The festival of Shavuot falls tonight on the Jewish calendar, observed through Monday sundown. Shavuot in Hebrew literally means “weeks” or “sevens,” which refers to the seven weeks between Passover and what was originally a harvest celebration on the 50th day–also called the “feast of firstfruits” (Exodus 34:22). In Greek the festival is known as the feast of Pentecost–which literally means “Fifty” (πεντηκοστή), see Acts 2:1; 20:16; 1 Corinthians 16:8). Christians observe a form of the festival, still called Pentecost, but 50 days after Easter, so no longer connected to the Passover as in the Hebrew tradition.

Shavuot has a long and controversial history. It is probably the least known day of the Jewish calendar to non-Jews, who are culturally familiar with Passover, Rosh HaShanah, Yom Kippur, and Hanukkah. Even many Jews, other than those who regularly attend synagogue, will pay it little mind though it is considered a Sabbath or “rest” day in the Torah (see Lev 23:21).

The controversy has to do with determining the proper date for Shavuot as well as the interpretation of its significance or meaning, which has shifted and evolved through the ages.

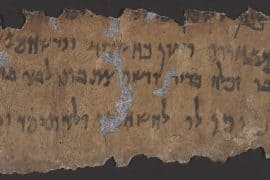

The texts in the Hebrew Bible about Shavuot are few and somewhat obscure, giving rise to some of the controversy. Unlike the other Jewish festivals that fell on a fixed date of the Jewish lunar month (e.g., Passover=15th day of the first month Nisan; Rosh HaShanah=1st day of the seventh month Tishri), there is no date specified for Shavuot or the “feast of weeks.” It had to be literally counted–falling seven weeks plus one day following the offering of the “sheaf of the firstfruits” (called the Omer) which represented the beginning of the grain harvest and was cut from the fields and symbolically “waved before YHVH” for acceptance during Passover week. Thus we read:

You shall count seven full weeks [lit. “sevens”] from the day after the Sabbath, from the day that you brought the sheaf of the wave offering. You shall count fifty days to the day after the seventh Sabbath. Then you shall present a grain offering of new grain to YHVH (Leviticus 23:15-16).

In 2nd Temple times the Sadducees, the Pharisees, and the Essenes each interpreted when to begin this count differently. If the term “Sabbath” was taken here to mean the normal weekly Sabbath, which fell on Saturday, then clearly Shavuot would always fall on a Sunday. But was it to be counted from the Sunday after the Sabbath that fell during Passover week, or from the first Sunday day after the Days of Unleavened Bread (Essenes). However, since the 15th day of Nisan, the first day of unleavened bread, was also understood as a “Sabbath” or rest day, the Pharisees concluded that the offering of the “sheaf of the firstfruits” would always be the day after this “Sabbath,” or Nisan 16th of the lunar month. As a result Shavuot would come 50 days thereafter, and could fall on any day of the week. Ironically, though, with this method a “count” is really not necessary since 50 days after Nisan 16th is always Sivan 6th–that is the 6th day of the 3rd lunar month–so Shavuot ends up having a “date” like all the other Jewish holy days. Nehemia Gordon has a very clear, enlightening, and compelling article on all the details of the issues involved here.

Most Jews today follow the practice of the Pharisees, which was the majority decision of the rabbis of the Mishnah in the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE. The Karaites are the only major group of Judaism, and they are a tiny minority, that still adheres to the Sadducean practice of a Sunday Shavuot. In that sense one might say that Christians, in calculating Pentecost, are closer to the Sadducees, since they adhere to the “always on a Sunday” practice as well. They are joined in this Sunday-Shavuot practice by countless Jewish-oriented Messianic groups, as well as various Sabbatarian Christian, and other Hebraic-oriented groups that are committed to a more literal reading of the biblical texts.

Even more obscure than the “counting” of Shavuot or Pentecost is the question of its meaning or significance. Passover is clearly tied to the Exodus from Egypt, Rosh HaShanah and Yom Kippur to the ancient day of atonement for sins, and Sukkoth or Tabernacles to the 40 years of Israel’s desert wanderings. So what does Shavuot either commemorate or celebrate?

We know it was one of the three pilgrimage festivals at which all males were commanded to go to the “place where God would choose,” which was understood as Jerusalem during the time of the 1st and 2nd Temples:

Three times a year all your males shall appear before the LORD your God at the place that he will choose: at the Feast of Unleavened Bread, at the Feast of Weeks, and at the Feast of Booths. They shall not appear before the LORD empty-handed (Deuteronomy 16:16).

But beyond that we are only told that it had something to do celebrating the beginning of the wheat or barley harvest:

You shall observe the Feast of Weeks, the firstfruits of wheat harvest, and the Feast of Ingathering at the year’s end (Exodus 34:22).

Just as the festival of Sukkoth or “Tabernacles,” here called the “Feast of Ingathering” fell in the early Fall, to celebrate the end of the harvest, the “Feast of Weeks” appears to represent the beginning or inauguration of that harvest.

These kinds of celebrations, tied to the land and its agricultural seasons made sense in their original contexts but for Jews outside the Land of Israel, and subsequently throughout the history of Diaspora Judaism worldwide, not to mention the millions of Christians who also celebrate Pentecost–the original agricultural context of honoring God with the “firstfruits” of the wheat or barley harvest could have little direct application.

