First a bit of personal background. I began my study of New Testament (Koiné) Greek at the tender age of 17 as a young college freshman at what was then called Abilene Christian College (today Abilene Christian University), one of the flagship schools of the Churches of Christ. My family, on both sides, were actively and devotedly part of that wing the Campbell-Stone “Restoration Movement.” That Fall semester of 1963 was memorable for me in so many ways, including studying the New Testament in its original language from the brilliant Robert L. Johnston, and taking my first academic Bible course, the “Exegesis of 1 Thessalonians,” taught by the extraordinary Harvard educated Abraham Malherbe. I still have my first paper, titled “An exegesis of 1 Thessalonians 5:4-6,” in my files, with Malherbe’s markings and the wonderful comment at the end: “Good Paper A.” I can not tell you how much that simple notation–and the grade, meant to me. Malherbe gave a few grades of A- and B’s–but a solid A–that was indeed rare.

That fateful Fall semester President John F. Kennedy was murdered in Dallas on November 22, 1963 as many of you will vividly remember. I was in another Bible class, the “Book of Acts,” taught by Carl Brecheen, when we got the news. Someone knocked on the classroom door around noon that day letting us know the President had been shot. Dr. Brecheen asked us to stand, led us in prayer, and dismissed the class so we could get to the nearest TV or radio. I will never forget that weekend, wandering around campus, saying to one another, over and over, “I just can’t believe it.” We were all in utter shock for days and weeks following as that whole drama unfolded.

As a footnote, years later I read that C.S. Lewis died that same day, November 23, 1963. Also, Yigael Yadin held his first press conference at the Masada excavation that had begun that Fall, of which I knew nothing at the time, and thus began what I have referred to as the “Masada Bones Mysteries, to which I have devoted many years of research and still have not solved. Neither of those events got any attention at all, since by noon in the United States many of us were riveted to Walter Cronkite’s coverage of the assassination and the announcement of his death. If you have never heard it, or vaguely remember it, you can relive the experience here: “Walter Cronkite on the Assassination of John F. Kennedy.”

I had the most wonderful education at ACC, with additional courses from Lemoine Lewis, Everett Ferguson, and Jimmy Jack Roberts, each of whom had Ph.D.s from Harvard. Those were the days. For undergraduate biblical studies that faculty was among the best in the country. Dozens of my classmates went on to get Ph.D.s at major universities and have subsequently had distinguished careers in Biblical Studies. I published my first academic article in the ACC journal, The Restoration Quarterly, titled “The Theology of Redemption in Theophilus of Antioch,” that you can read on-line here.

Based on that first year Greek course, taught by an unsung master of the language, Robert L. Johnston, from whom I subsequently took Classical Greek as well, I decided on Greek as my college major, with a second major in Bible. Almost all the advanced Greek courses were taught by the legendary Paul Southern, and mainly consisted of sitting with Dr. Southern around a table and reading aloud and translating without notes or English versions, from a straight copy of the 2nd edition of Westcott and Hort’s The New Testament in the Original Greek (1896). I still have my well marked fifty-five year old copy! Southern had studied his Greek at the Southern Baptist Theological Seminar with the legendary A. T. Roberston. He would pepper the students with detailed questions of grammar, demanding us to parse verbs from memory or analyze syntax. There was surely a fear for any of us who came unprepared, but also a respect for the ways in which we were forced to truly learn the Greek text of the New Testament.

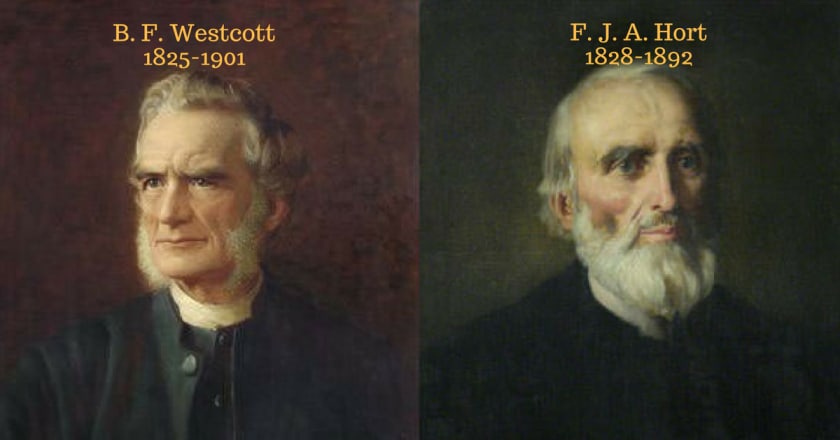

That was my first introduction to B. F. Westcott (1825-1901) and F. J. A. Hort (1828-1892), the towering pioneers of the textual criticism of the Greek New Testament. This involves the ever fascinating critical evaluation of extant manuscript copies of the text, with their variations, interpolations, and differences, in order to determine what is thought to be the most original text, that my friend Bart Ehrman has introduced to the wider world.

