The following is a review of my book, The Jesus Dynasty (Simon & Schuster, 2006), by professor Dennis E. Groh, noted scholar of early Christianity. If you find this very thorough review intriguing I urge those who have not to “read the book” itself, see more information here, and you can “like” it on our new Facebook page here. [1]I personally love the original hardcover edition which is now bargain priced the same as the paperback. It is beautifully bound and even has color plates in the front and back. This study of the “historical Jesus” is a precursor to my new book, Paul and Jesus (Simon & Schuster, 2012), published last November. [2]Dr. Groh received his Ph.D. from Northwestern University, where he spent his career teaching, rising to the rank of Full Professor. After his “first” retirement he took a post as … Continue reading

James D. Tabor, The Jesus Dynasty. The Hidden History of Jesus, His Royal Family, and the Birth of Christianity. NY: Simon & Schuster, 2006. ISBN # 13: 978-0-7432-8723-4

Is there anyone who has been so cut off from the religious scholarship and news reporting of the last decade that s/he does not realize that our portrait of the person and message of Jesus has been seriously “messed with,” if not “messed over” [i.e., intentionally distorted] as it has been transmitted to us in the traditions of both the New Testament and early catholic Christianity? We can now add to the myriad of books offering new pictures of what has come to be called “The Jesus Movement” yet another reinterpretation of its founder and progress.

James D. Tabor of the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, a distinguished scholar of the texts and archaeology of first century Palestinian movements, has written a book that offers a real alternative to historic interpretations of Jesus founded on, and (he thinks) obscured by, the literature of early Gentile Christianity—most notably Paul’s letters and Luke/Acts. In fact, Tabor proposes a different list of literary sources from which he reconstructs a far different picture of Jesus and his movement, one that builds on Jewish prophetic and royal messianic movements:

“The Christianity we know from the Q source, [3]Behind both Matthew and Luke was an oral sayings-collection common to both and unknown to Mark. The German word Quelle (or “Q”) which means “source” was given to this collection of sayings, … Continue reading from the letter of James, from the Didache, and some of our other surviving Jewish-Christian sources, represents a version of the Jesus faith that can actually unite, rather than divide, Jews, Christians, and Muslims, or at least open wide new and fruitful doors of dialogue and understanding among these three great traditions that have in the past considered their views of Jesus to be so sharply contradictory as to close off discussion.” (316).

