Here in two parts, one today, the second tomorrow, I want to offer a broad sketch of how the Biblical hope of “life after death” emerged and developed. Expect some surprises. What few realize, especially those who have focused more on the New Testament, is that the Hebrew Bible had a markedly opposite view of “death and afterlife” than what eventually emerged and triumphed–and not without lots of controversy. These post are very dense with hundreds of biblical textual references and I encourage readers, as I do my own students, to look these up and read them in the Bible.

There is no simple and single response to the question of what the Bible really says about death and life beyond the grave. What one finds is just what one would expect in any book composed of documents from many times, places, circumstances, and authors–variety and development. There are a lot of both, although by “development” I mean here simply change. My treatment presupposes no particular valuation of the various dreams and schemes regarding the future. My approach in this survey will be mainly chronological, tracing the topic through various periods of history; from ancient Israelite down to the Roman period, when the final parts of the New Testament were written. I have also roughly divided the topic into two subtopics: what the Bible says about the future of the world; and what it says about the future of the individual, that is, the afterlife. The two are always interrelated and they often overlap.

THE EARLY HEBREW BIBLE

In the earlier parts of the Old Testament, or Hebrew Bible, one finds fairly uniform views of both the future of the individual human person and that of the world or society. I have in mind here texts and traditions dating from the second millennium B.C.E. down through the time of the Exile of the kingdoms of Israel and Judah by the Assyrians and the Babylonians (8th-6th B.C.E.).

To understand this somewhat singular view of the future one needs to get a general grasp of ancient cosmology. Cosmology is the theory and lore of how the world or universe is structured. A kind of map or picture of the cosmos, cosmology is a way of naming things and putting them in their proper places.

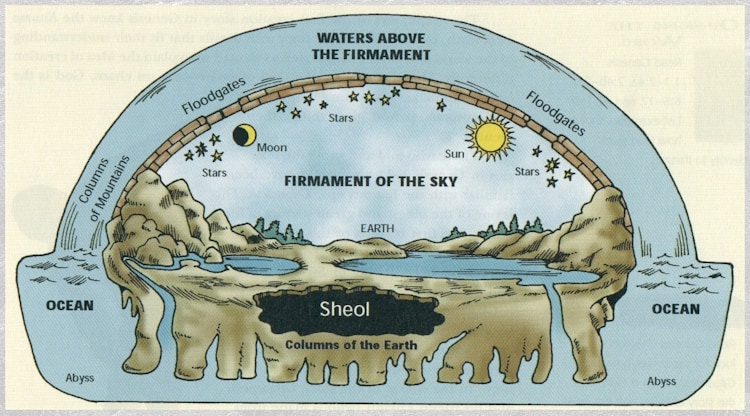

The ancient Hebrews pictured the universe divided into three parts or realms, as did other civilizations of the period. First, there was the upper realm of the Firmament (Sky) or Heavens, the dwelling place of God and his divine angelic court, as well as the place of the sun, moon, planets, and stars. Here no mortal belonged.[1] Then there was the realm of earth below, what the first chapter of Genesis calls “the dry land.” It is the proper human place, shared with all the other forms of plant and animal life–a thoroughly mortal realm. The earth was seen as a flat disk; at the edges were the threatening waters of chaos, held back by the command of God (Gen. 1:9-10; Ps. 104:5-9). Finally, below the earth was the dark realm of the dead, which was called Sheol by the Hebrews and Hades by the Greeks. Psalms 115:16-18 puts it succinctly: “The heavens are Yahweh’s heavens, but the earth he has given to the sons of men. The dead do not praise Yahweh, nor do any that go down into silence. But we [the living] will bless Yahweh from this time forth and for evermore.” [2]