Dr. Southern swore by Westcott and Hort, whose work to this day serves as the bedrock of all subsequent critical editions of the Greek New Testament, including the standards of the United Bible Societies used by most scholars and students today (Nestle-Aland, Novum Testamentum Graece and Aland-Black-Metzger-Wikgren, The Greek New Testament-an edition intended more for translators that is less exhaustive in citing textual variants in the manuscripts).

Generally speaking Westcott and Hort favored the Alexandrian text, which they called the “Neutral Text,” namely based on the two main 4th century witnesses, Codex Vaticanus and Codex Sinaiticus. Today, with the addition of the Bodmer Papyri and other even earlier witnesses, that take the Alexandrian type of text to the early 2nd century, the essential judgment of Westcott and Hort seems to be upheld.

In contrast, the more traditional Byzantine text (that Westcott & Hort called the Syrian text), upon which the King James version and most all translations until the 20th century were based, was considered inferior, characterized by numerous additions, interpolations, and theologically motivated changes of what was judged to be the original version.

Westcott & Hort, to this day, draw the ire and condemnation of more conservative Christian believers as “infidels,” who attempted to change the text of God’s word. I just did a Google search “Westcott and Hort” and most of the top Web sites that popped up are devoted to proving that these amazing scholars were basically involved in a “plot from hell” to destroy God’s truth.

One of the most fascinating aspects of Westcott and Hort’s work was their upholding of certain readings from the so-called Western textual tradition, based on manuscripts like Codex Bezae (designated D). Generally scholars are agreed that the Western text is heavily interpolated with loose paraphrasing and lots of traditional and even apocryphal material added. However, at the end of Luke in particular, as well as a few other scattered places, the Western text is strangely shorter than the Neutral/Alexandrian text, with some surprising omissions that Westcott and Hort judged to be closer to the original.

Westcott and Hort identified nine of these passages, which they labeled with the strange designation as “Western non-interpolations,” and they put them as brackets as secondary additions to the original in their edition of the New Testament. I am a great fan of the original Revised Standard Version and to this day prefer it over the New Revised Standard Version (1989), which is the scholarly preference today. The RSV New Testament was published in 1946–the year of my birth. It was roundly condemned as the “Devil’s Bible” and actual book burnings were reported in some circles. The passion and hatred was fueled by any number of features of this impressive new translation but I think the most widespread charge was that the scholars were trying to destroy God’s revelation by a subtle removal of key passages, including the secondary ending of Mark (16:9-20), which was printed in smaller text to mark it as an addition to the original text. In fact, the protest was so great that eventually subsequent printings of the RSV put the text size back to normal and just added a note indicating that these verses were likely secondary to the original.

The RSV also, for the most part, removed and added to footnotes at the bottom of the page, most of the nine “Western non-interpolations” that Westcott and Hort had identified from the Western text:

Matthew 27:49: And another took a spear and pierced his side, and out came water and blood (Although this phrase is not in the KJV it is found in Sinaiticus and Vaticanus, though most judge it to be a latter addition in a clumsy attempt to harmonize with John 19:34).

Luke 22:19b-20: “…which is given for you, Do this in remembrance of me.” And likewise the cup after supper, saying, “This cup which is poured out for you is the new covenant in my blood.”

Luke 24:3: (they did not find the body) of the Lord Jesus

Luke 24:6: he is not here, he is risen

Luke 24:12: But Peter rose and ran to the tomb; stooping and looking in, he saw the linen cloths by themselves; and he went home wondering at what had happened.

Luke 24:36: and said to them, “Peace be to you!”

Luke 24:40: And when he said this, he showed them his hands and his feet

Luke 24:51: and was carried up to heaven

Luke 24: 52: worshiped him, and

When I first encountered this list of passages in brackets in in Dr. Southern’s Greek classes, now over 40 years ago, I was surprised and a bit troubled. I had grown up on the King James Version of the Bible and this introduction to textual criticism of the Greek New Testament came as a bit of a shock to me–much like the experience Bart Ehrman describes in his book, Misquoting Jesus. But it seemed to me, even at the young age of eighteen, that these additions to Luke, not to mention the three interpolated endings of Mark, were clearly secondary additions that the theologically motivated scribes had added to the text over the centuries. The scribe or secondary editor who added the traditional ending of Mark 16:9-20, so beloved to many evangelicals, since it has the “Great Commission,” has in fact just taken the endings of Matthew, Luke, and John and rather woodenly forged them together, with a “glory Halleluja” ending! When I teach Mark in my “Jesus” course I have the students “untangle” these sources as to their derivative origins. It is really not that hard to do. How anyone could read 16:19-20 without sensing this is a much later addition to Mark is beyond me. And it doesn’t stop there, since there is a second “bogus” ending that the RSV puts in footnotes that is really almost comical to read–in terms of anyone taking it seriously as coming from Mark. For more details see my post, “The Strange Ending of Mark and Why it Makes all the Difference.”

