If one were filling out the some equivalent of a “birth certificate” for Jesus’ the the best legal category within Jewish tradition for his father would be ” Unknown.” [Hebrew “Hushling” שְׁתוּקֵי]

As a historian I work with the obvious assumption that all human beings have fathers. Stated like that, this doesn’t sound too shocking. So, what about the biological father of Jesus? Unless one assumes Jesus had no father, the options seem to come down to either Mary’s husband Joseph or some other named or unnamed male. What can be said of either possibility?

I have spent quite a bit of time investigating the various possible threads of historical evidence that might relate to this question. Perhaps the one most referenced comes from the late 2nd century philosopher Celsus who spins a salacious tale about Mary committing adultery with a Roman soldier named Pantera that he say he heard from the “Jews.”[1] I consider that idea wholly unlikely, although I have tried to trace down what we can say about that name Pantera.

If you ask just about any scholar in my field of Christian Origins you will be told that the expression Jesus the “son of Pantera” was an anti-Christian pun or malapropism, on the Greek word parthenos or “virgin”—and had nothing to do with the name of the reputed biological father of Jesus. Since the Christians were hailing Jesus as “son of the Virgin” (Parthenos), these Jewish and Greco-Roman critics sportingly said he was “son of the Panther”—or so the argument goes. Panthers were known for their sexual prowess, so such a pun was intended to be both humorous and insulting—implying that Jesus’ father was a lusty animal. According to this explanation, Pantera was not even a real name, but just a clever linguistic gibe invented to oppose the Christian claim that Jesus was “son of the Virgin.”

We now know such was not the case. This dismissal of Pantera as a “pun” was first suggested in the 19th century by a German scholar Karl Nitzsch, and his explanation somehow became like a mantra to explain the name and it is repeated by scholars and in popular books alike.[2] Yet, there is not a shred of ancient evidence to support this explanation of the name, even by the harshest enemies of Jesus who used it in accusations that his mother committed adultery. Quite the opposite is the case.

Many readers might be familiar with the numerous tales in Greek and Roman literature about various “divine men”—heroes, philosophers, or demi-gods, whose conceptions were attributed to a god impregnating their mother. The long list includes Hercules with his marvelous feats of strength, Plato and his wisdom, Alexander the Great as conqueror of the known world, and Apollonius of Tyana with his wonder-working powers.[3] These sorts of extraordinary legends are found throughout ancient cultures—whether Greek, Roman, Egyptian, or Hebrew, and their clear purpose is to emphasize the extraordinary significance of the child born. The ancient world did not share our scientific biological understanding of pregnancy and birth. Miracles were part of their everyday lives—and miraculous tales of such conceptions and births were common.[4] These two accounts in Luke and Matthew of Mary’s pregnancy “through the Holy Spirit” can easily be read in this broader cultural context. As such they can be understood less as scientific reports and more as ways of affirming God’s special destiny for Mary’s firstborn son Jesus.

If we begin with our two birth stories—those of Matthew and Luke—both are quite clear that Joseph is not the father. In fact, that seems to be the whole point of both stories. Luke narrates Mary’s side of things, whereas Matthew relates things from Joseph’s viewpoint, but the point is the same. Mary is pregnant “of the Holy Spirit” and Joseph is not the father. Later, when Jesus is an adult, and speaks of God as his father, he is sarcastically attacked by some of his enemies who declare to him, “We were not born of fornication, we have one Father, even God” (John 8:41). They are evidently picking up on the local gossip that Mary’s pregnancy was not from Joseph. They also call Jesus a “Samaritan,” implying his father was of questionable pedigree (John 8:48). The Samaritans claimed to be remnants of the northern tribes of Israel—sometimes referred to as the “Lost Tribes”—who remained in the land after the Assyrian captivity in the eighth-century BCE. They were generally considered by the Jews in the time of Jesus as a mixed race whose ancestry could not be verified. The two charges are thus related—being born illegitimately or born of a Samaritan father with no established pedigree.