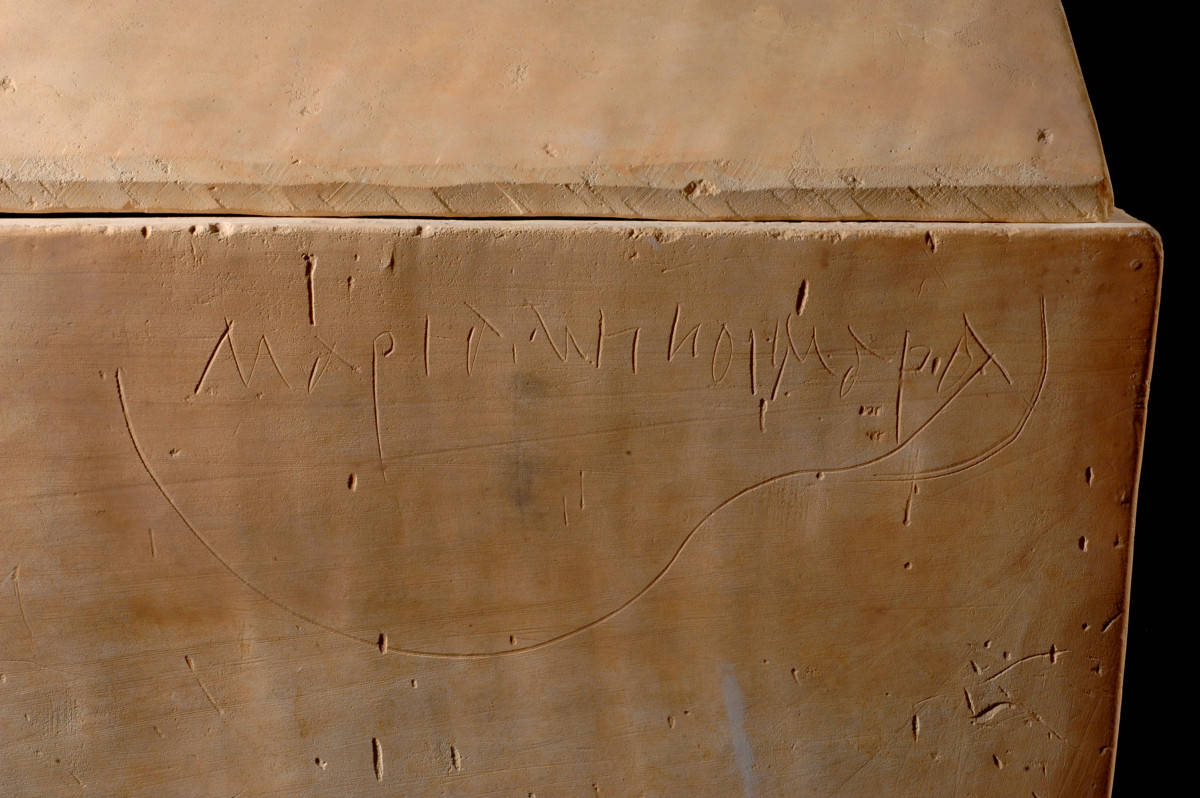

Tabor has utilized recent archaeological finds from first century Jewish ossuaries to stabilize and verify the authenticity of family names attributed to Jesus by the New Testament and other literary remains of the period; he has leaned heavily on the genealogical tables of the Gospels and upon the notices in the New Testament and contemporary literature on the relatives of Jesus; he has drawn on the picture of contemporary Messianic prophecy and scriptural fulfillment from Qumran and the New Testament; he has mined early Christianity for notices of so-called “Jewish Christianity”; and he has accepted as historically accurate many statements from the narrative framework of the Gospels, usually ignored by biblical scholars as purely theological constructs. The picture of Jesus, his expectations, and the successor movement we know as early Christianity departs in a completely different direction from the Christianity long-associated with triumphant Gentile Christianity—that of Paul and Luke/Acts.

Briefly stated, Tabor’s thesis can be summarized as follows:

Jesus was “the firstborn son of a royal family—a descendant of King David of ancient Israel. He really was proclaimed ‘King of the Jews’ and was executed by the Romans for this claim.” (4). Neither a religion-founder or a church-founder, “he established a royal dynasty drawn from his own brothers and immediate family.” (4). The Hebrew Prophets which pointed to a leader from this blood line in the Last Days and the Dead Sea Scrolls gave precision to this expectation that Herod’s house and the Roman rulers worried about and watched-out for. “Shortly before he died, Jesus set up a provisional government with twelve regional officials, one over each of the twelve tribes or districts of Israel, and he left his brother James as the head of this fledgling government. James became the uncontested leader of the early Christian movement. This significant fact of history has been largely forgotten, or as likely, hidden. Properly understood, it changes everything we thought we knew about Jesus. . . . The pivotal place of James, the beloved disciple and younger brother of Jesus, has been effectively blotted from Christian memory.” (4-5).

Not surprisingly, such a radical thesis from so respected a scholar has generated a storm of discussion plus an unusual amount of curiosity in the wider public. The Jesus Dynasty was featured on ABC 20/20 and Nightline, the centerpiece of a cover story by USNews and World Report, and shot immediately upon publication to number 22 on the New York Times best-seller list.

Some key conclusions of Tabor’s—ossuary evidence confirming Jesus’ familial names (including accepting the authenticity of the disputed “James Ossuary”); his assertion that Jesus’ brothers and sisters were children of Mary by a second marriage (likely to Clopas or Alphaeus, the brother of Joseph); the location of Jesus’ probable permanent burial [hence, Tabor’s denying any resurrection claims], along with that of James, somewhere near the Mount of Olives where he thinks Jesus was actually crucified—really push the boundaries of the evidence to its extremities. And his case is not helped by “what if” thinking that he reports from various historic locations he visits in ancient Palestine. But despite its radical ragged-edges and popularist speculations, this book makes a major contribution to a new picture of Jesus which takes into account very crucial and completely disregarded aspects of early Christianity. I want to take you on a sampling of three “soundings” into Tabor’s research that show how truly interesting and controversial his work is.

1. Jesus Relationship to John the Baptizer. One of the clearest embarrassments of the written Gospels is the priority in time and importance of John the Baptizer. John not only began the “Kingdom” preaching first; it was John who baptized Jesus, not the other way around. The writers of the four Gospels respond by stressing the clear superiority of Jesus to John, emphasizing that he was only a forerunner of or witness to Jesus’ messianic status (cf. 136-137). ). Here, Tabor turns to the Q document’s saying in Luke 7:26, that there is “no one greater than John,” which Luke or the early Christians amended to, “yet the least in the kingdom is greater than he” (136). Clearly, Jesus had considered John an equal in the original form of the saying. Another Q saying preserved in Luke 7:32-34 (which Tabor does not cite) underscores the contention that early in his ministry, Jesus considered John and him to be equal partners in announcing the news of the Kingdom. Thus when Jesus’ disciples ask to be given a prayer, as were the disciples of John, Tabor suggests the Lord’s Prayer Jesus taught his disciples was the very one he himself learned from John (137).

In Tabor’s complicated and intriguing reconstruction, early in his ministry Jesus moved south into Judea baptizing while John remained baptizing in the north—at the crossroads of Herod’s territory, the Galilean routes south, and the safety of western Transjordan (that is, out of what he supposed was the “reach” of Herod Antipas). Drawing on the Qumran literature, Tabor argues for a joint message to Israel delivered in concert by the Priest Messiah (John the Baptizer) and a Davidic Royal Messiah (Jesus) (pp. 147-150).

