Historically most interpreters of Paul have understood his teaching of “justification by grace through faith” based on the atoning blood of Jesus Christ as his greatest and most central insight. From Augustine to Luther, through Bultmann and Barth, the banner of the “Reformation” was centered on this fundamental precept. Wayne Meeks has a wonderful collection of the classic sources dealing with “Law and Grace” in his masterful volume titled, The Writings of St Paul (Norton Critical Edition, 2nd edition with John T. Fitzgerald added as editor), which should be in every library on Christian Origins. Although I love the expanded 2nd edition but am very sorry the Revised Standard Version translation of the New Testament was dropped in favor of the vastly inferior New International Version which to me is basically useless for studying Paul.

Accordingly, much of the debate among Pauline scholars the past hundred years has been over the question of defining the center of Paul’s theology. I argued in my dissertation on Paul published as Things Unutterable: Paul’s Ascent to Paradise in 1986, and recently in my book, Paul and Jesus, that putting “justification by faith” at the center of Paul’s thought throws everything off balance. Albert Schweitzer’s Mysticism of Paul the Apostler emains the classic study arguing that Paul’s theology develops from his understanding of “being in Christ.” See subsequently, Krister Stendahl, “The Apostle Paul and the Introspective Conscience of the West,” Harvard Theological Review56 (1963): 199-215 and Ernst Käseman, “Justification and Salvation History,” Perspectives on Paul(Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1971), pp. 60-78. E. P. Sanders (Paul and Palestinian Judaism) has provided one of the more persuasive presentations of the case that Paul’s central ideas develop from his experience of being “in Christ” and vice versa (what he calls “participatory” in contrast to “juristic”). With Sanders’ treatment of Paul’s understanding of the Law, righteousness by faith, the human plight, et al., I basically agree, as I do with his notion that we should ask how a religious system as a whole and on its own terms “worked.” However, his description of how a religion is perceived by its adherents to function as “how getting in and staying in are understood,” does not lead one to consider why they wanted in in the first place: Paul’s converts wanted salvation, and yet this is something that Paul rarely stops to define. This salvation involved more than a particular understanding of God’s grace and forgiveness of sins. Sanders’ statement that Paul’s primary conviction is that “Jesus Christ is Lord, that in him God has provided for the salvation of all those who believe . . . , and that he will soon return to bring all things to an end,” is a good general summary, but needs to be more fully laid out.

Paul’s understanding of salvation involves a rather astounding (at least to modern ears) scheme of “mass apotheosis” and imminent cosmic takeover. We must turn to the essential passages which more fully treat the content of this salvation which Paul offered his followers.

In the following posts I survey what I consider to be the six great themesof Paul’s “Gospel.” These form the basis of the exposition I offer in my book, Paul and Jesus. If you find these summaries intriguing be sure and get the book, now out in paperback at a reduced price, for full expositions of each.

1) A New Spiritual Body. For Paul the belief that Jesus had been raised from the dead was a primary and essential component of the Christian faith. He states emphatically: “if Christ has not been raised, then our preaching is in vain and your faith is in vain” (1 Corinthians 15:14). His entire understanding of salvation hinged on what he understood to be a singular cosmic event, namely Jesus’ resurrection from the dead. Paul’s understanding of the resurrection of Jesus, however, is not what is commonly understood today. It had nothing to do with the resuscitation of a corpse. Paul must have assumed that Jesus was peacefully laid to rest in a tomb in Jerusalem according to the Jewish burial customs of the time. He even knows some tradition about that burial, though he offers no details (1 Corinthians 15:4). For a full exposition of this line of thinkings see my post titled “Why People are Confused about the Earliest Christian View of Resurrection of the Dead.”

Paul understood Jesus’ resurrection as the transformation—or to use his words—the metamorphosis, of a flesh-and-blood human being into what he calls a “life-giving spirit” (1 Corinthians 15:45). Such a change involved “putting off” the body like clothing, but not being left “naked,” as in Greek thought, but “putting on” a new spiritual body with the old one left behind (2 Corinthians 5:1-5). So transformed, Jesus was, according to Paul, the first “Adam” of a new genus of Spirit-beings in the universe called “Children of God,” of which many others were to follow.