Herod the Great had ten wives but one of them, Malthace, was a Samaritan. She was the mother of Herod Antipas and Archelaus, his two most prominent surviving sons whom the emperor Augustus appointed over the Galilee and Judea respectively.[5] We have seen how he and his son Antipas desperately sought some kind of legitimization of their lineages through marriages to women with a priestly pedigree.

Many scholars do not find implications of scandal connected with Jesus’ birth in these texts of Mark and John. Presumably, their assumption is that Joseph was the biological father of Jesus and nothing about the pregnancy was out of the ordinary. In this case the idea that Joseph was not the father was a pure invention of Matthew, followed by Luke, toward the end of the first century; then a hundred years later, Jewish enemies of the Christians came up with the slander that Mary had committed adultery and was driven out by her husband Joseph.

I think this has things completely backward. There is something oddly irregular about Jesus’ birth from the start. Matthew includes four women in his genealogy—Tamar, Rahab, Ruth, and Bathsheba (Matthew 1:3-6) when such male lineages almost never include women. Each of the four is known for some kind of questionable sexual behavior—but all are connected to prominent men connected to the lineage of king David.[6] It as if Matthew wants to hint to the reader—don’t be too quick to judge Mary for her pregnancy, God used these other women connected to the house of David in major ways, despite the irregular nature of their pregnancies. At the same time Matthew makes it clear that Joseph, whose line he is tracing, is the “husband of Mary, of whom [i.e., feminine pronoun in Greek] Jesus was born.” (Matthew 1:16). Likewise, as we have seen, Luke begins his genealogy with the assertion that Jesus was “supposedly” of Joseph (Luke 3:23). That is likely why Mark does not mention Jesus’ birth at all and leaves Joseph completely out of his story. For Mark, Jesus is a Davidic “son of Mary,” and that is all that counts. Although the theologically embellished birth narratives in Matthew and Luke develop a generation after Jesus, they preserve a historical core—Mary becomes pregnant before her marriage to Joseph, Joseph is not the father, so Jesus’ status as a son of David must come from his mother.

The second-century CE Christian writer Tertullian, who is considered the founder of Latin theology, has an interesting passage in which he imagines how Jesus enemies will be punished on the day of judgment for saying he was “the son of a carpenter or the harlot, a Sabbath breaker, a Samaritan and a demon-possessed man . . .”[7] The reference directly echoes the controversy between Jesus and his Jewish opponents in chapters 8 and 9 of John’s gospel, clearly showing that the illegitimacy retort by Jesus’ enemies was based on rumors that his mother was a harlot.

These implications, or outright charges, of illegitimacy are not limited to our New Testament gospels. There is good reason to think this slander might have dogged Jesus and his mother Mary their entire lives. It seems to just pop up, here and there. The Coptic Gospel of Thomas, a text that some date to the early second century, discovered in 1945 among the Nag Hammadi codices, is a collection of 114 sayings of Jesus, most of which are not included in our New Testament gospels. Saying 105 is most interesting:

Jesus said: He who shall know father and mother shall be called the son of a harlot.[8]

This can also be translated as a question: “Will they call him the son of a harlot?” Since these cryptic sayings of Jesus in the Gospel of Thomas have no context, we cannot be certain of their wider meaning, however, the clear implication seems to be that Mary’s pregnancy with Jesus could be seen in in such a negative way.[9] Some have interpreted the saying as referring to the Gnostic notion of despising physical birth—i.e., “hating one’s mother and father”—but in that case one would be more likely called an “orphan” rather than “son of a harlot,” the precise charge that we find is circulating about Jesus’ birth.