“Later, after Jesus’ death, when a replacement on the Council of Twelve was chosen for Judas Iscariot. . .it was specified that only candidates who had been with Jesus and the group ‘beginning from the baptism of John’ would be considered for this important office (Acts 1:22). Christians later tended to separate the two movements—that of John the Baptizer and Jesus, as if one was ‘Jewish’ and the other ‘Christian.’ In the lifetime of Jesus, and among his immediate followers, there was one unified movement and one baptism.” (150). It is only with the shocking and sudden arrest and killing of John, that Jesus realizes he must go on alone proclaiming: “the time is fulfilled and the Kingdom of God is at hand.” (157).

2. Jesus’ Genealogy and Family. While most scholars skirt the genealogies of Jesus that open Matthew and Luke, Tabor mines them for the strange inclusions that appear there. He treats the information as historical data and not just as the Gospel writers’ inventions of interwoven quotations from the Septuagint [i.e., the Greek translation of Hebrew Scripture cited in the New Testament]. These genealogies provide Tabor with important clues to Jesus dynastic claims. Noting that especially Luke includes the names of women associated with the Leviticus (Priestly) tradition, he argues that Mary possess both the Davidic and Priestly lines of descent which she passes on to Jesus (56). In fact, Mary has both the royal and priestly lines one expects in an “anointed king” [a priestly king; cf. Aaron, actually the first ‘Messiah’ in the bible: Exodus. 40:12-15]. (56). The Talpiot family tomb-find (near Jerusalem) shows another first century example of the family association brought about through the intermarriage of individuals descended from both Priestly and Davidic lines (51-56).

Most importantly to Tabor is the fact that all four Gospels avoid claiming paternity for Joseph, thus clearing the way for him to argue for an unknown (human) father for Jesus and a second marriage for Mary (61-62), producing the four brothers and two sisters of Jesus that Mark 6:3 mentions (73).

It is on his biological family that Jesus builds his dynastic hopes: “Jesus by age thirty functions as head of the household and forges a vital role for his brothers, who succeed him in establishing a Messianic Dynasty destined to change the world. This extended family of Jesus is the foundation of the mostly forgotten and marginalized Jesus dynasty and it is long overdue for resurrection. By restoring the various historical possibilities related to the family, we are prepared to gain a truer understanding of Jesus and how he might have understood what he believed was his God-ordained mission as Messiah and King of a restored nation of Israel.” (81).

3. The Leadership of the Jerusalem Church. Despite efforts to skip over, or minimize, the fact, when the curtain opens after Jesus death, James leads the The Twelve. The leadership of the early New Testament church has passed to Jesus brothers, especially James.

“This is perhaps the best-kept secret in the entire New Testament: Jesus’ own brothers were among the so-called Twelve Apostles.” (165).

Everyone assumes that Jesus brothers never believed in him. “This spurious opinion is based on a single phrase in John 7:5 that many scholars consider to be a late interpolation. Modern translation even put it in parentheses.” (165). James, in fact, is not only a disciple; he is the beloved disciple (165).

Thus, the latter part of Tabor’s book is spent carefully introducing the kind of Christianity that was dominant in the succession of Jesus relatives [note: not Peter] as heads of their church (until 106 CE) (291-293), whose movement continued to exist into the fourth century CE. The theology of this earliest movement existed in sharp contradistinction to the Pauline views of the heavenly, divine Christ whose Gospel abrogated the Jewish Law. For the Jesus Movement, who saw themselves as “faithful Jews” (not “Christians,” and certainly not “Jewish Christians”), no abrogation of the Law, no matter how widely the good news was to be proclaimed, was ever conceived (266). Paul’s insistence that the Law was a temporary or custodial guardian until Christ or a “temporary revelation” and his bitter polemic against Jewish observance was totally different from the Messianic Movement’s proclamation and aims (cf. 267).

I have only scratched the surface of this book in the three soundings above; but I encourage you to read it for yourselves. Because Tabor is constructing a new thesis on all kinds of evidence, a number of his statements are educated “guesses” and speculation to be tested by future information and study (cf. his discussion of DNA evidence, pp 11-12, 14, 22). Many who read this book will be outraged by his arguments and conclusions. But, from my point of view, a thesis rarely flies into my scholarly life out of nowhere that makes me rethink my entire scholarly framework; and The Jesus Dynasty is certainly one of those very rare birds.

For contemporary “children of Abraham,” by emphasizing the human, prophetic, ethical and messianic center of the Jesus Movement, Tabor has put interfaith dialogue on an entirely different basis. He has set the very matrix and foundation of early Christianity back into a world comprehensible in terms of both ancient Judaism and the rise of Islam.

Comments are closed.