I am often asked a question at lectures and programs that I find hard to answer–“What is your greatest archaeological discovery in the field of Christian Origins?” I have been privileged to be involved in the Tomb of the Shroud in Akeldama, the Suba “John the Baptist” cave, the Talpiot tombs, and several other sites–including my location for Golgotha. If I had to choose I think I would pick what I call “The Jesus Hideout in Jordan.” This one is mine and mine alone. Here is the story.

In 1999, at the very first Biblical Archaeology Society “Bible and Archaeology Fest held that year in Boston, I gave a lecture titled “A Jesus Hideout in Jordan: Texts, Geography, and Archaeology Converge.” If I am not mistaken that lecture has proven to be the most popular of the hundreds I have done in Biblical Archaeology Society Seminars over the past 20 years. I also have uploaded an academic paper, “Wadi el-Yabis and the Elijah “Wadi Cherith” traditions in Relationship to John and Jesus in the Gospel of John,” dealing with the same topic here. This paper, presented at the Society of Biblical Literature annual meeting in 2011, offers the technical underpinnings of my basic theory and proposal. I thought I would offer here a less technical overview of my analysis on this subject.

All our gospels are theological by definition. That is one solid result of the past 100 years of critical-historical work on these texts. However, it has generally been acknowledged that the gospel of John, in contrast to our three Synoptic gospels–Mark, Matthew, and Luke–is the most explicitly theological, especially in the long “red letter” sections where Jesus is represented as giving extended teaching about topics such as the spiritual “birth from above,” receiving eternal life, a spiritual resurrection, his “incarnation,” and mystically consuming his “flesh” and “blood.” Consequently John is usually dated late, even into the 2nd century CE, and he is usually regarded as much further removed from the “historical Jesus” than the Synoptics, and thus less useful for doing serious historical work on Jesus as we might imagine him to have been.

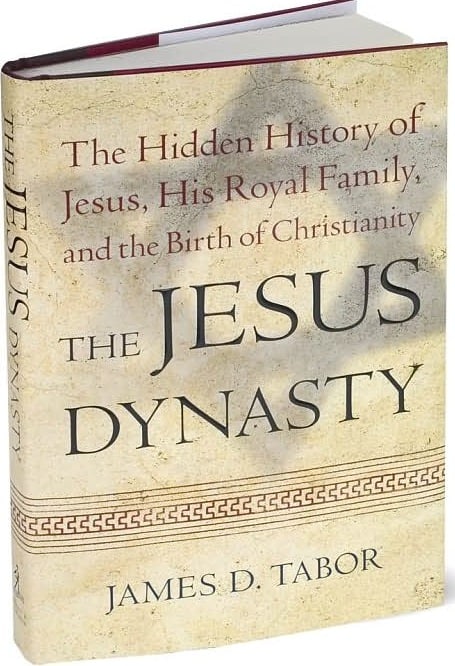

Nonetheless some scholars have begun to reexamine the underlying narrative framework found in the gospel of John. John provides details about both chronology and geography that are most intriguing. In contrast, Mark has few chronological markers, so much so that halfway through his account (chapter 8 of 16 chapters total), Jesus is already on his final journey to Jerusalem where he is crucified. What goes on before that, essentially Jesus’ entire preaching career, narrated in chapters 1-8, is presented in a rapid and sweeping flow of events with no indication as to whether the time involved was days, weeks, months, or even years. In my book, The Jesus Dynasty, I adopted the three and one-half year chronological scheme of the gospel of John (Fall, 26 CE to Spring, 30 CE) and attempted to understand Mark’s fast paced narrative in that light.

I have posted a useful document charting the narrative movement in the gospel of John here on my UNC Charlotte Web site. It is interesting that Mark provides a few “hooks” into John’s framework. The most obvious is the sequence of events with Jesus feeding a crowd, walking on the Sea of Galilee, and teaching in the area of Capernaum, found in Mark 6 and John 6. According to John’s account this is around the time of a 2nd Passover, which would be the spring of the year 29 CE. The most interesting and intriguing of these “hooks,” however, is the short statement in Mark 10:1:

“And he left there (Capernaum) and went to the region of Judea and beyond the Jordan, and crowds gathered to him again; and again, as his custom was, he taught them.”