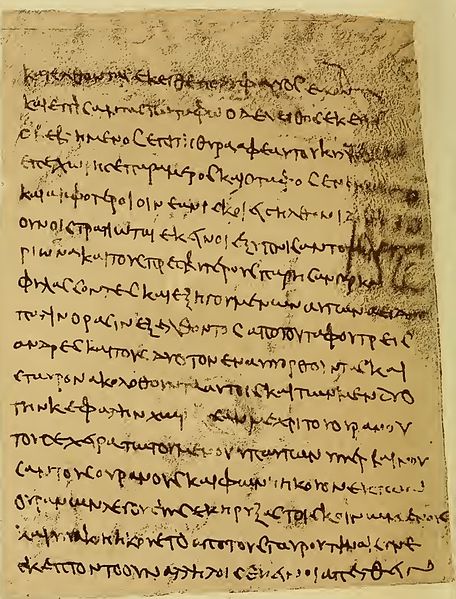

What is often overlooked is that Paul is our earliest witness, chronologically speaking, to claims to have “seen” Jesus after his death. And his is the only first-person claim we have. All the rest are late, and second-hand, and derivative, in contrast to Paul. His letters were written decades earlier than Mark, the first written gospel. This means that Paul’s view of Jesus’ resurrection has profound implications for how we read the later gospel accounts—from the empty tomb to the “sightings” of Jesus reported in Matthew, Luke, and John. Most people read the New Testament “backwards,” chronologically speaking, beginning with the Gospels and then moving on to Paul, but Paul actually comes decades earlier and offers critical insight into what the earliest resurrection faith entailed. Once reexamined, the entire history of what happened “after the cross” is transformed and a new understanding emerges of what James, Peter, and the rest of the original apostles experienced and believed.

2) A Cosmic Family and A Heavenly Kingdom. According to Paul this new genus of Spirit-beings of which Jesus was the “firstborn” is part of an expanded cosmic family (Romans 8:29). Paul believed that Jesus was born of a woman as a flesh and blood human being, descended from the royal lineage of King David, so he could qualify as an “earthly” Messiah in Jewish thinking. But for Paul such physical Davidic lineage was nothing in comparison to the glorification of Jesus as the firstborn Son of God. Paul describes it thus: “The gospel concerning his Son, who was descended from David according to the flesh, but appointed Son of God in power according to the Spirit of holiness through the resurrection of the dead” (Roman 1:4). What this means is that God, as Creator, has inaugurated a process through which he is reproducing himself—literally bringing to birth a “God-Family.” Jesus, now transformed into the heavenly glorified Christ/Messiah, is the firstborn brother of an expanded group of divine offspring. Those who “belong to Christ” or are spiritually “in Christ,” to use Paul’s favorite expressions, have become impregnated by the Holy Spirit and like tiny spiritual embryos are growing and developing into the image of Christ until the time comes for their transformative “birth” from flesh and blood to life-giving Spirits. As Paul says, “He who is joined to the Lord becomes one spirit with him.” Paul compares this union of “spirits” to that of a man and a woman when “the two shall become one flesh” (1 Corinthians 6:17).

The destiny of this cosmic heavenly family is to rule over the entire universe. Everything is to be put under their control, including things visible and invisible. At the center of the message of Jesus was the proclamation that the kingdom of God had drawn near. This kingdom, spoken of by the Hebrew Prophets, was envisioned as an era of peace and justice on earth for all humankind, inaugurated by a Messiah or descendent of the royal lineage of King David ruling over the nations of the world (Jeremiah 33:15; Isaiah 9:6-7). Jesus described it in clear and simple terms in the prayer he taught his disciples: “Let your Kingdom come, let your will be done, on earth as it is in Heaven” (Matthew 6:10). In anticipation of that reign Jesus had chosen the Twelve apostles whom he promised would rule over of the re-gathered twelve tribes of Israel when the Kingdom fully arrived (Matthew 19:28-29; Luke 22:30).

