “I won’t eat it again,” since the tradition had developed that Jesus did observe Passover that night and changed its observance to the Christian Eucharist or Mass. Another indication that this is not a Passover meal is that all our records report that Jesus shared “a loaf of bread” with his disciples, using the Greek word (artos) that refers to an ordinary loaf—not to the unleavened flatbread or matzos that Jews eat with their Passover meals. Also, when Paul refers to the “last supper” he significantly does not say “on the night of Passover,” but rather “on the night Jesus was betrayed,” and he also mentions the “loaf of bread” (1 Corinthians 11:23). If this meal had been the Passover, Paul would have surely wanted to say that, but he does not.

As late as Wednesday morning Jesus had still intended to eat the Passover on Thursday night. When he sent his two disciples into the city he instructed them to begin to make the preparations. His enemies had determined not to try to arrest him during the feast “lest there be a riot of the people” (Mark 14:2). That meant he was likely “safe” for the next week, since the “feast” included the seven days of Unleavened Bread that followed the Passover meal. Passover is the most family-oriented festival in Jewish tradition. As head of his household Jesus would have gathered with his mother, his sisters, the women who had come with him from Galilee, perhaps some of his close supporters in Jerusalem, and his Council of Twelve. It is inconceivable that a Jewish head of a household would eat the Passover segregated from his family with twelve male disciples. This was no Passover meal. Something had gone terribly wrong so that all his Passover plans were changed.

Jesus had planned a special meal Wednesday evening alone with his Council of Twelve in the upper room of the guesthouse in the lower city. The events of the past few days had brought things to a crisis and he knew the confrontation with the authorities was unavoidable. In the coming days he expected to be arrested, delivered to the Romans, and possibly crucified. He had intentionally chosen the time and the place—Passover in Jerusalem—to confront the powers that be. There was much of a private nature to discuss with those upon whom he most depended in the critical days ahead. He firmly believed that if he and his followers offered themselves up, placing their fate in God’s hands, that the Kingdom of God would manifest itself. He had intentionally fulfilled two of Zechariah’s prophecies—riding into the city as King on the foal, and symbolically removing the “traders” from the “house of God.”

At some point that day Jesus had learned that Judas Iscariot, one of his trusted Council of Twelve, had struck a deal with his enemies to have Jesus arrested whenever there was an opportunity to get him alone, away from the crowds. How Jesus knew of the plot we are not told but during the meal he said openly, “One of you who is eating with me will betray me” (Mark 14:18). His life seemed to be unfolding according to some scriptural plan. Had not David written in the Psalms, “Even my bosom friend, in whom I trusted, who ate of my bread, has lifted the heel against me” (Psalm 41:9). History has a strange way of repeating itself. Over a hundred years earlier, the Teacher of Righteousness who led the Dead Sea Scroll community had quoted that very Psalm when one of his inner “Council” had betrayed him.

When Judas Iscariot realized that the plan for the evening included a retreat for prayer in the Garden of Gethsemane after the meal, he abruptly left the group. This secluded spot, at the foot of the Mount of Olives, just across the Kidron Valley from the Old City, offered just the setting he had promised to deliver. Some have tried to interpret Judas’s motives in a positive light. Perhaps he quite sincerely wanted Jesus to declare himself King and take power, thinking the threat of an arrest might force his hand. We simply don’t know what might have been in his mind. The gospels are content simply to call him “the Betrayer” and his name is seldom mentioned without this description.

Ironically our earliest account of that last meal on Wednesday night comes from Paul, not from any of our gospels. In a letter to his followers in the Greek city of Corinth, written around a.d. 54, Paul passes on a tradition that he says he “received” from Jesus: “Jesus on the night he was betrayed took a loaf of bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it and said, ‘This is my body that is broken for you. Do this in remembrance of me.’ In the same way he took the cup also, after supper, saying, ‘This cup is the new covenant in my blood. Do this, as often as you drink it, in remembrance of me’ ” (1 Corinthians 11:23–25).

These words, which are familiar to Christians as part of the Eucharist or the Mass, are repeated with only slight variations in Mark, Matthew, and Luke. They represent the epitome of Christian faith, the pillar of the Christian Gospel: all humankind is saved from sins by the sacrificed body and blood of Jesus. What is the historical likelihood that this tradition, based on what Paul said he “received” from Jesus, represents what Jesus said at that last meal? As surprising as it might sound, there are some legitimate problems to consider.