Until the last week of Jesus’ life when Jesus goes to Jerusalem, Mark sets his entire rapid-paced narrative around the Sea of Galilee, but here he seems to at least be aware of the tradition that we find elaborated in John, that Jesus made these excursion-like forays south to Judea and east beyond the Jordan. Jesus’ move across the Jordan River during the final months of his life is something that really caught my attention in the spring of 1992. I was teaching my standard New Testament/Christian Origins class and we were working through the ending of the gospel of John when these words jumped off the page at me:

“He went away again across the Jordan to the place where John at first baptized, and there he remained. And many came to him…” (John 10:40)

I was showing the students how that verse tied into the one in Mark, and that, according to the gospel of John, Jesus had made a quick trip to Jerusalem at Hanukkah (December, 29 CE), and that Mark at least mentions him going “to the region of Judea” but with no details, but we know from the gospel of John that Jesus’ life was actually in danger and he was in need of a safe place to hide until he decided to make his final moves in Jerusalem the following Spring. But what caught my attention that day was John’s reference to a specific place. I had never noticed that before. I remembered that earlier in his gospel John had actually pinpointed that very place with this description:

“John also was baptizing at Aenon near Salim, because there were many pools there; and people came and were baptized” (John 3:22).

We pulled out the Oxford map of Galilee in the time of Jesus and quickly located Aenon near Salim, just south of Scythopolis, or Beth Shean today. Directly across the Jordan from that spot I noticed two things. There was a “Wadi” or ravine named Cherith, and just to the north the Decapolis town of Pella. Both rang different bells in my head. Cherith, of course, was the ravine where Elijah hid and was fed by the ravens when he fled from king Ahab and queen Jezebel when his life was in danger (1 Kings 18:1-7). And Pella was the traditional location where the followers of Jesus fled around 68 CE when Jerusalem was put under siege by the Romans prior to its destruction. Scholars have always had problems imagining this flight of the Nazarenes, led by Shimon bar Clophas (whom I argue in The Jesus Dynasty is Jesus brother Shimon rather than his cousin), to a pro-Roman Hellenistic city such as Pella and any number have questioned the historical probability of this tradition. However, recent research, by Houwelingen [1]“Fleeing Forward: The Departure of Christians from Jerusalem to Pella,” Westminster Theological Journal 65 (2003): 181-200. and others, in my view at least, has shown the tradition is most likely reliable. I have also become convinced that perhaps the Pella tradition referred to the area of Pella, not the city itself. The Wadi Cherith is just six kilometers to the south, literally part of the “precincts” of what could be called Pella. In a matter of minutes it all began to fit together.

I recently discovered that the 4th century Christian Pilgrim Egeria (384 CE) visited Tel Salem, identifying it with the biblical Melchizedek of Genesis 14:18-24. Egeria visited the abundant springs in that area–the “many pools” of John’s Gospel. She was guided by a priest who pointed out to her “This garden is called to this very day ‘The Garden of John’.” She was told that monks of the time come from various places to bathe themselves there. The Israelis call it today “‘Ainot Mechatezetzim,” and the rich springs supply modern fish ponds in the area. Egeria crossed the Jordan and visited Tishbeh, the home of the prophet Elijah, entering a “splendid valley” that she was told was called “Corra,” where Elijah hid from King Ahab and was fed by the ravens. This is clearly the Wadi Cherith that is called “Korrath” (κορραθ) in the LXX, just across from Aenon near Salim (1 Kings 17:3). I find it strangely moving to think of this pious Christian woman “tracking Jesus” in this way over 1600 years ago.

We also have a most interesting passage in the Slavonic version of Josephus’s Jewish War. You can find English translations of some of the principle additions to our Greek version in the Appendix of Vol II of the Loeb Classical Library edition (trans. by H. St. J. Thackeray) based on the work of Robert Eisler. Some scholars have argued that Slavonic Josephus preserves in part the original draft of Josephus’s Jewish War. There is a significant section on one the text calls “John the Forerunner” that contains much of interest. There one reads that John, when opposed by a certain Essene named Simon, “went forth to the other side of the Jordan,” precisely paralleling the language of John 10:40. This reference seems to recall on some level the idea of a “safe” area across the Jordan.

It is in this area, according to the Gospel of John, that a dispute arose between the the disciples of John and “a Jew” over matters of water purification (John 3:25-30). The implication in this context is that Jesus own baptizing activity had somehow sparked the controversy. Water purification was understood in a number of ways among various Jewish groups in late 2nd Temple Judaism. Some restricted ritual immersion strictly to the Torah proscriptions of purification to enter the Temple following menstruation, sexual intercourse, contact with the dead, and various other activities would bring ritual defilement. Others used it as part of a conversion ritual when Gentiles took on the “yoke of the Torah.” Sectarian groups such as those who wrote the Dead Sea Scrolls practiced immersion in water as an initiation rite into their “New Covenant” Community (1QS III.4-12). Josephus comments on this very point in recounting the baptism practiced by John, making clear that his “immersion” rites had nothing to do with the cleansing of the body but only of the soul already purified by repentance (Antiquities 18.117-118).