In Paul’s view the kingdom of God would have nothing to do with the righteous reign of a human Messiah on earth, and the status of the Twelve or any other believers was to be determined only by Christ at the judgment. Paul understood the Kingdom as a “cosmic takeover” of the entire universe by the newly born heavenly family—the many glorified Children of God, with Christ, as firstborn, at their head. Paul taught that when Christ returned in the clouds of heaven this new race of Spirit-beings would experience its heavenly transformation, receiving the same inheritance, and thus the same level of power and glory, that Jesus had been given (Romans 8:17; Philippians 3:20-21). This instantaneous “mass apotheosis” would mark the end of the old age that began with Adam, and the beginning of a new creation inaugurated by Christ as a new or second Adam (Romans 8:21). This great event, the most significant in human history, would signal the arrival of the kingdom of God in which nothing flesh and blood could be a part (1 Corinthians 15:50). The group of divinized glorified Spirit-beings would then participate corporately, with Christ, in the judgment of the world, even ruling over the angels (1 Corinthians 6:2-3).

3) A Mystical Union with Christ. Paul completely transformed the practice and understanding of baptism and the Eucharist to his Greek-speaking Gentile converts. Although rituals of water purification were common in Judaism, including the ceremonies of immersion practiced by John the Baptizer and Jesus as a sign of repentance, Paul’s adaptation of baptism moved beyond ceremonial signification. Baptism brought about a mystical union with what Paul called the “spiritual body” of Christ, and was the act through which one received the impregnating Holy Spirit.

Sacred meals involving the blessings of bread and wine were also common in Judaism, and were thus part of the communal meals of the early followers of Jesus. Within apocalyptic groups, such as the Jesus movement and the sect that wrote the Dead Sea Scrolls, such sacred meals were considered anticipatory of the messianic age to come. When the Messiah arrived, his followers expected to gather around his table in fellowship, with Abraham, Moses, and the Prophets joining them. Paul’s innovation, that one was thereby eating and drinking the body and blood of Christ in the form of bread and wine at the Eucharist or Holy Communion, has no parallels in any Jewish sources of the period. Three of our New Testament gospels record Jesus’ Last Supper in which he tells his disciples over bread and wine: “This is my body,” and “This is my blood,” and in the gospel of John Jesus speaks of “eating my flesh” and “drinking my blood.” These writers based their accounts of Jesus’ final meal on Paul, directly quoting what he had written in his letters almost word-for-word (Mark 14:22-25; Matthew 26:26-29; Luke 22:15-20; John 6:52-56; 1 Corinthians 11:23-26). This is one of the strongest indications that the New Testament gospels are essentially Pauline documents, with underlying elements of the earlier Jesus tradition.

As a Jew living in a Jewish culture, Jesus would have considered this sort of language about eating flesh and drinking blood, even taken symbolically, as utterly reprehensible, akin to magic or ritual cannibalism. Despite what Paul asserts, it is extremely improbable that Jesus ever said these words. They are Paul’s own interpretation of the meaning and significance of the Eucharist ceremony that he claims he received from the heavenly Christ by a revelation. For Paul eating bread and drinking wine was no simple memorial meal, but it was quite literally, a “participation” in the spiritual body of the glorified heavenly Christ. This meal connected those who eat and drink through the Spirit with the embryonic nurturing life they needed as developing offspring of God (1 Corinthians 10:16). In contrast, as we will see, there is solid evidence that the Christians before Paul, and outside of his influence, celebrated a Eucharist with an entirely different understanding of the wine and the bread, one that reflects a practice much closer to what Jesus inaugurated at his Last Supper with his disciples. Fortunately, there are fragmented traces of this earlier view embedded in our New Testament gospels.

Comments are closed.