The investigative task of the ancient historian is by definition an interpretive one and no interpretation is without predisposition or even prejudgment stemming from known or unknown proclivities of both a personal and contextual nature. Add to this the paucity of our incomplete evidence, whether textual or material, and there is no wonder we hardly ever agree on anything of consequence. Nonetheless careful argument based on logical analysis and best evidence remains our only path. [1]James D. Tabor to his students regarding the “methods” of the academy, and more specifically that of the ancient historian.

One of the most frequent responses I get to my work as a historian of religions, particularly in my dealings with Jesus, Paul, and the development of early “Christianities” is the objection that I “exclude the miraculous” as a valid part of the investigation. The idea seems to be that “secular historians” prejudge evidence and are accordingly biased in that they will not allow even the possibility of the miraculous as part of ones historical inquiry. If historians ask the questions: what do we know and how do we know it–how is it that we claim to “know” from the start that miracles do not happen and that supernatural explanations for various developments are to be rejected? As Darrel Bock put things, reviewing my book, The Jesus Dynasty for Christianity Today: “James Tabor’s historical assumptions that reject God’s activity on Earth force him into odd arguments to explain the birth of Christianity.”

For Bock and others these assumptions essentially result in “explaining away the New Testament” to use his words. Bock is referring particularly to my observation that historians assume that all humans have two biological parents, that dead bodies don’t rise, and that humans do not bodily ascend to heaven. Oddly enough, I maintain, along with most historians, that the “odd arguments” are characteristic of those who take the assertions that Jesus had no human father or that he walked out of his tomb and ascended bodily into the clouds of heaven as literal scientific statements of fact. Whether I reject “God’s activity on Earth” is a much more complex matter that I will deal with in another context, but what about this charge that secular historians are biased against the supernatural?

My training at the University of Chicago was that of a historian, not a theologian or even a “Biblical Scholar” as such. My Ph.D. was not from the Divinity School but in the Division of Humanities. I worked broadly in the area study of “Ancient Mediterranean Religions and Culture” and more specifically within ancient Judaism and early Christianity. My teachers were primarily Jonathan Z. Smith and Robert M. Grant. What I reflected in The Jesus Dynasty and in all of my academic work (see my Curriculum Vitae), are the methods and approaches generally employed by most qualified scholars who work in these areas.

Doing the work of an historian is not “hard” science in the purest sense of the term, but none of us in the field would want it to be understood as “art” either, at least not in some wholly subjective way. There is no doubt that historians often differ in their conclusions in important ways, and that “interpretation” of the data, how it is finally weighed and processed, is indeed a somewhat subjective process. When it comes to Jesus, as Albert Schweitzer pointed out long ago, historians all to often have “looked into the long well of history” and seen their own reflection staring back at them. In other words, when they come up with a so-called “historical Jesus” fashioned almost wholly by their own imaginations and biased desires.

When my students retreat to some historical conclusion that I or others have reached, with the easy retort “but that is just your interpretation,” I encourage them to go beyond that kind of reductionism. History is not mere subjective interpretation, even if it involves such. Ideally it is based on arguments and evidence and in the end a good historian wants to be persuasive. It is rare that historical conclusions close out any possible alternative interpretations, but the goal is to set forth, in the open court of reasoned argument and evidence, a compelling “case” for whatever one is dealing with. Even when we disagree we end up stating “why” we don’t find this or that argument convincing, or what we find weak in the assumptions of one with whom we differ.

As for sources, nothing is excluded and everything can be evaluated as long as it offers us some reasonable way to reconstruct the past. Historians love and welcome evidence. That is what we live on and we crave any new materials that can shed more light on what we know. But even our best sources, particularly the literary ones, are remarkably tendentious. Modern standards of argument and objectivity were unknown to ancient writers. Writing was more often than not a blatant attempt at propaganda and apologetics, and all the more so when it came to competing systems of religious understanding. Recognition of those factors is a vital part of every historian’s method. If we want to “use” Josephus we also have to give attention to what we know of him as a person, as a writer, what his tendencies are, what his competence was, and so forth. It is the same with the Gospels, with Eusebius, and with all the ancient texts and material evidence that we have at our disposal. It is also the case that for many important questions related to Jesus and his movement we simply do not have good evidence and probably never will. As thankful as we are for what we have, whether textual or archaeological or myth or tradition, in the end we have to face our own limitations.