At every Jewish meal, bread is broken, wine is shared, and blessings are said over each—but the idea of eating human flesh and drinking blood, even symbolically, is completely alien to Judaism. The Torah specifically forbids the consuming of blood, not just for Israelites but anyone. Noah and his descendants, as representatives of all humanity, were first given the prohibition against “eating blood” (Genesis 9:4). Moses had warned, “If anyone of the house of Israel or the Gentiles who reside among them eats any blood I will set my face against that person who eats blood and will cut that person off from the people” (Leviticus 17:10). James, the brother of Jesus, later mentions this as one of the “necessary requirements” for non-Jews to join the Nazarene community—they are not to eat blood (Acts 15:20). These restrictions concern the blood of animals. Consuming human flesh and blood was not forbidden, it was simply inconceivable. This general sensitivity to the very idea of “drinking blood” precludes the likelihood that Jesus would have used such symbols.

The Essene community at Qumran described in one of its scrolls a “messianic banquet” of the future at which the Priestly Messiah and the Davidic Messiah sit together with the community and bless their sacred meal of bread and wine, passing it to the community of believers, as a celebration of the Kingdom of God. They would surely have been appalled at any symbolism suggesting the bread was human flesh and the wine was blood. Such an idea simply could not have come from Jesus as a Jew.

So where does this language originate? If it first surfaces in Paul, and he did not in fact get it from Jesus, then what was its source? The closest parallels are certain Greco-Roman magical rites. We have a Greek papyrus that records a love spell in which a male pronounces certain incantations over a cup of wine that represents the blood that the Egyptian god Osiris had given to his consort Isis to make her feel love for him. When his lover drinks the wine, she symbolically unites with her beloved by consuming his blood. In another text the wine is made into the flesh of Osiris. The symbolic eating of “flesh” and drinking of “blood” was a magical rite of union in Greco-Roman culture.

We have to consider that Paul grew up in the Greco-Roman culture of the city of Tarsus in Asia Minor, outside the land of Israel. He never met or talked to Jesus. The connection he claims to Jesus is a “visionary” one, not Jesus as a flesh-and-blood human being walking the earth. See my book, Paul and Jesus for a full elaboration of the implications of Paul’s visionary revelations. When the Twelve met to replace Judas, after Jesus had been killed, they insisted that to be part of their group one had to have been with Jesus from the time of John the Baptizer through his crucifixion (Acts 1:21–22). Seeing visions and hearing voices were not accepted as qualifications for an apostle.

Second, and even more telling, the gospel of John recounts the events of that last Wednesday night meal but there is absolutely no reference to these words of Jesus instituting this new ceremony of the Eucharist. If Jesus in fact had inaugurated the practice of eating bread as his body, and drinking wine as his blood at this “last supper” how could John possibly have left it out? What John writes is that Jesus sat down to the supper, by all indications an ordinary Jewish meal. After supper he got up, took a basin of water and a cloth, and began to wash his disciples’ feet as an example of how a Teacher and Master should act as a servant—even to his disciples. Jesus then began to talk about how he was to be betrayed and John tells us that Judas abruptly left the meal.

Mark’s gospel is very close in its theological ideas to those of Paul. It seems likely that Mark, writing a decade after Paul’s account of the last supper, inserts this “eat my body” and “drink my blood” tradition into his gospel, influenced by what Paul has claimed to have received. Matthew and Luke both base their narratives wholly upon Mark, and Luke is an unabashed advocate of Paul as well. Everything seems to trace back to Paul. As we will see, there is no evidence that the original Jewish followers of Jesus, led by Jesus’ brother James, headquartered in Jerusalem, ever practiced any rite of this type. Like all Jews they did sanctify wine and bread as part of a sacred meal, and they likely looked back to the “night he was betrayed,” remembering that last meal with Jesus.

What we really need to resolve this matter is an independent source of some type, one that is Christian but not influenced by Paul, that might shed light on the original practice of Jesus’ followers. Fortunately, in 1873 in a library at Constantinople, just such a text turned up. It is called the Didache and dates to the early 2nd century CE. It had been mentioned by early church writers but had disappeared until a Greek priest, Father Bryennios, discovered it in an archive of old manuscripts quite by accident. The title Didache in Greek means “Teaching” and its full title is “The Teaching of the Twelve Apostles.” It is a type of early Christian “instruction manual” probably written for candidates for Christian baptism to study. It has lots of ethical instructions and exhortations but also sections on baptism and the Eucharist—the sacred meal of bread and wine. And that is where the surprise comes. It offers the following blessings over wine and bread:

With respect to the Eucharist you shall give thanks as follows. First with respect to the cup: “We give you thanks our Father for the holy vine of David, your child which you made known to us through Jesus your child. To you be the glory forever.” And with respect to the bread: “We give you thanks our Father for the life and knowledge that you made known to us through Jesus your child. To you be the glory forever.”