The Jewish term for such a child born of any sexual relationship forbidden in the Torah i is mamzer, often mistakenly translated as “bastard,” but it is a legal term, not a term of profanity in Hebrew.[10] It refers to the child born of any sexual union forbidden in the Torah (Deuteronomy 22:13-30; Leviticus 18). This could include incest, adultery, or any forbidden union (Deuteronomy 22:13-30; Leviticus 18). Along with the term mamzer, there was a related term the rabbis use that might be translated a “hushling” or a “silenced one.” This is one who knows his mother but not his father. There is also the term “foundling,” used for one who knows neither father nor mother.[11] The child of a single woman and a man she could lawfully have married is not a mamzer. Also, any child born to a married woman, even if she is known to have been unfaithful, is presumed to be her husband’s, unless she is so promiscuous that such a presumption becomes unsupportable. So much depends on the man. In the case of Mary, we are told that Joseph took her as his wife, which is essentially sanctioning the pregnancy. Such categories are primarily about who can verifiably establish lineage, and who can rightfully marry whom. What we don’t know is to what extent people in fact formed their social groups and boundaries around such distinctions in Mary’s time. As in any age, religious authorities often legislate and make their demands, only to be ignored by both rulers and commoners. We don’t want to make the mistake of reading rabbinic imagination from later centuries back into life in the Galilee in the first century.[12]

The Mishnah, complied in the third-centuryCE, quotes a saying from Rabbi Simeon ben Azzai, an early second-century rabbi, that some take to refer either to Jesus—or if not to him directly, to one of a similarly questionable birth: “I found a family register in Jerusalem and in it was written ‘Such-a-one is a mamzer through [transgression of] your neighbor’s wife’”[13] The use of the term “Such-a-one” to avoid using the name of a controversial person is attested elsewhere.[14] There is an oblique reference in the Babylonian Talmud that I referenced previously, that likely refers to Mary as well, “She who was the descendant of princes and governors played the harlot with carpenters.”[15] The point here, like Tertullian’s association of “son of a carpenter” with Mary being a whore, and possibly Matthew’s altering Mark’s “son of Mary” to “son of the carpenter,” seems to be that someone of high royal pedigree such as Mary consorted with a man of the common working class. This persistent theme, charging Mary with an illicit union, is found dozens of times in various strata of rabbinic sources over a period of several hundred years.[16]

In the fourth-century apocryphal text called the Acts of Pilate, which relates an account of Jesus’ trial before the Roman prefect Pontius Pilate, one of the charges made by Jesus’ enemies echoes the text in John—namely, “you were born of fornication.” No one takes this text as an accurate account of the trial of Jesus; it is wholly legendary, but it shows that the slander persisted over time.[17]

The same idea surfaces in the Qur’an where we read of “a great slander” against Mary, referring to Jesus as “illegitimate,” rather than God “casting into Mary” a spirit causing her pregnancy (4:156, 171; 19:16-36).

I understand even raising this possibility of a father of Jesus is heretical and scandalous. To be clear, Mary was engaged to Joseph according to both our gospel stories (Matthew 1:18; Luke 1:26-27). In Jewish tradition, if an engaged woman has sexual intercourse with a man other than her fiancée, it was considered adultery (Deuteronomy 22:23-24). But there is a fine line between a divinely “engendered” pregnancy and a divinely “sanctioned” one.

So who might Jesus’ father have been—assuming it was not Joseph? Do we have a name or even a hint of such a person? And if so, what do we know about him? As it turns out there is name in some of our ancient Jewish sources—Pantera.

In our earliest examples of the name Jesus is routinely identified as “Yeshua ben Pantera”—Jesus son of Pantera—without any pejorative connotation whatsoever. The name is simply given in passing—a son identified by his father’s name, as common and innocuous as the New Testament designations “Jesus son of Joseph,” or for that matter, “Simon son of Jonah” referring to Peter. These random references come from the close of the first century and the beginning of the second, with stories of rabbis encountering some of Jesus’ followers just a generation removed from him. These references are not focusing on the name “Pantera,” nor do they make any point about it. It is not a very common name, but it is a real name, and it is known even among Jews and non-Jews of the time. What’s more, these earliest stories about Jesus son of Pantera are set in the streets of Sepphoris in the late first century, fewer than four miles northwest of Nazareth. These are local traditions circulating and passed on by those lived in the region. This confluence of time and place is rather extraordinary. I want to examine two of those stories more closely.