Determining what Jesus said, or what he did, given the obvious theologically motivated editing and “mythmaking” that goes on even in our core New Testament gospels is a methodologically challenging project upon which none of us wholly agree. For example, we know virtually nothing about the so-called “lost years of Jesus,” and thus are left to speculate about his childhood and early adult life until about age 30 (assuming we even trust Luke, our single source, about his age when he joined John the Baptizer). Our attempts are educated guesses and creative reconstructions. Most of us are quite sure that the reports of the various so-called “Infancy Gospels” that have Jesus as a child magically turning clay birds into real ones or jumping off the roof of a building unharmed are less than historical. They are late, legendary, and fabulist to the extreme. It is doubtful that such sources contain any useful historical information at all. I cannot prove that Jesus and his brothers worked with their father Joseph in the building trades in nearby Sepphoris, but I think it is a likely possibility, given what we know (see Mark 6:3). In contrast, the assertions that Jesus traveled as a child with his uncle Joseph of Arimathea to Britain, or that he studied in Egypt or in India, are based upon legendary materials far removed in time and place from his world. It is the same with the question of whether or not Jesus was married or had children. For years I agreed with most of my colleagues that the possibilities of this appear to be slight but over the past five years, in looking at the new evidence from the Talpiot tombs, as well as reviewing all the arguments, I have become convinced otherwise. A recent reviewer of our new book, The Jesus Discovery, has asserted on this point that “The claim that the Gnostic Gospels are a good source on Jesus being married to Mary Magdalene, for instance, is just breathtakingly silly — they were written incredibly late and reflect a particular theology/religious perspective–not history.” I have to disagree here and clearly, the reviewer, Raphael Magarik, is completely unaware of the solid scholarship on Mary Magdalene by fine scholars such as the late Jane Schaberg, April DeConick, Karen King, Ann Graham Brock, Margaret Starbird or a host of others. But more important he seems not to have read very carefully the arguments I review in the book that I think are actually quite persuasive.

The public has been geared to think of the suppression of evidence, usually with the Roman Catholic church being the culprit, but such grand “conspiratorial” theories have little basis in fact. What is most characteristic of early Christianity, or more properly, “Christianites,” is a competing diversity of “parties and politics,” each propagating its own vision of the significance of the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. All sorts of interpretations are offered of Jesus, but the question finally comes down to how convincing a given argument is to other historians who work in the field and deal with the same sources and materials. But even “consensus” is no guarantor of final truth. Sometimes a minority view, in time, can prove to be true, and often pioneers in any area of history are castigated or rejected by colleagues when they initially put forth their theses.

Even a subject as seemingly straightforward as the claim in the Gospels that Jesus was raised bodily from the dead and ascended to heaven is one that is “textually bound” by what our sources actually say or don’t say–and the work of the historian is to interpret these texts as objectively as possible. See for example my methods on this very topic in my essay, “How Faith in Jesus’ Resurrection Originated and Developed: An Old New Hypothesis.”

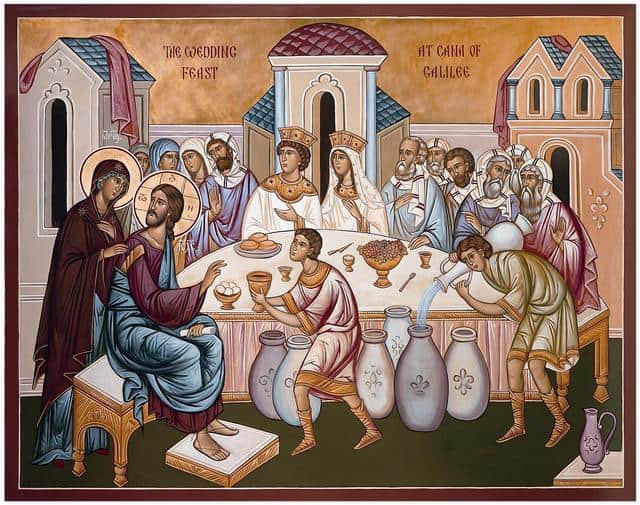

As far as the subjects of the miraculous and the supernatural, historians of religions remain observers. The fact is we do not exclude religious experience in investigating the past–far from it. We actually embrace it most readily. What people believe or claim to have experienced becomes a vital part of our evidence. We can note that Mark reported that Jesus walked on water or raised the dead or met his disciples in Galilee after his death, and then we date and evaluate Mark as a source, just as we note the miracles that Philostratus claims for his contemporary hero Apollonius of Tyana, or that the story that Zeus fathered Hercules or that Romulus was taken bodily into heaven (see these and other texts here). Most scholars in the field would say that Jesus practiced “exorcism,” and healed the sick, which was seen as a releasing one afflicted from Satanic power, but what that implies about the reality of the demonic world goes beyond our historical methods. We know enough about human psychology and our modern controversies regarding psychic phenomenon to realize the complexities of drawing such conclusions. History and theology/faith do part ways in some of these areas but I tell my students often: “Good history is never the enemy of proper faith.” It is easy to hold that “God” can do anything, and thus argue for the acceptance of a male baby being born without male sperm, or reports of a corpse rising after two or three days and ascending bodily into heaven, but such claims are not the purview of historians and they run contrary to our human experience and a more rational scientific understanding of birth and death. Historians likewise deal with “beliefs” about the afterlife and the unseen world beyond, but without asserting the historical reality of these notions or realms. We can evaluate what people claimed, what they believed, what they reported, and that all becomes part of the data, but to then say, “A miracle happened” or this or that “prophet” was truly hearing from God, as opposed to another who was utterly false prophecy, goes beyond our accessible methods. I don’t want to oversimplify things here and I realize that the question of “faith” and “history” and the assumptions modern historians make in terms of a so-called “materialistic” worldview can be challenged, even philosophically. But for the most part historians are willing to leave the “mystery” in, but in terms of advocating this or that view of the so-called “supernatural,” as an explanation, they properly, in my view, remain wary.

We will probably never know with absolute certainty who Jesus’ father was, or what happened to the body of Jesus, or whether Paul “really” talked with Jesus after his death, but I prefer the “odd arguments” of the historian in investigating those matters, however inconclusive and speculative, to the dogmatic assertions of theology that are problematic from a scientific point of view.

Comments are closed.