What about the family tree of Jesus? It is quite a complex question when you begin to look into it.

Matthew calls Jesus a “son of David” in the opening line of his gospel. In Luke the angel predicted to Mary that her son Jesus would “sit on the throne of his father David” (Luke 1:32).[i] The two concepts are intertwined. Not every descendent of David occupied David’s throne, but no one occupied the throne who was not a descendent of David. King David, reputed author of many of the Psalms and father of King Solomon was the most renowned of Israel’s ancient kings. Shortly before his death God promised him that his “throne” would last forever and that only those of his “seed” could occupy it as rulers over the nation of Israel (2 Samuel 7:16). The Hebrew prophets took up this promise and made it the basis for their prediction that in the “Last Days” the Christ or Messiah would sit on David’s throne as an ideal ruler over Israel. He then, of necessity, had to have the right pedigree.

This promise was seen as an unbreakable “covenant.” In the book of Jeremiah God declares that if you can break the fixed order of the heavens “then I will reject the seed of Jacob and David my servant and will not choose one of his seed to rule over the seed of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob (Jeremiah 33:25-26).” This promise to David, of royal descendants reigning over Israel, was likened to a fixed law of nature.

Others might rule the land of Israel, whether Greeks or Romans, but they were regarded as foreign and illegitimate occupiers whom God would rightfully remove when the true Messiah came. There was a brief period of Jewish independence from 163-63 BC, just before the Romans took over the country. A native Jewish family, known as the Maccabees or the Hashmoneans, ruled the country, establishing a priestly dynasty, but unable to claim Davidic lineage.[ii] As we have noted Herod the Great, despite his title “King of the Jews,” feared that true descendant of David’s ancestry might arise and threaten his power.

So one obvious question is how was Jesus a “son of David”? What do we know of his lineage that might support this claim that he was a part of the royal family of David?

Luke and Matthew give Jesus no human father yet they give different genealogical accounts of his ancestry. Genealogies, or what many Bible readers remember as the lists of “begats,” do not usually make gripping reading, but Jesus’ genealogies are full of surprises.

Matthew begins his book with this genealogy: “Abraham begat Isaac, and Isaac begat Jacob, and Jacob begat Joseph,” and so forth. Since Matthew is the first book of the New Testament, more than a few eager Bible readers have had good intentions dampened by this technical beginning. But let’s look again. Matthew lists forty names, all the way from Abraham, who lived a thousand years before David, through David, and down to Joseph, husband of Mary. But there are two surprises.

Any standard Jewish genealogy at the time was based solely on the male lineage, which was of primary importance. One’s father was the significant factor in the cultural world in which Jesus was born. Yet in Matthew we find four women mentioned, connected to four of the forty male names listed. This is completely irregular and unexpected. Luke records:

Judah fathered Perez and Zerah from Tamar (v.3)

Salmon fathered Boaz from Rahab (v. 5)

Boaz fathered Obed from Ruth (v. 5)

David fathered Solomon from Uriah’s wife (v. 5)

These are all women’s names, or in the case of Uriah’s wife, an unnamed woman. But even more surprising, each of these four women was a foreigner who had a scandalous sexual reputation in the Old Testament.[iii] The first, Tamar, a widow desperate for a child, purposely got pregnant by dressing up as a roadside prostitute and enticing her own father-in-law. Rahab was a tavern keeper or “prostitute.” Ruth was a Moabite woman, which was bad enough since Israelites were forbidden to have anything to do with Moabites because of their reputation as sexual temptresses. But Ruth crawled into the bed of Boaz, her future husband, after getting him drunk one night, in order to get him to marry her. Uriah’s wife—her name is not even given here for the disgrace of it all—was the infamous Bathsheba. She had an adulterous affair with King David and ended up pregnant, blending his fame with shame ever after. And yet, Matthew is otherwise giving us the revered royal lineage of King David himself! Something very important is going on here. The regular drumming pattern of a list of male names is jarred by mention of these women, each of whom was well known to Jewish readers. They don’t belong in a formal genealogy of the royal family. The stories of these women in the Bible stand out because of their shocking sexual details. It is clear that Matthew is trying to put Jesus’ own potentially scandalous birth into the context of his forefathers—and foremothers. He is preparing the reader for what is to come.

At the end of the list, the very last name in the very last line, the other shoe drops. Matthew surely intends to startle, catching the reader unawares. He writes:

Jacob fathered Joseph, the husband of Mary;

from her was fathered Jesus called Christ.