The first is a short passing story from the turn of the first century about a certain Rabbi Eleazar ben Dama, who was bitten by a snake. A man named Jacob of Sikhnaya (or Sikhnin) came to heal him “in the name of Yeshua ben Pantera.” Rabbi Ishmael, who heads the Pharisees, objected, since Jesus, or Yeshua, was seen as a heretic by the rabbis. Before Rabbi Ishmael and Rabbi Eleazar ben Dama could finish their debate over the permissibility of such a prayer, Ben Dama died. Rabbi Ishmael attributed the death to giving any credence to a figure like Jesus who had “broken through the fence” of the Torah. We know this expression refers to one who does not accept the Oral Torah and traditions of the Pharisees, which Jesus regularly opposed.[18]

There are three versions of this story. The earliest is in the collection we call the Tosefta (second- to third-century CE), and the latest is in the Babylonian Talmud (fifth-centuryCE). [19] Though similar, the version in the Babylonian Talmud drops the “Jesus son of Pantera” reference and substitutes “Jesus the Nazarene.” This makes perfect sense for a later time, far removed from the Land of Israel, when Christianity had spread widely. Just as important, this further indicates that the name Pantera itself is not the focus of these stories and can come and go in the telling.

The second account with a reference to Pantera is a much longer story, also found in three versions, again including the Tosefta. In this narrative, Rabbi Eliezar, one of the most prominent rabbis of the late first century, was walking on the streets of Sepphoris and met a certain Jacob of Sikhnin.[20] Jacob told him about a teaching of a certain Yeshua ben Panteri—clearly Jesus of Nazareth—as the later version in the Babylonian Talmud makes clear. This teaching from Jesus involved a technical question of Jewish Law: What was to be done with money brought to the house of God that had been earned by a male or female prostitute? Jesus had said it should be received as other gifts, but rather used to build toilets and bath houses, pointing out “from filth it came and to filth it should go,” quoting Micah 1:7. The answer pleased Eliezar very much, and for that Eliezar was arrested on suspicion of sympathizing with heretics, since the teachings of Jesus, however wise or appealing, were anathema to the rabbis at that time.[21]

These two sources are set in the generation after Jesus, in the Galilee, on the streets of Sepphoris, and Jesus is regularly called the “son of Pantera,” with no negative aspersions implied by the use the name Pantera itself. This is our earliest and most important clue in tracking down the possible historical connection of the name Pantera with Jesus. What Jesus son of Pantera is reputed to have taught, in the case of the wages of a prostitute, is good solid halacha—the term used for Jewish legal jurisprudence.

This makes it clear to us that these two Jewish groups—the Pharisees and the Nazarenes—were bitterly opposed to one another, with the former denouncing the latter as heretics. However, they are more what I would call “spitting cousins.” We know that the various sects of Judaism of the late first century were hopelessly divided. In fact, the rabbis say that Jerusalem was destroyed because of the “baseless hatred” within the parties and politics within the Jewish body politic itself.[22]

These earliest references to Pantera stand in the sharpest contrast to several dozen much later references in rabbinic literature that slanderously charged that Jesus was the illegitimate son of a man named Pantera, with whom his mother had committed adultery.[23] And it was this story that then got passed on beyond Jewish circles—including to the philosopher Celsus, who identifies it as a tale passed on by Jews.

Several early Christian writers, responding to these charges that Jesus was the adulterous “son of Pantera,” a Roman soldier, counter with the explanation that the name Pantera was an ancestral name in Jesus’ family lineage, so it would be appropriately used, not as the name of Jesus’ biological father, but as a designation of his general family ancestry. This would be like the way in which the term Hasmonean came to be used for those descended from Asamonaeus or Hasmon—a forebearer of this famous priestly family. Josephus, for example, says of his ancestry, “Moreover, on my mother’s side I am of royal blood; for the posterity of Asamonaeus from whom she sprang, for a very considerable period were kings, as well as high-priests of our nation.”[24] In that general sense, these writers claim, Jesus could be identified as a “son of Pantera.”