There is a particular set of perceptions, tied closely to this cosmic structure, that has great bearing on the ancient Israelite view of the future. The emphasis on order and proper place is of central importance. Yahweh and the divine beings of his court, whether gods (elohim) of the nations or angels, inhabit the upper heavenly realm and are not subject to death. Such heavenly beings, including Yahweh or his “Angel,” can “come down” to earth and appear to human mortals (see Gen. 11:5-7; 18:20-21; Exod. 3:1-6).[3] Jacob sees in a dream the very “ladder of heaven” with such beings moving up and down between the two realms (Gen. 28:10-17). Yahweh comes down upon Mount Sinai and speaks to the whole vast assembly of Israelites following the Exodus from Egypt (Exod. 19:11, 18; 34:5). Moses and the elders of the nation go up the mountain, meeting him halfway as it were, and encounter him there (Exod. 24:9-11, 15-18). Moses speaks with Yahweh face to face in personal conversation and actually sees his “form” (Exod. 33:11; Num. 12:8). But clearly the immortal beings, or “gods,” belong in heaven–it is their proper sphere, while they only visit the earth below. Conversely, humans are mere mortals, placed on the good earth below, with no idea whatsoever of any “future” in heaven. Their only permanent movement is down, to the lower world of the dead.

Life Beyond the Grave

First I will consider the notion of the future of the individual human person. The ancient Hebrews had no idea of an immortal soul living a full and vital life beyond death, nor of any resurrection or return from death. Human beings, like the beasts of the field, are made of “dust of the earth,” and at death they return to that dust (Gen. 2:7; 3:19). The Hebrew word nephesh, traditionally translated “living soul” but more properly understood as “living creature,” is the same word used for all breathing creatures and refers to nothing immortal. The same holds true for the expression translated as “the breath of life” (see Gen. 1:24; 7:21-22). It is physical, “animal life.” For all practical purposes, death was the end. As Psalm 115:17 says, the dead go down into “silence”; they do not participate, as do the living, in praising God (seen then as the most vital human activity). Psalm 146:4 is like an exact reverse replay of Genesis 2:7: “When his breath departs he returns to his earth; on that very day his thoughts [plans] perish.” Death is a one-way street; there is no return. As Job laments:

But man dies, and is laid low;

man breathes his last, and where is he?

As waters fail from a lake,

and a river wastes away and dries up,

so man lies down and rises not again;

till the heavens are no more he will not awake,

or be aroused out of his sleep. (Job 14:10-12) [4]

All the dead go down to Sheol, and there they lie in sleep together–whether good or evil, rich or poor, slave or free (Job 3:11-19). It is described as a region “dark and deep,” “the Pit,” and “the land of forgetfulness,” cut off from both God and human life above (Pss. 6:5; 88:3-12). Though in some texts Yahweh’s power can reach down to Sheol (Ps. 139:8), the dominant idea is that the dead are abandoned forever. This idea of Sheol is negative in contrast to the world of life and light above, but there is no idea of judgment or of reward and punishment. If one faces extreme circumstances of suffering in the realm of the living above, as did Job, it can even be seen as a welcome relief from pain–see the third chapter of Job. But basically it is a kind of “nothingness,” an existence that is barely existence at all, in which a “shadow” or “shade” of the former self survives (Ps. 88:10).

This rather bleak (or comforting, depending on your point of view) understanding of the future (or non-future) of the individual at death is one that prevails throughout most of the Hebrew Bible. It is found throughout the Pentateuch (the Books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy), and it runs through the books of history, poetry, and prophecy (from Joshua through Malachi) with few exceptions. Those exceptions, however, are noteworthy. The most obvious is the infamous account of the seance in which King Saul has the “witch” (or medium) of Endor conjure up the spirit of the dead prophet Samuel. The narrative is fascinatingly realistic. The medium asks Saul, “Whom shall I bring up for you?” Saul replies, “Bring up Samuel for me” (1 Sam. 28:11). What follows is worth quoting in full:

The king said to her, “Have no fear; what do you see?” And the woman said to Saul, “I see a god (elohim) coming up out of the earth.” He said to her, “What is his appearance?” And she said, “An old man wrapped in a robe.” And Saul knew that it was Samuel, and he bowed with his face to the ground, and did obeisance. Then Samuel said to Saul, “Why have you disturbed me by bringing me up?” (I Sam. 28:13-15). Saul’s intent in trying to contact Samuel was to consult him regarding the wisdom of going into battle against the Philistines. Samuel appears to him in bodily form and gives him a clear prediction of what would befall him, just as he would have done in his prophetic ministry while still alive, he clearly knows the future, even though he has departed below, to Sheol.

