Most of us who work in what we academics call “Christian Origins” hold to the “Two Source” theory of Synoptic Gospel origins. That is, Mark was the earliest narrative gospels, Matthew and Luke both used Mark as their core source, but they had access to another source that we call Q (which is from the German word Quelle–meaning “Source.”), that was a collection of the “Sayings” of Jesus–somewhat along the lines of the Gospel of Thomas–though presumably with more narrative framing. Q is then extracted by isolating the material that Matthew and Luke have in common that is not in Mark. The result is about 50-60 (depending on how one divides topics) units of material, mostly “red letter” sayings of Jesus with a couple of exceptions. For further information about Q, various translations, and lots of analysis see the very useful page at a site called Early Christian Writings: The Contents of Q, with lots of hyperlinks. If you don’t know this web site you will find it quite fascinating to browse on this and other related topics related to ancient texts in the field of “Christian Origins.” Not everyone agrees about Q–notably my friend Mark Goodacre, who has a modified theory, but by and large many of us find it quite plausible–certainly as a working hypothesis.

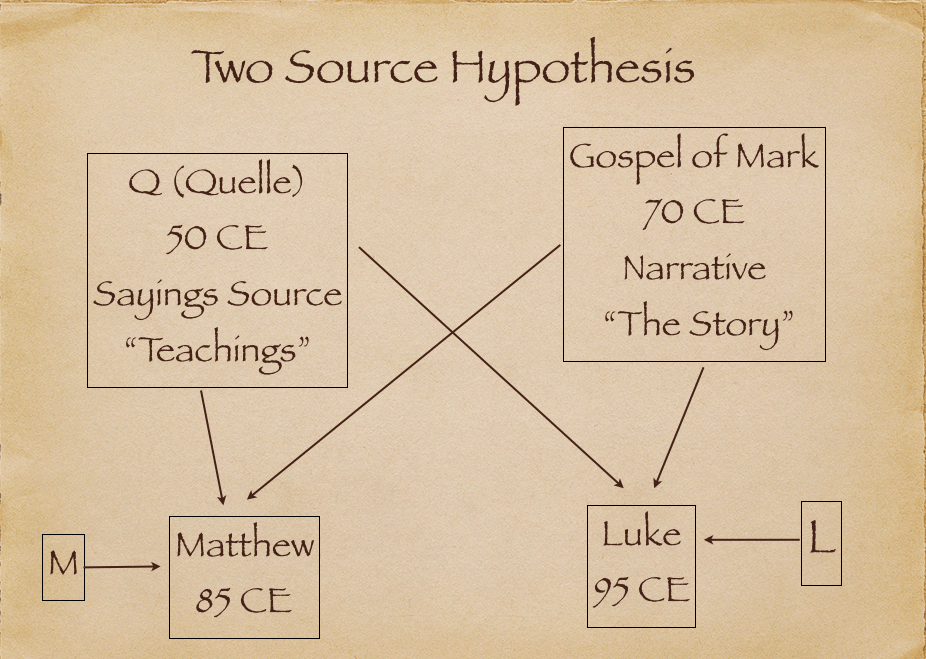

Here is an illustration of how the Two Source theory is constructed:

Markan priority is bedrock for me–having taught comparisons of Mark side by side with Matthew and Luke for over 40 years now. I would go so far as to say both Matthew and Luke are expanded “re-written” Mark. Of course both Matthew and Luke have other materials unique to each–especially Luke–scholars call this material M and L respectively. Each author has characteristic ways of making use of the core narrative source we know as Mark and these methods and editorial tendencies can guide us in imagining how the lost source Q might also have been edited. It is generally agreed that Luke’s version of the Q materials is passed along with less editing than that of Matthew–and one can demonstrate that by comparing the two versions side by side as one works through the 50 or so units of materials. Matthew clearly tends to summarize, shorten, and even recast and smooth out some of the raw sharpness of the version Luke passes on to us. There are many other examples. Luke has

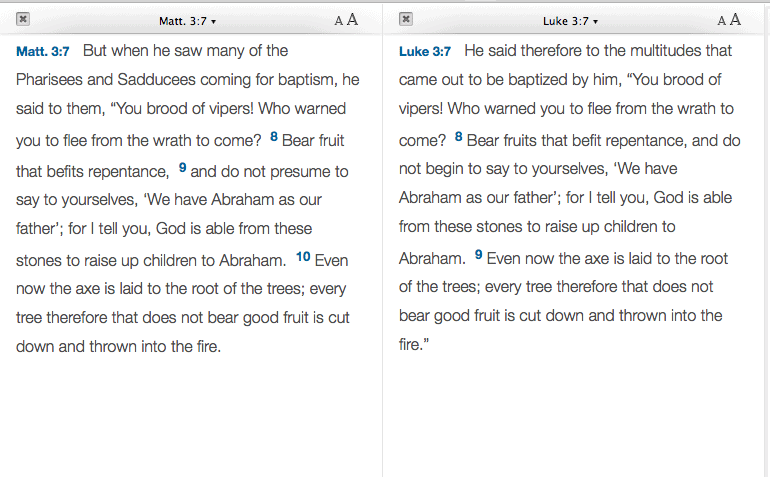

Here is an example of a unit of Q that is rather precisely parallel:

