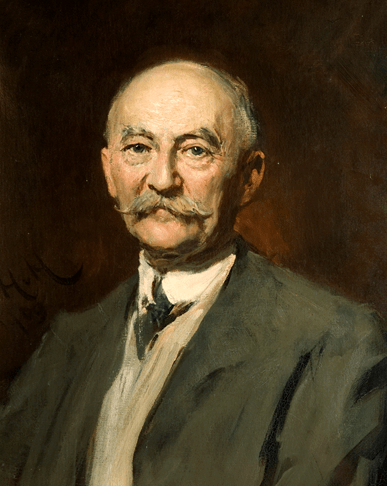

For years I have considered Thomas Hardy (1840-1928) one of the most moving, informative, and influential novelists of my own reading experience. I remember first reading Tess of the d’Urbervilles and Jude the Obscure over 30 years ago and the images and power of those tragically realistic portrayals of human life on planet earth still remain with me today.

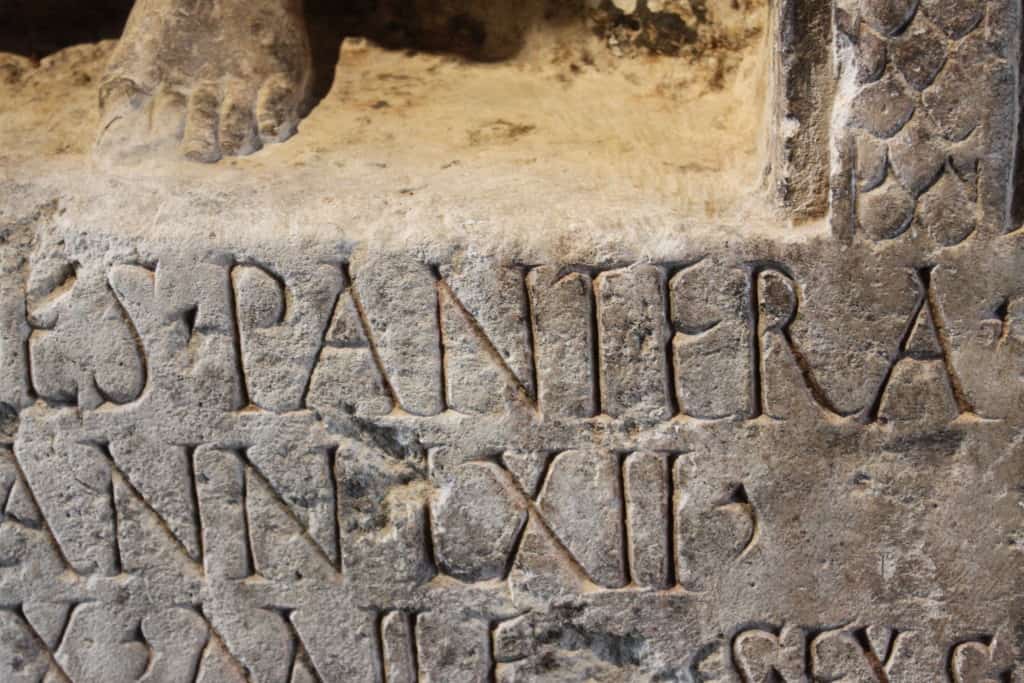

What I have only learned recently is that Hardy gave up writing novels after completing Jude the Obscure in 1895, and largely spent the remainder of his literary career writing poetry. Hardy published his first volume of poetry, Wessex Poems, in 1898. In 1909 he published another volume titled Time’s Laughingstocks and Other Verses. This volume contains a long and passionately rendered poem called “Panthera.” Hardy apparently began to think deeply about the Panthera story as related by the pagan philosopher Celsus as well as in other ancient Jewish sources–namely that the biological father of Jesus was a young Jewish man who later served in the Roman army. I am also convinced that Hardy was aware of the revelation, in 1906, by Adolf Deissmann, of the Panthera tombstone in Germany (see my Jesus Dynasty, pp. 65). The entire tale fired his romantic and melancholy heart.

This largely forgotten poem is amazingly executed in perfect iambic pentameter and rhymed mostly in couplets. Literary critics have found in it much to admire and evaluate in terms of its contributions to form and genre (see Renner’s lovely analysis). It chronicles the sexual and romantic love between a teenaged Mary and a Roman soldier Panthera, stationed in Palestine, but narrated from the point of view of the aging Panthera, thinking back on his life and what he has left behind. The lines are memorial and I urge readers to find the entire poem and read it themselves in the closest good library. Among those that jumped out at me:

A son may be a comfort or a curse,

A seer, a doer, a coward, a fool; yea worse…

Pantera recalls how he had first met Mary at a stopover in Nazareth, at the town spring, with touching imagery:

I proffered help to one–a slim girl, coy

Even as a fawn, meek, and as innocent.

Her long blue gown, the string of silver coins

That hung down by her banded beautiful hair,

Symboled in full immaculate modesty.

He was thoroughly taken in by her goodness and her innocence, what he calls “The tremulous tender charm of trustfulness.”

We met, and met, and under the winking stars

That passed which people earth–true union, yea

to the pure eye of her simplicity.

He leaves the country, only to return 30 years later at Jesus’ death, where he sees Mary at the crucifixion and he learns:

Though I betrayed some qualm, she marked me not;

And I was scare of mood to comrade her

And close the silence of so wide a time

To claim a malefactor as my son–

(For so I guess him). And inquiry made

Brought rumour how at Nazareth long before

And old man wedded her for pity’s sake

On finding she had grown pregnant, none knew how,

Cared for her child, and loved her till he died.

He never sees her again but a near the end Pantera offers sage advice to all who might hear:

Now glares my moody meaning on you, friend?-

That when you talk of offspring as sheer joy

So trustingly you blink contingencies,

Fors Fortuna! He who goes fathering

Gives frightful hostages to hazardry!

Hardy’s poem can surely be seen against the backdrop of his general aversion to conventional forms of religious authority and Christian tradition. However, I think it is likely more than that. He finds in the Pantera story a most apt expression of the most touching aspects of a universal humanness. Human love, separation, the uncharted life of a child, and all they might mean to one old and thinking back on it all. And who could better portray the “human all-too-human,” than the enshrined Mary, mother of God and her divine Son Jesus Christ of Nazareth. It is not just that Hardy disbelieved such orthodoxies, but more that he wanted these figures, the chief symbols of all that is heavenly and perfect and removed from our world, to end up serving that very thing–our very human existence on this planet, so fraught with uncertainties, foolishness, hope, and finally death.

Although I do not share all the details of Hardy’s vision, I do indeed find the Panthera poem profoundly moving for its human sentiments. I have to wonder if James Whitehead might have been influenced by Hardy’s work, though he surely forges his own imaginative account of things in his poems on “The Panther.” I anxiously await the time when the Whitehead corpus will be published and available for all to read. It is truly a legacy worth passing on by a great and gifted mind and heart.

Comments are closed.