Here the dead (at least Samuel) are viewed as “gods” of sorts, resting below in Sheol, but potentially capable of “coming back”–after being “disturbed”–and participating in the life of the living to the extent of even knowing the future. The practice of consulting the spirits of the dead was strictly forbidden in both the Torah and Prophets, but it obviously went on persistently (see Deut. 18:11; Isa. 8:19, 29:4). Throughout this period Israelites apparently thought that the dead could be consulted on behalf of the living. This indicates that their view of the state of the dead in Sheol below was not entirely static. Although generally pictured “at rest,” such spirits could assume special power and still have verbal intercourse with the living world above. Some have also noted as exceptions texts such as Psalms 73:18-26 and 49:13-15, which contrast the fate of the wicked as perishing in Sheol with that of the righteous, who will somehow be “ransomed” from its power. These texts are impossible to date with any certainty, and they might reflect some beginning “hints” of an idea of a resurrection hope for the departed righteous. If so, they probably come from the late Persian period. But even these texts lack a clear affirmation of resurrection of the dead. They might reflect the mere notion of God saving one from Sheol, i.e., rescuing from danger, sickness, and prolonging life. This is clearly the sense of passages like Psalms 22:19-24 and 103:1-5, Isaiah 38:10-20, and Jonah 2:1-9. It is only in certain late portions of the Hebrew Bible, and in sections of the Apocrypha, that we find the beginning expressions of any kind of an actual “future” for the individual beyond death. These will be discussed later in this chapter.

Surprisingly, this view of the future holds true for even the greatest of Israel’s heroes. Genesis 25:7-8 records the death of the greatest of all, Abraham: “These are the days of the years of Abraham’s life, a hundred and seventy-five years. Abraham breathed his last and died in a good old age, an old man and full of years, and was gathered to his people.” The same is said for Moses, David, and all the others (Deut. 32:48-50; 34; 1 Kings 2:10; cf. 2 Sam. 12:22-23). Death is the great equalizer. So, one might accurately say, in ancient Hebrew there is no view of the future for the individual human person, certainly not when contrasted with the later ideas that arose–such as resurrection of the dead or eternal life in heaven. And yet the “religion” of Israel functioned very well without these ideas for more than a thousand years.

The Future of the World

Scholars use the term “eschatology” to refer to what they call the “last things,” i.e., the events and realities at the end of history or, more popularly speaking, “the end of the world.” However, this idea of the “end of the world” does not necessarily mean the destruction of the planet. More often it refers to the end of an “age,” following which history takes a dramatic turn for the better. Eschatology addresses these questions: Where is history headed? And what will be its final determination and meaning? Obviously, one is presupposing here that there is some meaning to history and that the end will make it all clear.

We find little or no eschatology of this sort in the Pentateuch or in the historical books. This is not strictly a matter of chronological development, since before and after the time of the Exile (8th-6th B.C.E.) we do find plenty of material in the Prophets that is clearly “eschatological.” And yet it is around this same time that both the Pentateuch and many of the historical books receive their final edited forms. What we encounter here is fascinating: two very different ways of looking at the future, existing side by side, but in some tension and competition with one another. The first, which is earlier and predominates in the bulk of the Hebrew Bible material, I shall call the “historical.” In this view of things, there is obviously a “future,” since history proceeds on its linear path and generations come and go. But there is no expectation of any dramatic change ahead, i.e., the massive intervention of God through which everything gets set right. The book of Ecclesiastes contains the most systematic and poignant expression of this “non-eschatological’ view of the future. I quote here its opening lines:

Vanity of vanities, says the Preacher,

vanity of vanities! All is vanity.

What does a man gain by all the toil

at which he toils under the sun?

A generation goes, and a generation comes, but the earth remains forever ….