The Wadi Cherith, across the Jordan, would have been remembered as a “place of safety” for Elijah. Although some have located the Wadi Cherith to the south, the weight of evidence favors the northern Gilead location. It fits the description in 1 Kings 17 precisely, and the site of Jabesh-gilead (Abu el Kharaz) as well as Tishbe has been located in the Wadi. If Jesus also went “across the Jordan,” from Aenon near Salim, that would put him right into the Wadi Cherith, and thus provide an explanation for this odd choice of location for his flight. Finally, nearly 40 years later, his followers, some of whom would have been with him in the winter of 29 CE flight, would have returned to that area.

I had been to Jordan before but only to see the standard tourist sites. I had no idea what the Wadi Cherith might be like. On a modern map of Jordan I saw the name used today: Wadi el-Yabis, which actually connects to the name Cherith (“to cut”), referring to the rugged rock-cut nature of the Wadi. I decided to make a trip to Jordan as soon as the semester was out and in June of that year I found myself hiking with some students and friends deep into the reaches of Wadi el-Yabis.

What we found was quite amazing. The Wadi was incredibly rugged with water falls, pools, and surrounding high cliffs on both sides, dotted with abundant caves. We searched some of the caves and found early Roman period pottery shards in abundance.

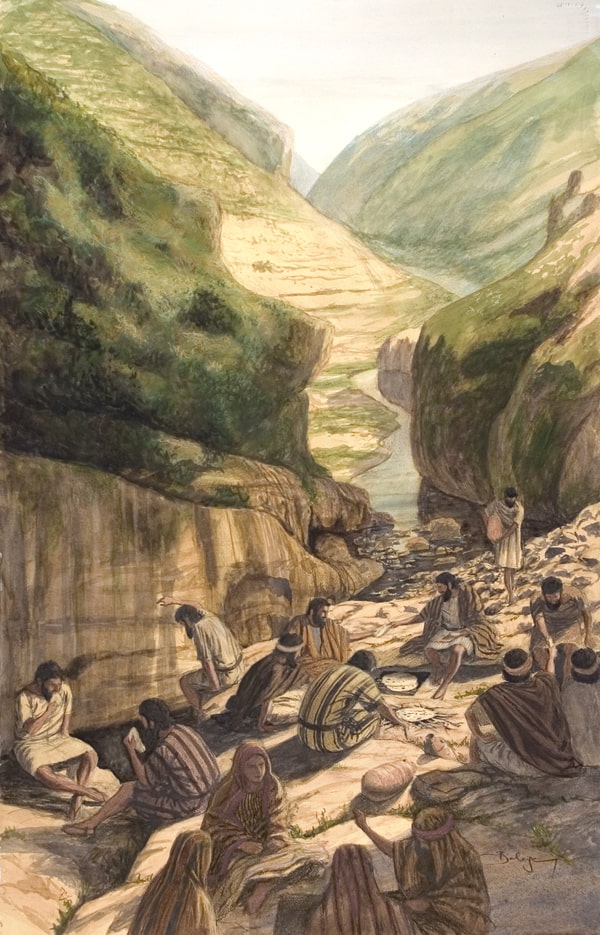

I asked the extraordinarily gifted artist Balage Balogh, who specializes in archaeological drawings and painting, and who was doing illustrations for my book, The Jesus Dynasty, to create a scene that would portray Jesus and his small band of followers living in this Wadi that last winter of Jesus’ life. He took great care in the details, as he always does, wanting to get the clothing, hairstyles, and other things just right. The result, in color, is quite stunning and it helps one to suddenly imagine an amazingly moving scene from the life of Jesus that has never until now been imagined. I have called it “The Last Winter.” I wanted to share it with my readers here:

Based on the traditions of both Mark and John regarding Jesus’ excursion “beyond the Jordan,” as well as the Pella flight tradition, I am convinced that the location of Wadi el-Yabis as a “Jesus Hideout” has good historical probability. If John’s chronology is correct this is where Jesus and his entourage spent the last winter of his life, from December until early April, when he hears of Lazarus being deathly ill and is summoned by Mary and Martha of Bethany to come to the Jerusalem area. It would also be the location where the band of fleeing Nazarenes went in 68 CE as the Roman laid siege to Jerusalem. A Wadi el-Yabis Survey Project (G. Palumbo, J. Mabry, I. Kuijt) begun in the 1990s has identified a number of Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age sites but a specific concentration on potential early Roman habitation of the caves south of Pella remains to be done. I have been back to Wadi-el Yabis four times and we have surveyed the caves and found 1st century CE Roman pottery is quite abundant. Perhaps in the future more work can be done here.

Comments are closed.