Epiphanius, an early fourth-century Christian writer, claims the name is from Joseph’s side of the family.[25] This is of course possible, but less likely than a related claim. John of Damascus, a sixth-centuryCEchurch father, introduces the name into the genealogy of Mary, stating that she was the daughter of Joachim, who was the son of a certain Bar Panther, who was the son of Levi, presumably surnamed Pantera.[26]This is rather remarkable, as it would put the name Pantera into Mary’s royal/priestly line. The sixth-centuryCEJewish Christian author of the Teachings of Jacob quotes a Jewish teacher from Tiberius who claims to know the genealogy of Mary. He writes she is “the daughter of Joakim, and her mother was Anna. Now Joakim is son of Panther, and Panther was brother of Melchi, as the tradition of us Jews in Tiberias has it, of the seed of Nathan, the son of David, of the seed of Judah.”[27] It is difficult to imagine these Greek Christian writers making a place for the name Panthera (or Pantera) in the genealogical records of Mary, Jesus’ mother, unless they had warrant for it in Eastern Christian tradition. It does not surprise me that the name was completely lost in the West and became a mark of slander, since Luke’s genealogy of Mary was usually downplayed in favor of Matthew’s royal line of David through Solomon.

Unfortunately, beyond this idea that Pantera is a name from the families of Mary and Joseph, who might well have been related, we have little to go on.

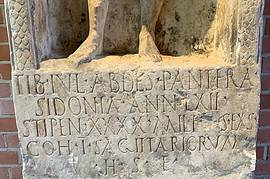

Outside Israel the name Pantera is relatively common as a Roman cognomen or surname, with several examples referring to Roman soldiers.[28] One in particular, noted by Adolf Deissmann in 1910, has caught the attention of several scholars, including Morton Smith, who suggested it might be the only authentic “relic” of the historical Jesus. It is a tombstone monument of a first-century Roman soldier named Pantera near the Roman camp at Bingerbrück on the Rhine River in Germany. Here is the Latin with an English translation:

Tib. Iul. Abdes. Pantera. Tiberius Julius Abdes Pantera

Sidonia. Ann. LXII. of Sidon, aged 62

Stipen. XXXX. Miles. Exs. A soldier of 40 years’ service,

Coh. I. sagittariorum. of the 1st cohort of archers,

h. s. e. lies here

Julius Abdes Pantera was an archer in the Roman army. He was from Sidon, just north of the upper Galilee on the Mediterranean coast of Syria, only sixty miles from Nazareth and he served as a Roman soldier for forty years in the first century CE. He was apparently a slave, freed for his service sometime in the reign of Tiberius (14-37CE)—honoring the emperor by taking on his name. It is possible he might have been Jewish, based on the name Abdes. I have traveled to Germany several times to examine the tombstone and learn what I could about this Julius Abdes Pantera and his career. The tombstone is now in the Römerhalle Museum in Bad Kreuznach not far from the original Roman camp at Bingerbrück. Today there are modern roads and apartments built over the spot. The Roman camp, from what I could tell in consulting with local archaeologists, was nearby on the banks of the Nahe River, which still has foundations of a bridge from Roman times. However, more recent research on the details of Julius Abdes Pantera’s career, has established that this Roman archer Pantera was definitely not a soldier at the time Mary would have become pregnant. Whether he was Jewish, and perhaps taken as a slave into the Roman army, remains a possibility.[29]

The idea that Mary was raped by a Roman soldier has been most ably defended by Jane Schaberg.[30] Needless to say, the backlash on that idea has been massive. The argument she makes is that given the times in which Mary lived, and especially the unrest in the Galilee we have seen following the death of Herod the Great, unless Mary willingly violated her engagement, rape is the most likely scenario with a Roman soldier, perhaps named Pantera, as the father. I see several problems with this possibility. First, our earliest ancient source that identifies Pantera as a Roman soldier is the text from Celsus in the late 2nd century, and he says nothing about rape. Quite the contrary, he asserts that Mary and Pantera choose to be together, despite her engagement to Joseph. Second, at the time of the birth of Jesus, which was nearly two years prior to Herod’s death in March 4 BCE, we know of no disturbances in Galilee that would account for women being raped. Roman soldiers were not stationed in Sepphoris or around Nazareth, but in Syria to the north, under the command of Varus. Herod was in firm control of things around the time Jesus was born.