What one would expect in any standard male genealogy would be:

Jacob fathered Joseph;

Joseph fathered Jesus, called the Christ.

Matthew uses the verb “fathered” or “begot” (Greek gennao) thirty-nine times in the active voice with a masculine subject. But when he comes to Joseph he makes an important shift. He uses the same verb in the passive voice with a feminine object: from her was fathered Jesus. So a fifth woman unexpectedly slips into the list: Mary herself.

And yet this is definitely not Mary’s bloodline. This is Joseph’s genealogy. So why is she included? Matthew is setting the reader up for the story that immediately follows, in which Mary, an engaged woman, is pregnant by a man who is not her husband. It is as if he is silently cautioning any overly pious or judgmental readers not to jump to conclusions. In the most revered genealogy of that culture, the royal line of King David himself, there are stories of sexual immorality involving both men and women that must be accepted.

But there is yet another remarkable feature of this lineage of Joseph that is vital to the story and should not be missed. Joseph’s branch of David’s family, even though it had supplied all the ancient kings of Judah, had been put under a ban or curse by the prophet Jeremiah. In those last dark days just before the Babylonians destroyed Jerusalem in 586 BC, Jeremiah had made a shocking declaration about Jechoniah, the final reigning king of David’s line: “Write this man down as stripped . . . for none of his seed shall succeed in sitting on the throne of David and ruling in Judah again” (Jeremiah 22:30).[iv] Joseph was a direct descendant of this ill-reputed Jechoniah (Matt 1:11-12).[v]

In effect, it was as if Jeremiah was declaring the covenant that God made with David null and void. At least it might appear that way. Psalm 89, written in the aftermath of these developments, laments: “You have renounced the covenant with your servant; you have defiled his crown in the dust” (Psalm 89:39). Or so it seemed. After all Jechoniah was the last Jewish king of the royal family of David to occupy the throne in the land of Israel. Joseph was of this same line, but as the legal father of Jesus, rather than the biological father, Joseph’s ancestry did not disqualify Jesus’ potential claim to the throne if Jesus could claim descent from David through another branch of the Davidic lineage. But how many “branches” of the Davidic family were there?

Luke’s genealogy provides us with the missing key to understand how Jesus could claim Davidic descent with no biological connection to his adoptive father Joseph. Luke records his genealogy of Jesus in his third chapter. Jesus was 30 years old and had just been baptized by John. Whereas Matthew begins with Abraham and follows the line down to Joseph, Jesus’ adoptive father, Luke begins with Jesus and works backward—all the way back to Adam! Rather than forty names, as in Matthew, we have seventy-six. There are three striking features in this genealogy.

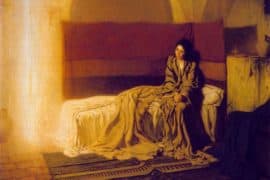

First, it begins with a surprising qualification. Literally translated it says: “And Jesus was about thirty years [old] when he began, being a son as was supposed of Joseph, of Heli (Luke 3:23).” The Greek is quite terse, but what jumps off the page is the phrase “as was supposed.”[vi] Luke is telling his readers two things: that Joseph was only the “supposed” or “legal” father of Jesus and that Jesus had a grandfather named Heli. According to Matthew Joseph’s father was named Jacob. So who was Heli? The most obvious solution is that he was Mary’s father.[vii] One seldom hears anything about the grandparents of Jesus, but Jesus had two grandfathers, one from Joseph and the other from Mary. Two grandfathers mean two separate family trees. What we have in Luke 3:23-38 is the other side of Jesus’ family, traced through his actual bloodline from his mother Mary. The reason Mary is not named is that Luke abides by convention and includes only males in his list. Since Luke acknowledges no biological father for Jesus he begins with Joseph as a “stand-in” but qualifies things with the phrase “as was supposed.” A freely paraphrased translation would go like this: “And Jesus was about thirty years old when he began his work, supposedly being a son of Joseph but actually being of the line of Heli.” If Mary’s parents were indeed named Joachim and Anna, as early Christian tradition holds, it is possible that Heli is short for the name Eliakim, which in turn is a form of the traditional name Joachim.