It also seemed quite telling to me that with the exception of Mathew 27:49, all of these “Western non-interpolations” were inserted into the last chapters of Luke, and each of them serves to harmonize the text of Luke with that of John and Paul, and thus to reinforce a growing Christian Orthodoxy regarding the Lord’s Supper and Christology in ways that the original text of Luke does not support. I suppose you could say I was a fairly “instant convert” to the view that such readings were secondary. However, at the time it did “rock my world” a bit. Still, I was hooked and I wanted to know more, much more, hence my decision to major in Greek!

Let’s just take the Luke 22:19b-20 interpolation on the words of Jesus at his Last Supper as an example. Since Luke already has a saying about the drinking of the “cup” being a foretaste of the Kingdom of God–but nothing about the body and blood, you can see how that would be a real problem, given Paul’s earlier text in 1 Corinthians 11:23-26. It seems to me more than obvious that these words were added in a rather clumsy attempt (since you end up with two “cups”!) to harmonize things with Luke 22:15-18! See my discussion of this in my book Paul and Jesus, pp. 144-151 and the blog post, “Eat My Body, Drink My Blood–Did Jesus Ever Really Say This?

Interestingly enough, that is far from the end of the story. I was noticing recently that the English Standard Version, that purports to be a kind of Evangelical Christian, but scholarly update of the old RSV, has put all of these verses at the end of Luke back into the text! The late and much beloved, Bruce Metzger, in his A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament (2nd Edition, 1994) notes that a sharp disagreement arose among members of the committee regarding Westcott and Hort’s so-called “Western non-interpolations.” A majority of the scholars were convinced that the traditional longer readings were original and should stay, while a minority maintained that there is such an obvious Christological-theological motivation that accounts for this material having been added they should continue to be footnoted but not included as part of what was considered to be the original Greek version of Luke. Of course the majority prevailed, and translators of a more conservative bent were jubilant that the RSV decision to footnote these interpolations had not been questioned by leading scholars. The issue is such a major one in the eyes of editor Metzger that he includes a special note, at the end of the Gospel of Luke, recounting the committee’s decision (pp. 164-166). Basically the defense rests upon the assertion that the subsequently discovered Bodmer Papyri (particularly the fragment P75), unknown to Westcott and Hort, has allowed us to project the Alexandrian type of text, with these interpolations, back to the second century, so they should no longer be considered late and secondary additions. By and large the “shorter texts” without these additions, as put down to some kind of scribal accident or misunderstanding–which makes no sense at all.

Here I find myself in strange agreement with those “convervatives” who argue that “older is not necessarily better,” in defending the Byzantine textual traditions, the manuscripts of which tend to be much later than the Alexandrian textual tradition. Not that I am any way think the Byzantine text is the closest to the original. What I am saying is that the antiquity of a text, even a late 2nd century text, has nothing to do with such a text being free of such interpolations. This enterprise, of freely “Misquoting Jesus,” apparently begins from day one within our New Testament texts. Notice.

First, from a historical point of view The New Testament text itself in the original, which we do not have, is already a series of interpolations. Matthew and Luke offer their expansions on the core text Mark, quite freely adding, deleting, and rephrasing things at will to carry their own theological agendas. John, as we have it today, is an expansion of the earlier “Signs Source,” and the so-called Deutero-Pauline letter take authentic Paul material and expand, interpolate, and even recast them. Admittedly, this phenomenon makes the enterprise of sorting out the authentic from the inauthentic a more subjective process, but it is in no way without sense or method.

To take an example from the Hebrew Bible, there is no textual evidence whatsoever that indicates that the last verse of Psalm 51, surely one of the most spiritually moving Psalms in the entire Tanakh/O.T. is an interpolation. But any common sense reading of the text would conclude that such is the case, and scholars are fairly agreed that a pious Pro-Temple/Pro-Sacrifice, editor of that Psalm became a bit worried that its implications might prove a threat to the hieratic enterprise. Or to offer another example, in my judgment the last phrase in the saying of Jesus regarding John the Baptizer in Luke 7:28/Matthew 11:11 is an obvious gloss, though there is no Greek textual evidence to support my view:

I tell you among those born of women none is greater than John; yet he who is least in the kingdom of God is greater than he.

I think the same is the case for the Trinitarian baptismal formula at the end of Matthew “in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit” that should stand out to the reader like a sore thumb(Matthew 28:19). Yet all our major Greek manuscripts, early or late, contain these phrases. There is some indication that both Eusebius and Origen knew of texts of Matthew that lacked the baptismal formula, and strangely, the very late 15th century text of Hebrew Matthew preserved by Rabbi Ibn Shaprut in his work Even Bohan, omits the Q gloss about those “least in the kingdom” as well as the baptismal formula. This fascinating text, which George Howard argued was not based on a translation of Greek Matthew, may indeed preserve some earlier stream of textual tradition now largely lost to us.

Recovering the original text of any ancient document requires a number of related approaches, and one is clearly the careful dating of the sequence of manuscript witnesses and variants. But the “older” is surely not the more original, and judgments of content and substance must finally prevail. I remain convinced, after all these years, that my initial judgment that Westcott and Hort’s position on the Western non-interpolations was self-evident remains the case.

Comments are closed.