It should also be noted that in the case of this Pantera of Sidon, he would not have to be in the Roman army at the time Mary became pregnant with Jesus. He might well have either joined or been conscripted into the Roman army after Jesus was born, and thus the rumor circulated that Mary had gotten pregnant from a Roman soldier. Since we have sources that claim that Pantera was a name known in the family of Mary, it is entirely possible that Mary became involved with someone by that name, associated with her extended family, even before her marriage to Joseph was arranged by her parents, whether that Pantera became a Roman soldier subsequently or not.

We can assume that Mary’s parents must have considered Joseph the best match for her—perhaps given his artisan’s trade and some degree of social status. Disagreements over the choice of marriage partners is probably as frequent a topic of contention in families as any other. It is entirely possible that Mary was already involved with Pantera, had become pregnant and kept it to herself, but then when presented with the marriage firmly stood her ground, honoring the child growing within her as a gift of God.

How Joseph comes into the picture we don’t know. Nor do we know whether he was indeed older, or the pick of the family, or whatever, but he appears to be a “good man,” and he can be honored for that. Jesus’ biological father, whoever he might have been, disappears. Whether he was caught up in the massive exile of the upper Galilee after the 4 BCE revolts, or he joined the Roman army, or he met with any number of other possible fates—we will never know.

No one cannot possibly know what Mary might have told Jesus about his father, if she chose to relate to her son the circumstances or exact story of his birth. Jesus might well have grown up under the stigma of being called “son of Mary,” with no father named, as we have seen in our earliest text—the gospel of Mark. Mary may well have stood firm in her choice of his father—no matter what wagging tongues might imply to the contrary and decided to go ahead with her arranged marriage given her circumstances. Only a woman knows the inner secrets of her heart, and with whom and why she decides to share her bed. Maybe Mary believed in destiny. Maybe she raised Jesus with a sense of his specialness, his uniqueness, precisely because she loved his father. We simply have no way of knowing or verifying any of these speculations. But yes, Jesus had a father, as all of us do. And if his name was Pantera, what early evidence we have would make him part of the family clan.

[1] Celsus’s work titled On the True Doctrine, has been lost. What survives is a detailed refutation by the early third-century Christian apologist Origen, titled Against Celsus. In refuting Celsus’s arguments Origen quotes his entire work, paragraph by paragraph—and then adds his responses bit by bit. By collecting all these quotations, and assembling them, scholars have been able to reconstruct Celsus’s original work.

[2] I thank my graduate student Chad Day for first pointing out to me the origin and/or promotion of this idea by Karl Nitzsch, “Über eine Reihe talmudischer und patristischer Täuschungen, welche sich an den mißverstandenen Spottnamen Ben-Pandira geknüpft,” Theologische Studien und Kritiken 13 (1840) 115–20. Joseph Klausner (1874-1958) was a Jewish historian and professor of Hebrew Literature at Hebrew University. In 1922, he published his study of the life of Jesus in Hebrew, Yeshu Ha-Notzri (Jerusalem: Shtibel, 1922). It was translated into English in 1925 as Jesus of Nazareth; His Life, Times, and Teaching, trans. Herbert Danby (London: Allen and Unwin: 1925). Although some scholars doubted the explanation on philological grounds—parthenos and pantera are not closely homophonic—it was repeated endlessly, with no serious investigation, until it achieved the status of a scholarly imprimatur. See, for example, Robert E. Van Voorst, Jesus Outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence (Grand Rapids, Eerdmans, 2000), p. 117. Even John P. Meier, whose research on Jesus tends to be one of the most thorough in terms of evaluating sources, relying upon Klausner, seems to accept this explanation of the “name” Pantera, see A Marginal Jew, pp. 96.

[3]For some samples of such tales see my compilation, “Divine Men, Heroes, and Gods” https://pages.uncc.edu/james-tabor/hellenistic-roman-religion-philosophy/divine-men-heros-gods/ , as well as Charles H. Talbert, “Miraculous Conceptions and Births in Mediterranean Antiquity,” The Historical Jesus in Context, eds. Amy-Jill Levine, Dale C. Allison, and John Dominic Crossan (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006), 79-86.