It is unlikely that Luke simply concocted such a detailed record. Jewish families were quite zealous about genealogical records—all the more so if one was descended from the line of David. Josephus, the Jewish historian of that period, traces his own priestly genealogy with obvious pride and mentions archival records that he had consulted.[viii] Julius Africanus, an early 3nd century Jewish-Christian writer who lived in Palestine reports that leading Jewish families kept private genealogical records, since Herod and his successors had sought to destroy those that were public. Africanus specifically notes the practice of keeping clandestine family genealogies as characteristic of Jesus’ descendants.[ix] Since the Davidic lineage of Jesus was so important to the early Christians it is likely that Luke had one of these records available to him.

Luke’s genealogy also reveals another important bit of information. Mary, like her husband Joseph, was of the lineage of King David—but with a vital difference. Her connection to David was not through the cursed lineage running back through Jechoniah to David’s son Solomon. Rather she could trace herself back through another of David’s sons, namely Nathan, the brother of Solomon (Luke 3:31). Nathan, like Solomon, was a son of David’s favored wife Bathsheba, but Nathan never occupied the throne and his genealogy accordingly became obscure. He is listed in the biblical record but no descendants are mentioned, in contrast to his brother Solomon (2 Chronicles 3:5). So, according to Luke, Jesus could claim a direct ancestry back to King David through his mother Mary as well. He did not have the “adoptive” claim through his legal father Joseph alone, but also that of David’s actual bloodline.

The name Nazareth, the town where Mary lived, comes from the Hebrew word netzer meaning “branch” or “shoot.”[x] One could loosely translate Nazareth as “Branch Town.” But why would a town have such a strange name? As we have seen, in the time of Jesus it was a tiny village. Its claim to fame was not size or economic prominence but something potentially even more significant. In the Dead Sea Scrolls, written before Jesus’ lifetime, we regularly find the future Messiah or King of Israel described as the “branch of David.”[xi] The term is taken from Isaiah 11 where the Messiah of David’s lineage is called a “Branch.” The term stuck. The later followers of Jesus were called Nazarenes or “Branchites.”[xii] The little village of Nazareth very likely got its name, or perhaps its nickname, because it was known as the place that members of the royal family had settled and were concentrated. It is no surprise that both Mary and Joseph lived there, as each represented different “branches” of the “Branch of David.” The gospels mention other “relatives” of the family that lived there (Mark 6:4). It is entirely possible that most of the inhabitants of “Branch Town” were members of the same extended “Branch” family. The family’s affinity for this area of Galilee continued for centuries. North of Sepphoris, about twelve miles from Nazareth, was a town called Kokhaba or “Star Town.” The term “Star,” like “Branch” is a coded term for the Messiah that is also found in the Dead Sea Scrolls.[xiii] Both Nazareth and Kokhaba were noted well into the 2nd century AD as towns in which families related to Jesus, and thus part of the “royal family,” were concentrated.[xiv]

Finally, the names in Luke that run from King David down to Heli, Mary’s father, offer us some very interesting clues that further explain why this particular Davidic line was uniquely important. There are listed no fewer than six instances of the name we know as Matthew: Matthat, Mattathias (twice), Maath, Matthat, and Mattatha. What is striking is that the name Matthew was one invariably associated with a priestly not a kingly or royal lineage. One of Jesus’ twelve apostles was named Matthew, but he was also called Levi.[xv] Two of the six “Matthews” in Jesus’ lineage were sons of fathers named “Levi.” Josephus, the 1st century Jewish historian, records that his own father, grandfather, great-grandfather, and brother were all named Matthias, and they were all priests of the tribe of Levi from the distinguished priestly family of the Hashmoneans or Maccabees. Ancient Israel was divided into twelve tribes, descendents of the twelve sons of Jacob the grandson of Abraham. The priests of Israel had to be descendents of Aaron, brother of Moses, who was from the tribe of Levi. The kings had to be of the royal lineage of King David, who was of the tribe of Judah. These positions, King and Priest, gave the tribes of Judah and Levi special prominence. But why would there be so many priestly names in a Davidic dynasty?

Remember, when Mary became pregnant and left Nazareth to stay with Elizabeth, mother of John the Baptizer, Luke notes that they were relatives, though he does not say how (Luke 1:36). But he also records that Elizabeth and her husband Zechariah were of the priestly lineage (Luke 1:5). This is further confirmation of the link between Mary’s Davidic family and the priestly tribe of Levi.

