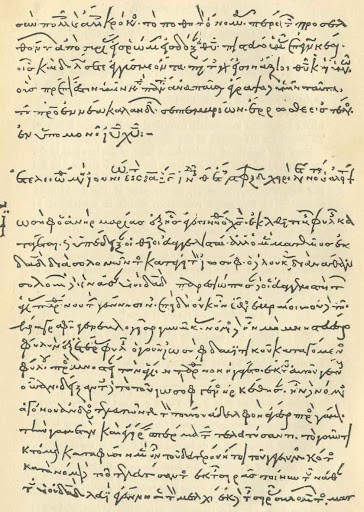

The Didache was discovered in 1873 in a library at Constantinople by a Greek, Priest Father Philoteus Bryennios. This precious text, dating to the late 1st or early 2nd century CE, is mentioned by early Christian writers but had disappeared. Father Bryennios discovered it in an archive of old manuscripts quite by accident. [1]Several English translations are in the public domain and are available on the Web here. I will be using here the new translation by Bart Ehrman, The Apostolic Fathers, Loeb Classical Library 24, … Continue reading

The Didache is divided into sixteen chapters and was intended to be a “handbook” for Christian converts. The first six chapters give a summary of Christian ethics based on the teachings of Jesus, divided into two parts: the way of life and the way of death. Much of the content is similar to what we have in the Sermon on the Mount and the Sermon on the Plain, that is, the basic ethical teachings of Jesus drawn from the Q source now found in Matthew and Luke. It begins with the two “great commandments,” to love God and love one’s neighbor as oneself, as well as a version of the Golden Rule: “And whatever you do not want to happen to you, do not do to another.” It contains many familiar injunctions and exhortations, but often with additions not found in our Gospels:

Bless those who curse you, pray for your enemies, and fast for those who persecute you. (1.3)

If anyone slaps your right cheek, turn the other to him as well and you will be perfect. (1.4)

Give to everyone who asks, and do not ask for anything back,

for the Father wants everyone to be given something from the

gracious gifts he himself provides. (1.5)

Many of the sayings and teachings are not found in our New Testament gospels but are nonetheless consistent with the tradition we know from Jesus and from his brother James:

Let your gift to charity sweat in your hands until you know to whom to give it. (1.6)

Do not be of two minds or speak from both sides of your mouth, for speaking from both sides of your mouth is a deadly trap. (2.4)

Do not be one who reaches out your hands to receive but draws them back from giving. (4.5)

Do not shun a person in need, but share all things with your brother and do not say that anything is your own. (4.8)

Following the ethical exhortations there are four chapters concerning baptism, fasting, prayer, the Eucharist, and the anointing with oil. The Eucharist in the Didache, as I will discuss in a future post, is a simple thanksgiving meal of wine and bread with references to Jesus as the holy “vine of David.” It ends with a prayer: “Hosanna to the God of David,” emphasizing the Davidic lineage of Jesus. There are final chapters on testing prophets and appointing worthy leaders. The last chapter contains warnings about the “last days,” the coming of a final deceiving false prophet, and the resurrection of the righteous who have died. It ends with language similar to that used by Jude, but taken from Zechariah and Daniel: “The Lord will come and all of his holy ones with him” and “Then the world will see the Lord coming on the clouds of the sky.” Both references to the “Lord” here are to Yahweh, the God of Israel.

The entire content and tone of the Didache reminds one strongly of the faith and piety we find in the letter of James, and teachings of Jesus in the Q source. The most remarkable thing about the Didache is that there is nothing in this document that corresponds to Paul’s “gospel”―no divinity of Jesus, no atoning through his body and blood, and no mention of Jesus’ resurrection from the dead. In the Didache Jesus is the one who has brought the knowledge of life and faith, but there is no emphasis whatsoever upon the figure of Jesus apart from his message. Sacrifice and forgiveness of sins in the Didache come through good deeds and a consecrated life (4.6).

The Didache is an precious witness to a form of the Christian faith more directly tied to the Jewish orientation of Jesus’ original followers. I encourage my readers to take a look for themselves. There are many versions both on-line and in print. You can begin here: Early Christian Writings: The Didache.

Comments are closed.