For comparisons to the kind of tales that develop around Jesus see, Smith, Morton. “Prolegomena to a Discussion of Aretalogies, Divine Men, the Gospels and Jesus.” Journal of Biblical Literature 90, no. 2 (1971): 174-99.

[4] See the insightful summary of ancient evidence, including that of our New Testament Gospels, by Andrew Lincoln, “How Babies Were Made in Jesus’ Time,” The Biblical Archaeology Review 40.6 (Nov/Dec 2014):42-49.

[5] Josephus, Jewish War 1. 562.

[6] Tamar posed as a prostitute and got pregnant by Judah, son of Jacob (Genesis 38); Rahab was the prostitute that aided the Israelite spies in conquering Jericho (Joshua 6); Ruth was a Moabite woman who crawled into bed with Boaz—grandfather of king David (Ruth 3); and Bathsheba, mother of Solomon and Nathan, committed adultery with king David (2 Samuel 11).

[7] Tertullian, De Spectaculis 30. This is my translation of the Latin: “Hic est ille, dicam, fabri aut quaestuariae filius, sabbati destructor, Samarites et daemonium habens.”

[8] Appendix 1 contains a fresh translation of the Gospel of Thomas in William Schneemelcher, ed., Gospels and Related Writings, translated by R. McL. Wilson. Vol. 1 of New Testament Apocrypha. Rev. ed. (Louisville: Westminster/John Knox, 1991), pp. 511-522.

[9] See Funk’s comment, reflecting the majority opinion of the Jesus Seminar Fellows, that this saying has to do with disputes with rival Judean groups over Jesus’ legitimacy, in Robert W. Funk and Roy W. Hover, The Five Gospels: What Did Jesus Really Say? The Search for the Authentic Words of Jesus (New York: HarperOne, 1996), p. 526.

[10] See Bruce Chilton, Rabbi Jesus, (New York: Doubleday, 2000), pp. 5-22 as well as his online article, “The Mamzer Jesus and His Birth” http://www.bibleinterp.com/articles/2005/10/chi298001.shtml.

[11] These categories are laid out in the Mishnah, see Kiddushim 4: Priests, Israelites, impaired priests, converts, freed slaves, mamzers, temple servants (netinim), hushlings, and foundlings. They all have to do with pedigree and lineage—who can marry whom.

[12] For this point I am indebted to the insightful works of Jacob Neusner, my teacher Louis Feldman, and Shaye J. D. Cohen, most particularly.

[13] Yebamot 4:13, s.v. “Jesus” The Jewish Encyclopedia, p. 170 for further comment on this passage. Also, Peter Schäfer, Jesus in the Talmud (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007), pp. 15-24. Tales of Mary’s adultery and Jesus’ illegitimacy run through many later rabbinic texts.

[14] The first-century rabbi, Elisha ben Abuyah, was regularly called “Acher” meaning “the Other,” to avoid using his name. Compare Yoma 66a.

[15] b. Sanhedrin 106a.

[16] See Peter Schäfer, Jesus in the Talmud, pp. 15-24; 97-102 for an analysis of the basic references, but compare Joseph Klausner, Jesus of Nazareth; His Life, Times, and Teaching, trans. Herbert Danby (London: Allen and Unwin: 1925) and Samuel Krauss, Das Leben Jesu Nach Jüdischen Quellen. (1902 rpt. Hildesheim: Olms, 2006).

[17] Acts of Pilate 2.3. See J. K. Elliott, ed., The Apocryphal New Testament: A Collection of Apocryphal Christian Literature in an English Translation Based on M. R. James (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993), pp. 172-173.

[18] On Jesus and the “oral Torah” of the Pharisees, see Mark 7:1-13.

[19] The three versions of this story are: t. Hullin 2.22-23; y. Sabbath. 14d; and b.’Abod. Zar. 27b. The parallel story in y. Sabbath. 14d, involving Rabbi Joshua ben Levi, is immediately adjacent to the Ben Dama account.