What has been is what will be

and what has been done is what will be done; and there is nothing new under the sun. (1:24, 9)

Obviously, such a view of things, in which there is “nothing new under the sun,” can fill one with a deep sense of despair. After all, the human realm below is full of injustice, suffering, and tragedy, which is what the book of Ecclesiastes is all about. Is there to be no change, ever? The author of Ecclesiastes, like all ancient Hebrews, shares the view that death is the end of all human aspiration and experience, as I described above. He writes:

For the fate of the sons of men and the fate of beasts is the same; as one dies, so dies the other. They all have the same breath, and man has no advantage over the beasts, for all is vanity. All go to one place; all are from the dust, and all turn to dust; again (3:19-20).[5] Surprisingly, this mood of fatalistic resignation and despair, which is expressed so powerfully in Ecclesiastes, does not dominate the Pentateuch and the historical books. By and large, these materials, though sharing at root the same bleak view of the future, reflect another element that tends to make them guardedly, or at least provisionally, optimistic. They are concerned primarily with the future fortunes of the people or nation of Israel, and such a future is seen, potentially at least, as full of abundant good and blessings.

This idea of a good future for the nation of Israel begins with texts in Genesis, which promise such to Abraham and his descendants. God tells Abraham, “I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you, and make your name great, so that you will be a blessing” (Gen. 12:2). Later he is told, “I will make my covenant between me and you, and will multiply you exceedingly.., you will be the father of a multitude of nations” (17:2,4), and “to your descendants I will give this land [i.e., Palestine]” (Gen. 15:18). These elements of “chosen people,” covenant, land, and blessings form the foundation of this view of the future. The twenty-eighth chapter of Deuteronomy best sums up this whole idea. Israel is to be “set high above all the nations of the earth” (Deut. 28:1) and experience incredible material blessings–peace, power, wealth, and health (Deut. 28:3-14), if only she will obey the commandments of Yahweh. However, the bulk of the chapter catalogs in lengthy detail the very reverse of that potential future. If Israel turns from Yahweh, serves other gods, and disregards his commandments, she will experience terrible curses, plagues, and disasters, and finally, near complete destruction, captivity, and exile. This is the basic story line of much of the Hebrew Bible. Yahweh offers Israel all these potential blessings, she consistently rejects him and his laws and suffers various curses, and all the while there is a constant call for her to repent and come back.

I have called this view of the future “historical” rather than properly “eschatological” because it still sees the cosmos (world, universe, history) as a whole, as running along normally with its repeated tale of death, war, disease, suffering, and tragedy. In other words, the lower human realms of earth (history) and Sheol (individual fate) remain fundamentally the same. There is the potential for the chosen people of Israel to experience the blessings of Yahweh, and thus some respite from the brunt of this common human experience. But by and large, for most individual Israelites at most times, the stark view of Ecclesiastes remains the same. Death is the end. There is nothing new under the sun. I should point out that in some few texts there is the notion that the blessings to be poured out upon Israel will “spill over” to other nations (Gen. 12:3). But a more common idea is that such non-Israelite nations will partake of these blessings at a much lower level, as the proverbial “hewers of wood and drawers of water,” that is, as Israel’s slaves (Deut. 20:10-15; Josh. 9:21-27).

NOTES

1. Enoch and Elijah are possible exceptions here. Rather than recording the death of Enoch, the genealogy of Genesis 5:24 simply says, “He was not, for God took him.” Elijah is taken to heaven in a chariot of fire (2 Kings 2).

2. See also Psalm 104 for a celebration of the proper place and created order of Genesis 1. I have generally used the Revised Standard Version translation of the Bible. However, I have rendered the divine personal name of God as “Yahweh” rather than “the LORD.” All emphases within quotations of biblical texts, as well as explanations in brackets, are my own.

3. The “Angel of Yahweh” sometimes appears to be an epiphany of Yahweh himself (Gen. 16:7; 13; 21:17; 19; and Exod. 3:2; 6; 14:i9, 21), sometimes his chief representative (Exod. 23:20-2 1; 33:2-3, 12).

4. The verses that follow (14-15) are sometimes misunderstood as offering some hope of life after death or resurrection from the dead. The context makes clear that the answer to Job’s question, “If a man die, shall he live again?” is no. That is precisely Job’s point.

5. In the next verse he asks, “Who knows whether the spirit of man goes upward and the spirit of the beast goes down to the earth?”–expressing skepticism about such an idea. See 9:3-10; his view is clearly that death is the end.

Comments are closed.