What the Jews and the Christians did in the face of this dilemma is quite fascinating. The rabbis noticed that in Exodus 19:1 the Israelites in the time of Moses arrived at Mt Sinai at the third new moon of the lunar year, having left Egypt on the 15th of Nisan–the 1st lunar month (Exodus 12:1). They realized this would work out to approximately seven weeks after Passover, especially since Moses is told that YHVH would descend upon Mt Sinai “on the third day” to deliver the “Ten Words” (literal translation), putting one into the first week of Sivan–the 3rd month of the year. That was close enough to make the claim that the “giving of the Torah” which came during that first week of the 3rd month, was surely on Shavuot–which they were convinced fell on Sivan 6th. This gave rise to the common notion today, so widespread in Judaism, that the celebration of Shavuot has to do with remembering the “giving of the Torah” at Mt Sinai. Observant Jews stay up all night studying the Torah in commemoration of this great event.

The early Jesus movement took another route entirely. They picked up on the biblical notion of the firstfruits of the harvest and offered an allegorical interpretation, alluded to by Paul who makes “Christ” both the sacrificial Passover lamb and the “firstfuit” or “wave sheaf” offering–as the one first raised from the dead (1 Corinthians 5:7; 15:23-24). His resurrection then inaugurates an initial “early harvest” that is gathered when he returns in the clouds of heaven and those who “belong to Christ” are also raised as he was. They will be gathered like ripe fields of grain as the firstfruits of a greater harvest (James 1:18; Revelation 14:4). This could then be taken to imply that subsequently, corresponding to the late fall “festival of Ingathering,” also known as the Feast of Tabernacles or Booths (Sukkoth), there would be another much greater “harvest” involving the mass of humanity. This idea seems hinted at in Revelation 20, where the “rest of the dead did not come to life until the thousand years were finished,” and then are subsequently tested by Satan who is released from his constraint for a limited period–followed by a final “Great White Throne” judgment that involves all of humanity who have ever lived, having been raised from the dead. Paul, offering less detail, but speaking of the resurrection in two stages, declares that “all shall be made alive,” but “each in his own order.” He lists three stages: Jesus raised; those belonging to him raised at his coming; followed by an indeterminate period he calls the “End” or “telos” better translated as the Completion or Perfection, when all enemies, including death itself, is defeated and destroyed and God becomes “everything to everyone” (1 Corinthians 15:20-28).

There are similar “harvest” motifs in the gospels. God is like a master farmer who “when the grain is ripe, puts in the sickle because the harvest has come” (Mark 4:29). Jesus tells his disciples in the Sayings Source that scholars call Q: “The harvest is plentiful, but the laborers are few. Therefore pray earnestly to the Lord of the harvest to send out laborers into his harvest” (Luke 10:2). In the gospel of John, with a direct reference to the agricultural cycles, Jesus says to his disciples, “Do you not say, ‘There are yet four months, then comes the harvest’? Look, I tell you, lift up your eyes, and see that the fields are white for harvest” (John 4:35). When I was growing up in a conservative Christian church there were countless old “Gospel hymns” that we sung from “Bringing in the Sheaves” to “Lord of Harvest,” all tied to this evangelism theme.

Ironically, it is the seven day festival of Unleavened Bread, followed by the feast of Shavuot/Pentecost 50 days later, that in my view offers the key to understanding the narratives regarding the discovery of Jesus’ empty tomb and the traditions of the first visionary “sightings” of Jesus in the Galilee. See my article, “The Last Passover and the First Easter: When Apostles and Angels Wept.”

According to the account in the book of Acts, fifty days following the resurrection of Jesus, which fell on Sunday morning after Passover, takes one to Pentecost or Shavuot–and on that day the followers of Jesus were gathered in Jerusalem and the beginning harvest began with the Holy Spirit being “poured out,” the miracles of “speaking in tongues,” and over 3000 people being baptized as a result of Peter’s preaching that day (Acts 2). So for Christians, Pentecost came to mean the outpouring of the Holy Spirit (thus our term Pentecostal) and the inauguration of the New Covenant of Christ, whereas for Jews it represented the inauguration of the Sinai Covenant.

This mixing of allegory, historical imagination, and theological dogma, superimposed upon what was originally a festival of thanksgiving tied to the agricultural harvest that began in the late Spring of the year is a great illustration of the creativity of religious traditions. Religious ritual and faith tends to abhor any vacuum and in this case the simple words of the Torah: “You shall observe the Feast of Weeks, the firstfruits of wheat harvest,” proved not to be enough for people far removed from an agricultural setting.

Ironically, there is one verse in the Torah that seems to tie this Festival of the Firstfruits or “Feast of Weeks” to a more specific idea and might provide the deepest meaning of all to the festival. It seems oddly out of place, and is generally ignored, but it falls just after the specifications of the festival:

“When you reap the harvest of your land, you shall not reap your field to its very border, nor shall you gather the gleanings after your harvest; you shall leave them for the poor and for the stranger” (Leviticus 23:22).

In our modern age when our food industries have made the seasons and their cycles largely irrelevant, perhaps it bears remembering this day that a simple prayer of thanks “for daily bread” along with remembering the Poor, might be the most appropriate Shavuot/Pentecost observance–with perhaps a glass of good red wine thrown in as well (Psalm 104:15).

Comments are closed.