[20] James in English = Jacob in Hebrew. It is possible that the name Sikhnin is confused for Shikin, as we know it today, a Jewish village clustered around Sepphoris—just a mile to the northwest. The site is currently being excavated by James Strange from Samford University. Eliezar became one of the greatest rabbis of his time, but he was likely educated as a Pharisee before the horrible days of the destruction of Jerusalem inCE70 and its aftermath, when most of the leading Jerusalem Pharisees fled north to Sepphoris in the Galilee. It is not historically impossible that this Jacob could be “James the brother of Jesus.” The identification with Jesus brother was suggested by Klausner, Jesus of Nazareth, p. 41-42. See the discussion of Richard Bauckham, Jude and the Relatives of Jesus, pp. 106-121. Bauckham does not categorically reject the identification with Jesus’ brother James, though he suggests a more likely choice, chronologically, would be another James, the grandson (or some say son) of Jude, who was the brother of Jesus.

[21] The three texts are: t. Hullin 2:24; Kohelet Rabbah 1:8:3; b.’Abodah Zarah 16b-17a. In this case the later text, from the Babylonian Talmud, also substitutes “Jesus the Nazarene” for “Jesus son of Pantera.”

[22] See Shaye J. D. Cohen, From the Maccabees to the Mishnah, Westminster John Knox Press, 1988 and The Beginnings of Jewishness: Boundaries, Varieties, Uncertainties, University of California Press, 2001.

[23] Peter Schäfer, Jesus in the Talmud is the best study of these later materials. Without claiming they give us accurate historical information, Schäfer shows that such references, even though often cryptic, do in fact refer to Jesus of Nazareth. This is in sharp contrast to Johann Maier, who denies there are any significant references to Jesus in the rabbinic literature, see his magnum opus, Jesus von Nazareth in der talmudischen Überlieferung (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1978). The tradition carries well into the middle ages, with the polemical Jewish treatise known as Toledot Yeshu that exists in many versions, see Krauss, Das Leben Jesu nach jüdischen Quellen, Nachdruck der Ausgabe Berlin 1902 (Hildesheim: G. Olms, 2006), who includes nine different versions of the text. Many of the English translations omit the “seduction scene” as too offensive.

[24] Josephus, Life 1.

[25] Epiphanius, The Panarion, De Fide II and III 78:7-5 through 8:2.

[26] John of Damascus, De Fid. Orthod. iv, 14

[27] Doctrina Jacobi V.16, 209. See Doctrina Jacobi nuper Baptizati, in G. Dagron and V. Déroche, “Juifs et chrétiens dans l’Orient du VIIe siècle,” Travaux et Mémoires 11 (1991) 17-248, that contains an edition of the Greek text with French translation.

[28] Adolf Deissmann, Light from the Ancient East: The New Testament Illustrated by Recently Discovered Texts of the Greco-Roman World, trans. Lionel R. M. Strachen, from the 1922 revised 4th German edition (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1965), pp. 73-75. Deissmann published a more extensive treatment in his 1906 article “Der Name Panthera,” Orientalische Studien T. Nöldeke gewidmet (Brunnen Verlag: Giessen, 1906): 871-875. He gives a half dozen examples of the name Pantera published in Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum—the comprehensive multi-volume collection of Latin inscriptions from the Roman world—including the Bingerbrück tombstone of the Sidonian archer. See also the summary of L. Patterson, “Origin of the Name Pantera,” The Journal of Theological Studies 19, no 73 (October 1917): 79–80.

[29] The best and most recent study is by Christopher B. Zeichmann, “Jesus ‘ben Pantera’: An Epigraphic and Military Historical Note,” Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus 18 (2020): 141-155.

[30] Jane Schaberg, The Illegitimacy of Jesus: A Feminist Theological Interpretation of the Infancy Narratives, Expanded Twentieth Anniversary Edition, (Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press Ltd, 2006). For reactions see her prologue “Feminism Lashes Back: Responses to the Backlash,” pp. 3-10.

Comments are closed.