I want to share an amazing story.

Not too long after the publication of my book The Jesus Dynasty in April, 2006 I was told about an English professor at the University of Arkansas who had recently died who had done a wealth of research on Pantera, had traveled to Germany to study the Pantera tombstone, and had a treasure of unpublished material. I was interested but since she did not know the professor’s name or any more details I more or less put the story out of my mind.

Later that year I conducted a Biblical Archaeology Seminar in Austin, Texas on “Lost Christianities,” with Profs. April DeConick of Rice University, and Charles Hedrick at Missouri State University. One of my lectures dealt with the “Pantera” tradition. It was a kind of “state of the question” report on what we can say from an historical perspective on the subject. I could have never imagined what happened next.

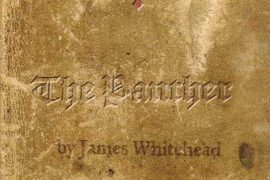

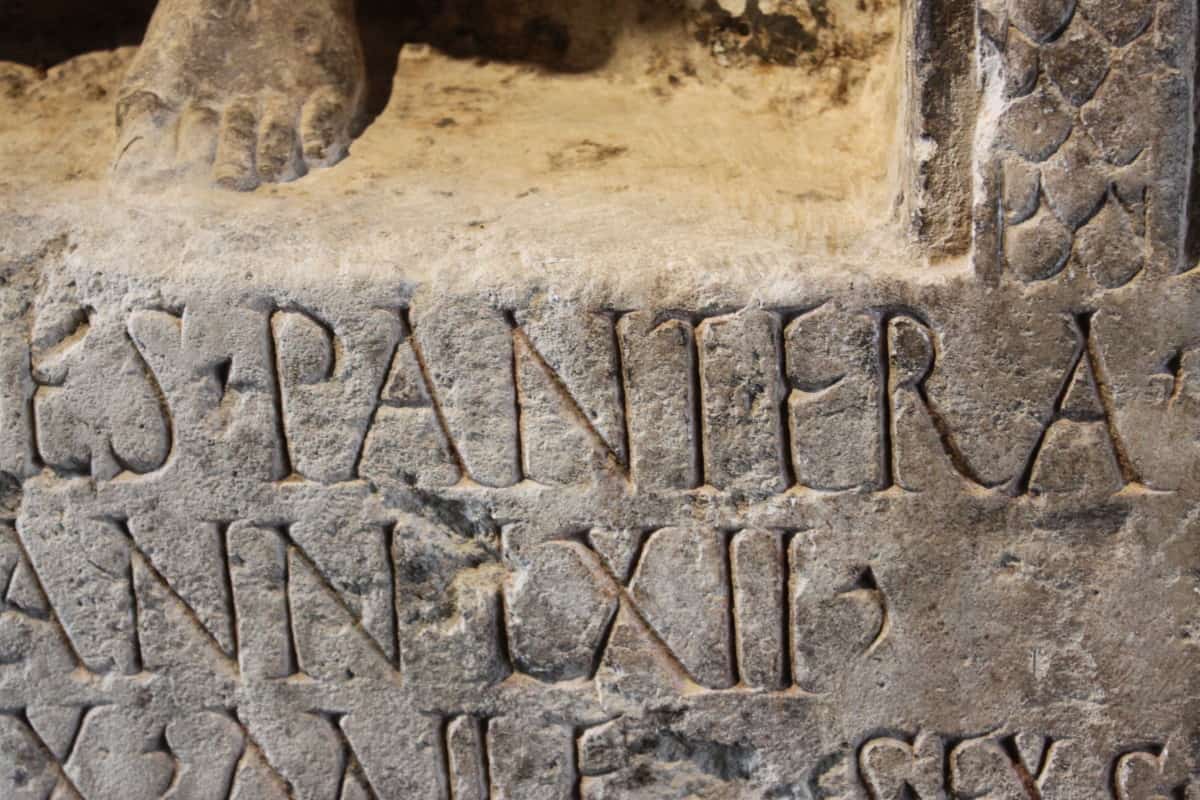

When Hedrick returned to Missouri State University he mentioned my book and my Pantera lecture to a colleague of his in the English department–one Michael Burns, a poet. He recalled that Burns had mentioned Pantera a few times. As it turns out, Burns had been a student of another poet, James Whitehead, at the University of Arkansas, who had died in August, 2003. In his later years, Whitehead, an accomplished poet and novelist (author of the 1971 bestseller Joiner), had become fascinated with the Pantera legend. He had come across it in Morton Smith’s 1978 book, Jesus the Magician, in which Smith comments on the Pantera tombstone in Germany, making the passing suggestion, partly tongue-in-cheek, that it is possible, though not likely, that this tombstone might be our only “genuine relic of the Holy Family” (p. 47).

Whitehead’s imagination was fired by the idea that the young Mary might have loved and become pregnant from this young man from Palestine who ended up a Roman soldier dying at age 62 on the German frontier. He traveled to Germany to visit the tombstone and contacted a couple of young German archaeologists, Peter Haupt and Sabine Hornung, who guided him in his research. Whitehead ended up writing an entire series of poems on “The Panther,” as he affectionately called his protagonist. He was also working on a dramatic documentary about his own Quest that had taken him to Germany.

Imagine my surprise when I received an e-mail “out of the blue” from Michael Burns in late September. Burns told me the story of his late mentor James Whitehead, of Whitehead’s passion for the Mary and Pantera story, and he offered to let me look at both the poems and the drama. When I received copies a few days later I was totally “blown away” and deeply impressed by Whitehead’s work. He had somehow captured in his skillful poetic imagination a version of this ‘greatest love story never told,” that was historically plausible and profoundly moving.

Over the next few months I learned much more about James Whitehead and the illustrious poetic circles at the University of Arkansas of which he was a part (Miller Williams, who read at Clinton’s 2nd inaugural was part of that scene). I have spoken with Michael Burns at length, talked to Gen Whitehead Broyles, Whitehead’s widow, and corresponded with Thomas Kennedy, a dear friend and colleague of Whitehead’s who had accompanied him on his trips to Germany.

I will offer an excerpt from the published book of Whitehead poetry in the next post.

Comments are closed.