It is inconceivable that such a heavy prevalence of Levite or priestly names would be part of Mary’s genealogy unless there was a significant influence from the tribe of Levi merging into this particular royal line of the tribe of Judah. What appears likely is that Mary was of mixed lineage. Luke only names the male line from David down to Mary. But the large number of priestly names indicates that there were likely important Levite women marrying into this Davidic line along the way. It is a pattern that goes all the way back to Aaron, brother of Moses, the very first Israelite priest. Aaron of the tribe of Levi married a princess of the tribe of Judah named Elisheva or Elizabeth (Exodus 6:23).

Continue with Part 4 here . . .

[i] Although a few modern scholars have expressed doubt about the historicity of Jesus’ claim to be either a “messiah” or a descent of David, the tradition is early and widespread in all our documents with no one even suggesting otherwise (the earliest texts are Romans 1:3; Mark 10:47; Acts 2:30; 13:23; 15:16; 2 Timothy 2:8; Revelation 5:5; 22:16; Didache 10:6; Ignatius, Ephesians 18:2).

[ii] Josephus says that John Hyrcanus (135-104 BC), though not a descendant of David, declared himself ruler of the nation and high priest—roles ideally intended for two “messiahs,” one priestly and the other Davidic.

[iii] The accounts are found, respectively, in Genesis 38, Joshua 2, Ruth 3 and 2 Samuel 11.

[iv] Jeconiah or “Coniah” is known in the Biblical histories as Jehoiachin (see 2 Kings 17:8-15; 2 Chronicles 36:9-10). He came to the throne at age eighteen and only reigned three months. Nebuchadnezzar carried him away captive to Babylon. He was the grandson of the famous king Josiah.

[v] Jews and Christians of that time were well aware of the problem that Jeremiah’s declaration created for this particular branch of the royal family. Hipppolytus, a 3rd century Christian, even denied that the Jeconiah condemned by Jeremiah was the same one recorded in Matthew’s genealogy. The rabbis, realizing the problem, but revering this royal lineage, speculated that God had later repealed the punishment since Jeconiah had repented in exile—a point not made by the biblical writers (see Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 37b). Eusebius, the 4th century church historian, realizing the serious potential for objections to Jesus’ qualifications as Messiah had he come from this line, suggests that Luke’s genealogy traces his actual bloodline (Quaestiones Evangelicae ad Stephanum 3. 2).

[vi] Greek verb nomizo, refers to what was “thought” or even “assumed.”

[vii] There is in fact a “Mariam daughter of Heli” mentioned in an unflattering way in the Jerusalem Talmud (y. Yerushalmi Hagigah 2:2). The translation of her name is disputed and most scholars agree that this Mary, who is in being punished in Gehenna by being hung by her nipples, has no connection to the mother of Jesus.

[viii] Josephus, Life 1. 6: “Thus have I set down the genealogy of my family as I have found described in the public records, and so bid adieu to those who calumniate me.”

[ix] He is quoted by Eusebius, Church History 1. 7. 13-14. Africanus specifically notes that the members of Jesus’ clan were concentrated in Nazareth and nearby Kokhaba.

[x] The spelling of the name of the town Nazareth from the Hebrew netzer has now been confirmed by a broken marble inscription was found at Caesarea in 1962. It was written in Hebrew and lists the towns where families of priests had settled in the 4th century AD (see M. Avi-Yonah, “A List of Priestly Courses from Caesaria,” Israel Exploration Journal 12 (1962): 137-39).

[xi] For example, 4Q 174, a fragment from Cave 4, quotes 2 Samuel 7:14, the promise made to David and says of the future King, “He is the Branch of David . . . who shall arrive at the end of time.”

[xii] See Acts 24:6 where the term first occurs.

[xiii] See Damascus Document 7:18-21; War Rule (1QM) 11:6-7. This designation for the Messiah was based on a prophecy in Numbers 24:17 about a “star” and a “scepter” arising in Israel. Revelation 22:16 designates Jesus as “the descendent of David, the bright morning star,” clearly linking the two terms.

[xiv] These proud family members called themselves desposynoi which means “belonging to the Master.” Julius Africanus, who lived in Palestine in the early 3rd century, reports that they lived around Nazareth and Kokhaba. There is a another Kokhaba east of the Jordan river that some have identified with Africanus’ statement but it seems much more likely, since he mentions Nazareth as well, that he has in mind the town north of Sepphoris (Eusebius Church History 1. 7. 14).

[xv] Compare Mark 2:14 with Matthew 9:9. Matthew and Levi are the same person.

Comments are closed.