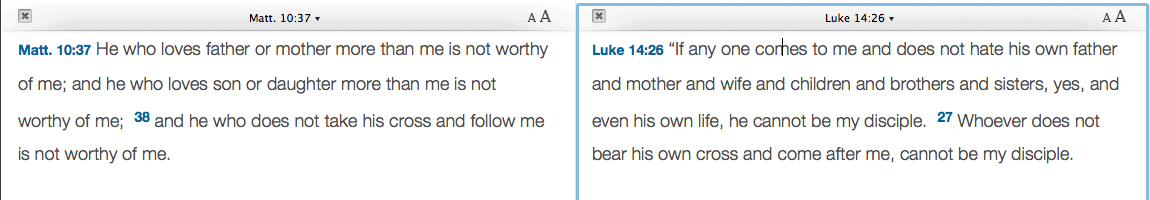

And here is an example where it is very clear that Matthew is “rewriting” or recasting the version we can still see in Luke. It seems more than obvious that Luke preserves something more original. Matthew wants to tone down, interpret, and abbreviate:

And here is an example where it is very clear that Matthew is “rewriting” or recasting the version we can still see in Luke. It seems more than obvious that Luke preserves something more original. Matthew wants to tone down, interpret, and abbreviate:

For those not familiar with Q in terms of its content, here is a convenient link to Luke’s Q material that I compiled using the RSV translation. You you can read through quickly to get an idea of the content and subject matter: Q Source Based on Luke.

You can also find listings of the Q material in various breakdowns at the Early Christian Writings site “The Contents of Q.”

One important caveat in attempting to “extract” Q from Luke or Matthew is that if either of them failed to use any portion of Q then it would not technically be included–but would show up as L or M respectively. We are pretty sure this occurs quite often–where Luke has coherent material that fits with an agreed upon unit of Q, juxtaposed perfectly. All that needed to happen for that to be the case would be for Matthew not to include something Luke did! For example, Luke 3:10-14 has a nice chunk of explicit teachings of John the Baptist, just following the passage above where he denounces the multitudes as a generation of vipers. Matthew does not include this preaching of John. Matthew has an interest in playing down the influence of John the Baptist on Jesus–lest he be seen as more than just a forerunner of Jesus–but maybe his Teacher! This might be a good reason for him to take this material out. Another example: Both Matthew and Luke have versions of the Beatitudes from the Sermon on the Mount–those “Blessings,” upon the poor, the meek, the persecuted, and so forth. However, perfectly aligning with Luke’s four Blessings, he has four Woes–that is condemnations, in precisely the same order. See Luke 6:20-26–concluded with a proverbial statement of Jesus that certainly rings authentic. I think it is highly unlikely that Luke simply composed these condemnatory sayings to parallel the blessings. It is much more likely that Matthew simply did not include them. There are many many other examples.

Some years ago in an advanced graduate seminar at UNC Charlotte, my students and I attended to “recover” or “restore” a more complete version of Q than that extracted by removing just the materials parallel between Matthew and Luke. Our hypothesis was that Q existed and that it was a coherent “Gospel,” not just a string of Sayings of Jesus. Using Luke we attempted to restore Q as closely as might be possible. Each of us–and there were about six in the course–constructed our own version of such a reconstruction. We then critically compared them and here was the result of our composite wisdom and judgment as finally adjudicated by me–I produced this “Final” version.

The yellow highlighted sections are from Luke, but included as likely part of an original Q. Since we have Acts we know very well the “theology” of Luke–as per the late, great, Hans Conzelmann, not to mention Henry J. Cadbury, The Making of Luke-Acts, we are able with some ease to identify materials that are more likely Q than Luke’s own compositions. If something like this was indeed “our earliest Gospel,” perhaps decades before Mark–well, that would be quite something!

I wanted to share it with you here–not for reposting, since this is very much a provisional DRAFT, but you can read through it or print it out and I predict you will be quite “blown away” as the expression goes. This reads and feels, not like Luke (that is Luke as Luke–the author!), but very much like a coherent thematic presentation of “The Gospel,” and it clearly has a light “narrative” flow and a thematic organization.

Enjoy and Imagine!!

Tabor LukeQProject

Comments are closed.