Notice there is no mention of the wine representing blood or the bread representing flesh. And yet this is a record of the early Christian Eucharist meal! This text reminds us very much of the descriptions of the sacred messianic meal in the Dead Sea Scrolls. Here we have a messianic celebration of Jesus as the Davidic Messiah and the life and knowledge that he has brought to the community. Evidently this community of Jesus’ followers knew nothing about the ceremony that Paul advocates. If Paul’s practice had truly come from Jesus surely this text would have included it.

There is another important point in this regard. In Jewish tradition it is the cup of wine that is blessed first, then the bread. That is the order we find here in the Didache. But in Paul’s account of the “Lord’s Supper” he has Jesus bless the bread first, then the cup of wine—just the reverse. It might seem an unimportant detail until one examines Luke’s account of the words of Jesus at the meal. Although he basically follows the tradition from Paul, unlike Paul Luke reports first a cup of wine, then the bread, and then another cup of wine! The bread and the second cup of wine he interprets as the “body” and “blood” of Jesus. But with respect to the first cup—in the order one would expect from Jewish tradition—there is nothing said about it representing “blood.” Rather Jesus says, “I tell you that from now on I will not drink of the fruit of the vine until the kingdom comes” (Luke 22:18). This tradition of the first cup, found now only in Luke, is a leftover clue of what must have been the original tradition before the Pauline version was inserted, now confirmed by the Didache.

Understood in this light, this last meal makes historical sense. Jesus told his closest followers, gathered in secret in the Upper Room, that he will not share another meal with them until the Kingdom of God comes. He knows that Judas will initiate events that very night, leading to his arrest. His hope and prayer is that the next time they sit down together to eat, giving the traditional Jewish blessing over wine and bread—the Kingdom of God will have come.

Since Jesus met only with his Council of Twelve for that final private meal, then James as well as Jesus’ other three brothers would have been present. This is confirmed in a lost text called the Gospel of the Hebrews that was used by Jewish-Christians who rejected Paul’s teachings and authority. It survives only in a few quotations that were preserved by Christian writers such as Jerome. In one passage we are told that James the brother of Jesus, after drinking from the cup Jesus passed around, pledged that he too would not eat or drink again until he saw the kingdom arrive. So here we have textual evidence of a tradition that remembers James as being present at the last meal.

In the gospel of John there are cryptic references to James. Half a dozen times John mentions a mysterious unnamed figure that he calls “the disciple whom Jesus loved.” The two are very close; in fact this unnamed disciple is seated next to Jesus either at his right or left hand. He leaned back and put his head on Jesus’ breast during the meal (John 13:23). He is the one to whom Jesus whispers that Judas is the betrayer. Even though tradition holds that this is John the fisherman, one of the sons of Zebedee, it makes much better sense that such intimacy was shared between Jesus and his younger brother James. After all, from the few stories we have about John son of Zebedee, he has a fiery and ambitious personality—Jesus had nicknamed him and his brother the “sons of Thunder.” They are the two that had tried to obtain the two chief seats on the Council of Twelve, one asking for the right hand, the other the left. On another occasion they asked Jesus for permission to call down fire from heaven to consume a village that had not accepted their preaching (Luke 9:54). On both occasions Jesus had rebuked them. The image we get of John son of Zebedee is quite opposite from the tender intimacy of the “disciple whom Jesus loved.” No matter how ingrained the image might be in Christian imagination, it makes no sense to imagine John son of Zebedee seated next to Jesus, and leaning on his breast.

It seems to me that the evidence points to James the brother of Jesus being the most likely candidate for this mysterious unnamed disciple. Later, just before Jesus’ death, the gospel of John tells us that Jesus put the care of his mother into the hands of this “disciple whom he loved” (John 19:26–27). How could this possibly be anyone other than James his brother, who was now to take charge of the family as head of the household?

Late that night, after the meal and its conversations, Jesus led his band of eleven disciples outside the lower city, across the Kidron Valley, to a thick secluded grove of olive trees called Gethsemane at the foot of the Mount of Olives. Judas knew the place well because Jesus often used it as a place of solitude and privacy to meet with his disciples (John 18:2). Judas had gone into the city to alert the authorities of this rare opportunity to confront Jesus at night and away from the crowds.

It was getting late and Jesus’ disciples were tired and drowsy. Sleep was the last thing on Jesus’ mind, and he was never to sleep again. His all-night ordeal was about to begin. He began to feel very distressed, fearful, and deeply grieved. He wanted to pray for strength for the trials that he knew would soon begin. Mark tells us that he prayed that if possible the “cup would be removed from him” (Mark 14:36). Jesus urged his disciples to pray with him but the meal, the wine, and the late hour took their toll. They all fell asleep.

Comments are closed.